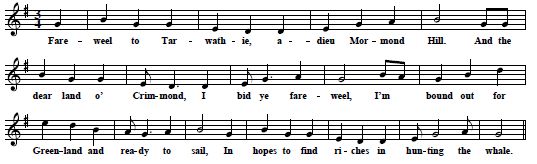

Fareweel to Tarwathie, adieu Mormond Hill, "Farewell To Tarwathie" was first recorded not by Lloyd himself but by Ewan MacColl for the LP Thar She Blows! (Riverside RLP 12-635, 1957) which was reissued in the 60s as Whaling Ballads (Washington WLP 724, both links to ewan-maccoll.info, see also Mainly Norfolk). These were both American releases. This recording is today available in a collection with the title Ewan MacColl, A.L. Lloyd, Peggy Seeger & John Cole, Whaling Ballads: Master of Mid Century Folk Music that I once saw at iTunes. McColl and Peggy Seeger also published the text and tune of this song in 1960 in their important and influential collection The Singing Island. A Collection of English and Scots Folksongs (No. 56, p. 63) and it was also included in MacColls Folk Songs and Ballads of Scotland (Oak Publication, 1965) although the latter of course postdates Dylan's recording. A. L. Lloyd only recorded the song in 1967 for the LP Leviathan! Ballads and Songs of the Whaling Trade (Topic 12T174, now Topic TSCD497, 1998, see Mainly Norfolk). According to the notes in The Singing Island (p. 111) A. L. Lloyd had learned "Farewell To Tarwathie" from "John Sinclair, a native of Ballater [Aberdeenshire], in Durban, South Africa, 1938". This is a very dubious claim and most likely simply wrong. It seems that he occasionally took some liberties with the facts, to say at least. Gammon (p. 148, see also Arthur 2012, esp. "The Lloyd Controvery", pos. 754) notes that he was "a reassembler and tinkerer" but these kind of practices were common among singers and publishers of so-called "folksongs". Apparently Lloyd went a step further and even invented fictitious informants for songs he had compiled himself. This was for example the case with "Reynardine", another Folk Revival standard from his repertoire . He once claimed to have learned this piece from one Tom Cook from Suffolk. But Stephen Winick has shown convincingly that "it is unlikely that Lloyd had ever heard anyone sing" this song "before he did so himself". Instead it looks as if he had "constructed his version from fragmentary texts learned from books, filling it out with a broadside stanza" (Winick 2004, pp. 288-9; see also Arthur 2012, pos. 818-855). There is a similar problem with "Lord Franklin". For this song "Edward Harper, a whale-factory blacksmith of Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands" received credit. But it doesn't take much time to find out that Lloyd had created his own fragmentary version with the help a tune and some fragments collected by Elizabeth Greenleaf and Grace Mansfield and then published in their book Ballads And Sea-Songs Of Newfoundland (1933). I have no doubt that "Farewell To Tarwathie" is also one of Lloyd's "fabrications" (see also the remarks in Arthur 2012, pos. 4854 and the discussion in the Mudcat Board). The words to this song are a slightly edited version of a text published by Scottish collector Gavin Greig circa 1909 - I don't have the exact date - in the Buchan Observer in No. LXXXV of his column "Folk-Song Of The North East" (Roud ID S205060). All these articles were also reprinted in a bound edition with the same title that was brought out between 1909 and 1914: Farewell to Tarwathie, adieu Mormond Hill Today the text is easily available in the first volume of the Greig-Duncan collection (I, No. 15, p. 33, notes p. 501). It is an abbreviated and edited version of a poem - not a song - written by George Scroggie from Strichen, Aberdeenshire and published in 1857 (see Copac) in Aberdeen in his book The Peasant's Lyre, A Collection of Miscellaneous Poems (pp. 73-75, available at the Internet Archive):

"There are actually three farms near Strichen having the name Tarwathie (North Tarwathie, South Tarwathie, and West Tarwathie), and no one has yet discovered from which farm the man in the poem might have come. Seafaring was, however, a popular form of livelihood in that part of Scotland, most of the farms, including West Tarwathie, being rather small and unlikely to support growing families. The closest ports then supporting large fishing fleets were Fraserburgh to the north and Peterhead to the east [...] In 1851, just six years before George Scroggie published his little book of poetry, there were perhaps close to a dozen whalermen from Aberdeenshire, any one of whom might have been the person in "Farewell to Tarwathie," intending "To follow the whale." Interestingly Greig had received the text from a relative of the original author, as can be seen from the comments to the song in his column (also in Greig-Duncan I, p. 501): "This song [sic!] was sent by Mr. John Milne, Maud, with a note on its history. It was written he says, by George Scroggie early in the fifties of last century. Scroggie was married to Mr. Milne’s aunt, and was at one time miller at Federate in the parish of New Deer [...] Tarwathie is a very favourable specimen of Scroggie’s versifying powers". Mr. Milne was one of his best and most helpful informants, a hard-working farmer but also a very educated man with great interest for geology, local history, folklore and also folksongs. In fact he had himself collected local songs and published them in a booklet (Greig-Duncan 8, pp. 485 & 570). This text was never collected elsewhere. Greig's article is the only possible source. In fact it never qualified as what is today called a "folksong" and there is not even any evidence that this piece was ever sung or that it was connected to a tune. There is good reason to assume that it was A. L. Lloyd himself who doctored the text a little bit - one verse was dropped and some lines were slightly changed - and then set it to music. In fact "Farewell To Tarwathie" most likely started its life as an "old folksong" only in the 1950s. The melody selected by Lloyd fits perfectly well to the words and I think it was this particular combination that made the song so effective. It is a variant of one of the most durable and popular British tune families. The earliest known printed variants were published in the 1720s and it has been in use since then not only in Britain but also in North America. I will try to sketch here both the British and the American tradition. The first step to understand the history of this group of tunes is to bring the available evidence into a reasonable order. Of course this is still far from being complete but at least it should serve as an helpful overview. ´ A lot of interesting people were involved with this tune, for example classical composers like Joseph Haydn and Arnold Schoenberg, famous songwriters like Robert Burns and Thomas Moore, popular singers like James Balfour from Scotland - now completely forgotten - and John McCormack from Ireland, hymn-writers and country fiddlers and of course numerous collectors of so-called folksongs. Some songs will be discussed more thoroughly while others will only be mentioned in passing. Besides that I will also try to identify the source for the tune variant used by Lloyd for his "Farewell To Tarwathie". But at first we will have to go back to the 1750s to the well-known Scottish composer James Oswald who published some of the earliest versions of this melody in his Caledonian Pocket Companion.

2. The British Tradition - From James Oswald to John McCormack An interesting and possibly very influential early variant of this tune with the title "Earl Douglas's Lament" can be found in the 7th volume of Oswald's important collection (p. 30, at the Internet Archive) that was published in the second half of the 1750s:

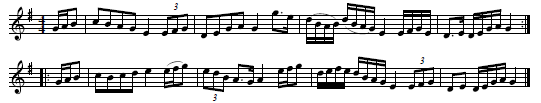

Some more variants were published in subsequent volumes of this series: "Carron Side" in Vol. 8 (p. 44); in Vol. 9: "Lude's Lament" (p.3, here on p. 65 of a later reprint, available at the Internet Archive) and "Armstrong's Farewell" (p.13, dto, p. 75). Another one called "Kennet's Dream" can be found in Vol. 10 (here on p. 106 of that reprint). All except "Carronside" are in triple time. Of course these five tunes are not exactly identical to the one of "Tarwathie" but the close relationship is easily audible, especially in the first strain of "Armstrong's Farewell":

James Oswald (1710 – 1769) was the "most prolific and successful composer of 18th-century Scotland", also a publisher, music teacher, arranger and cellist. He worked at first in Dunfermline and Edinburgh, moved to London in 1741 and in 1761 he even became chamber composer to King George III. Between 1745 and 1765 he published 12 volumes of the Caledonian Pocket Companion, a "cheap collection of one-line tunes suitable for flute, violin, or [...] any other instrument. This work was to be the success of Oswald's life" (Johnson/Melvill in New Grove, 2nd ed., Vol. 18, pp. 790-1, see also Kidson, British Music Publishers, pp. 84-87). The tunes included in this series of books are never credited and it is very difficult to know where he got them from. A lot of these pieces may have been written by Oswald himself, who - as noted by Johnson and Melvill in their article in the New Grove - knew that "there was no such thing as a new tune, only recycled old ones" and that "presenting one's work as 'traditional' could often help its acceptability". It is not clear if "Earl Douglas's Lament" was a "new" song. There is a good possibility that it refers to a popular play of that time, John Home's Douglas. This tragedy - based on the the Scottish ballad "Gil Morrice" - was first staged in Edinburgh in December 1756 and then in London at Covent Garden in March 1757. Oswald was a friend of Home and he also had suggested to use this ballad (see Wolbe 1901, pp. 4-10). John Glen (1900, p. 169) in his Early Scottish Melodies notes that it is "probable both the song and tune were written for Home's tragedy". But I found no evidence that it was actually performed on stage. Perhaps it was only an attempt to cash in on the play's success. Nor do we know who has created this tune. But it is not unreasonable to assume that it was in fact Oswald himself. But we know that this melody was not entirely anew. It is related to an older Scottish tune called "Daft Robin" or "Robbi donna gòrach" that was first published nearly two decades later, circa 1775, in Daniel Dow's Collection of Ancient Scots Music for the Violin Harpsichord or German Flute Never before Printed (p. 25, available at WireStrungHarp):

But the tune definitely existed already before the publication of "Earl Douglas's Lament" because the it can also be found in a manuscript from around 1740 with the title A Collection of the best Highland Reels written by David Young (see Glen, p. 145 - here called the McFarlan manuscript - and Cook et al. 2011, p. 72, here as the Drummond Castle Manuscript (c 1740), NLS MSS 2084 & 2085):

Here we can also find the distinctive melodic motif that is common for this family of tunes. But interestingly it is not in triple but in common time and also in minor instead of major. This tune has an history of its own. Variants were also published in Patrick MacDonald's A Collection of Highland Vocal Airs (Edinburgh 1784) and - as an "Old Highland Song" - in Niel Gow's Collection of Strathspey Reels (Edinburgh 1780s, here p. 37 in a probably illegal London reprint, n. d., at Google Books). In James Johnson's Scotch Musical Museum we find it as "The Captive Ribbard (A Galic Air)". The text was written by Dr. Thomas Blacklock (Vol. 3, 1790, No. 257, p. 266, see also Dick 1903, p. 455). Robert Burns also wrote a new set of lyrics for this melody: The Thames flows proudly to the sea, How lovely, Nith, thy fruitful vales, This was included in the third volume of the Scots Musical Museum (No. 295, p. 305). Here "Robie donna gorach" is in fact indicated as the tune but the editor instead used a different one written by Robert Riddell - most likely because the original melody had already been used for "The Captive Ribbard". The song was first published in its correct form only in 1903 by James Dick in his Songs of Burns (pp. 243 & 454). Interestingly this tune is also related to an older Irish piece that first appeared in print in the Colection [sic!] of the most Celebrated Irish Tunes published by William and John Neal in Dublin 1724. Here it was called "Ye Bockagh" (p. 26, available at ITMA). Five years later, in 1729, Charles Coffey included a variant called "Did you not hear of Boccough" in his opera The Beggar's Wedding (Act 3, tune 21):

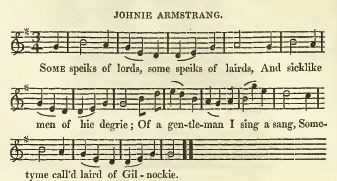

As late as 1792 Edward Bunting collected a version with the title "Bacach Buidhe Na Léige" ("The Yellow Beggar Of League"). He was told that it was composed by the famous harper Rory Dall O'Cahan in 1650 (see O'Sullivan, No. 20, p. 34-5). This tune is also in common time but again the distinctive melodic motif is easily dicernible. Even Patrick Joyce included a variant called "Diarmuid Bacach - Lame Dermot" in 1909 in his Old Irish Folk Music And Songs (No. 760, p. 374, at the Internet Archive; also available at ITMA). It is not clear how these tunes are related to each other and to "Earl Douglas's Lament". Is the latter derived from one of the earlier pieces or from another older undocumented tune? Equally unclear is the origin of all the variants published by Oswald in Volumes 8, 9 and 10 of the Caledonian Pocket Companion, "Carronside", "Lude's Lament", "Kennet's Dream" and "Armstrong's Farewell". It is possible that the latter refers to an old ballad from the 17th century called "Johnny Armstrong's Last Good-Night "(see f. ex. Pepys 2.133 at EBBA, Child 169). But Simpson in his British Broadside Ballad and Its Music (1966, pp. 401-2) notes correctly that "because of the gap [...] between the ballads and the tune itself, it is not possible to propose the identification with much confidence". Even though it may not be as old as he ballad there is a certain possibility that a precursor of "Armstrong's Farewell" at least predates "Earl Douglas's Lament". Interestingly Scottish antiquarian William Stenhouse heard in his "infancy" a version of this song called "Johnie Armstrang" from "Robert Hastie, formerly town-piper, of Jedburgh who was a famous reciter of the old Border Ballads" that was only published posthumously with his notes for the Scots Musical Museum in 1853 (pp. 335-6):

Stenhouse was born in 1773. That means he must have witnessed Hastie in the late 70s or early 80s, nearly two decades after the publication of Volume 9 of the Caledonian Pocket Companion. We don't know when Mr. Hastie had learned this song. Of course it could have been a more recent adaption of Oswald's piece. But it would also be plausible if this variant was something like a prototype for the Scottish part of this particular tune family. Sadly there is no documentary evidence for this assumption. At this point it is only possible to conclude that it was apparently "Earl Douglas's Lament" from Oswald's collection that started a new line of tradition. In 1778 the tune found its way onto the theater stage. Composer Samuel Arnold (1740 – 1802) included the tune in his Incidental Music for Macbeth. It was one of five popular "Scottish Airs" used here in an orchestral arrangement. The others were "Birks of Invermay", "The Yellow-Haired Laddie", "The Braes of Ballenden" and "Lochaber". The lament, "a chivalrous song of piety and farewell" (Robert Hoskins, liner notes, Naxos 8.557484) was performed at the end of the fourth act. Here we can see that it was already established as a traditional Scottish air, even though it is highly likely that it was at that time not much older than 20 years. Arnold's piece was published again in 1997 by Artaria Editions and a recording by Kevon Mallon and the Toronto Chamber Orchestra has been released by Naxos in 2006 (audio samples available at Classics Online). In the early 1790 three variants of the tune were included in the Scots Musical Museum. In Vol. 3 (1790, No. 275, p. 284) we find "Todlen Hame" and in Vol. 4 (1792) "Lady Randolph's Complaint (Tune: Earl Douglas's Lament)" (No. 343, pp. 352-3) and "Johnie Armstrong" (No. 356, p. 367).

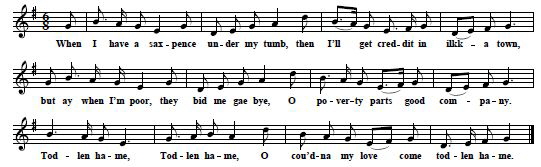

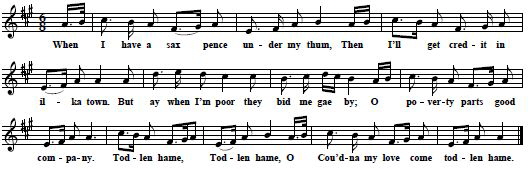

The latter two of course refer to the variants published by Oswald. But most interesting is "Todlen Hame". The words were first published in 1726 by Allan Ramsay in the second volume of his Tea-Table Miscellany (here on pp. 159-60 of the 10th edition, Dublin 1734). Ramsay had marked the song with a "Z". These were "Auld Sangs brush'd up some of them with Additions by the Publisher" (see there p. 348). So possibly some of the verses were written by the editor. In 1733 the song was printed with music in the second volume of William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius (No. XLI, p. 93). But the tune used there was completely different. One may assume that it was the original one. The text was reprinted regularly during the next decades. It can found for example in David Herd's Ancient and Modern Scots Songs (1769, p. 191). Only in the second half of the 1780s this song was published with a new melody: first in a songbook called The Musical Miscellany; A Select Collection Of The Most Approved Scots, English, & Irish Songs, Set To Music (Perth 1786, Song CLXVIII, pp. 320/1; also in Calliope: Or The Musical Miscellany [...], London & Edinburgh 1788, Song CCXXX, pp. 428/9):

This is a very simple variant of the tune, just one melodic line repeated four times with an additional refrain. The version in the Scots Musical Museum offered a little more variation. Here a musically distinctive middle-part was added. Its structure is a-a-b-a.

"Todlen Hame" was a particular favorite of Robert Burns. He once called it "perhaps, the first [i. e. best] bottle song that ever was composed" and also noted that it was "for wit and humor, an unparalleled composition" (Gebbie V, p. 404 & p. 275). In fact this song was apparently very popular at that time. Publisher George Thomson wrote in a letter to Burns from September 1793 that "Mr. James Balfour [...] the best singer of the lively Scottish ballads that ever existed, has charmed thousands of companies [...] with "Todlin [sic!] Hame" (Gebbie V, p. 230). We also find this piece in other tune or song collections from this era like James Aird's Selection Of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs (Vol. IV, 1794, No. 200, p. 74) and in the second volume of Urbani's Selection of Scots Songs (Edinburgh, ca. 1794). The latter - an Italian musician living in Edinburgh where he was busy both as a musician and music publisher (see Kidson 1900, p. 199) - did not only include an arrangement of "Todlen Hame" (p. 6-7, available at the Internet Archive) but also combined the tune with Robert Burns' "Banks o' Doon" (p. 4-5). That text had been published with another tune in the fourth volume of the Scots Musical Museum in 1792 (No. 374, p. 387; see also Dick, No. 123, pp. 112 & 392-3). The version in publisher William Napier's Selection of Original Scots Songs (Vol. 3, London 1795, p. 7, at the Internet Archive) was arranged by Joseph Haydn:

In the late 18th and early 19th century publishers like Napier, William Whyte and George Thomson brought out a considerable amount of collections of "Scots Songs". They were all eager to give these old tunes a more modern sound to make them acceptable to contemporary listeners. Therefore they hired the star composers from the continent - Haydn, Pleyel, Kozeluch and later even Beethoven - to write arrangements. Joseph Haydn also arranged two related songs for Napier, "Johnie Armstrong" and "Lady Randolph's Complaint" - both like "Todlen Hame" borrowed from Johnson's Museum - that were published in the second volume of his collection in 1792 (p. 10 & p. 28; see also Friesenhagen 2001, No. 109, pp. 16-7 & No. 127, pp. 46-7). A couple of years later he went back to "Todlen Hame", this time for William Whyte who included this new arrangement in Vol. 2 of his Scottish Songs, Harmonized Exclusively by Haydn (1807, see Friesenhagen & Hiller 2005, No.425, pp. 161-2). Interestingly George Thomson didn't include this song in his very ambitious Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs that was published since the 1793. In fact he had commissioned an arrangement from Austrian composer Leopold Kozeluch but only included it in 1822, four years after the composer's death, in the second volume of The Select Melodies of Scotland (No.19), the so-called octavo edition:

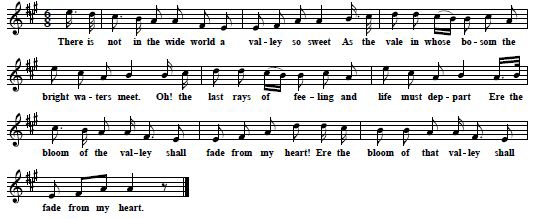

The problem was that Mr. Thomson didn't like the original text. He once noted that the words, "though not without merit, are of a cast too broad and vulgar for the present generation" (Hadden, p. 238). But Scottish poetess Joanna Baillie wrote a new set of lyrics for him. He was duly impressed with her work and praised her accordingly: "You have really done honour to "Todlin Hame' [...] Your thoughts on that subject will evermore delight good company [...] I shall indeed be as proud as a peacock of 'Poverty parts good company' appearing in my book" (Hadden, pp. 238-9): When white was my o'erlay as foam on the lin, After the turn of the century more variants of this tune were published. An instrumental called "Drunk at Night and Dry in the Morning" was first printed in London in 1804 in O'Farrell's Collection of National Irish Music for the Union Pipes (p. 19, at IMCO). This was apparently the melody of a popular song from the 1780s. A text with the title "The Irishman's ramble; or, drunk at night and dry in the morning" can be found in two Scottish chapbooks. One with "Three Excellent New songs" was published in 1784 (ESTC T174859, available at ECCO) and another one - "Two Excellent New Songs" - is dated as from 1790 (ESTC T177941). This is a very long humorous ballad and not exactly a masterpiece of songwriting. Here I will only quote the first two and the last verse: My name's Patrick Kelly, a stout roving blade, As far as I know text and tune were never printed together. The latter was subsequently also published in O'Farrell's Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, Vol. 1, 1805, p. 59, available the Internet Archive) and in Smollett Holden's Collection of Old Established Irish Slow & Quick Tunes (Dublin 1805, p 25, at IMCO ). Interestingly this was the very first time that a version of this tune in triple time was classified as Irish. But apparently the opinions were divided. In 1806 another arrangement that song found a place in the third volume of Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dance (p. 1, available at the Internet Archive) by the the Gows. In fact at that time this tune was described both as "National Irish Music" and as an "Original Scots" dance. But this should come as no surprise because it had taken root both in Ireland and in Scotland. The only question is if this particular variant was derived from "Earl Douglas' Lament" á la James Oswald or if it is based on other earlier undocumented versions of this tune. But there is good reason to assume that Oswald was the original source for all the variants in triple time. A version of this tune was also used by Thomas Moore for "The Meeting Of The Waters". This song was included in the first volume of his Selection of Irish Melodies that was published in 1808 (pp. 62-3):

Strangely the name of the "Air" is given as "The Old Head Of Denis". That may have been was an older, previously undocumented Irish variant in triple time. But again it is impossible to find out if it existed before the first publication of "Earl Douglas's Lament":

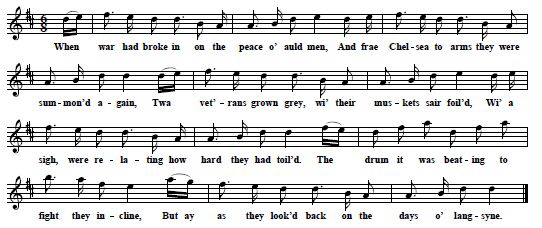

Another variant with the title "My Name Is Dick Kelly" was included in 1809 by John Murphy in his Collection of Irish Airs & Jiggs with Variations (Edinburgh 1809, p. 38, at IMCO). It is not clear if this was a song - I wasn't able to find the text - or only an instrumental tune. One more Scottish version, the nostalgic "The Days Of Langsyne", can be found in Crosby's Caledonian Musical Repository (Edinburgh, 1811, p. 250):

It was always common practice to use well known old tunes for new songs and it seems that this particular melody was immensely popular at that time both in Ireland and Scotland. Another variant form - apparently derived from "Todlen Hame" - was also adopted for "My Ain Fireside". The words were written by Scottish poet Elizabeth Hamilton circa 1806. Here is the version published in 1853 in Davidson's Universal Melodist (p. 30):

In the same songbook we also can find another version of the tune, this time used for "The Green Bushes" and described as an "Old Irish Melody" (p. 25) . This particular song was popularized in 1845 by actor and singer Fanny Fitzwilliam who performed it on stage in The Green Bushes, or A Hundred Years Ago, a play by William Buckstone that was set in Ireland and America at the time of the the rebellion. In fact she never sang the whole song but only snippets in Act 1 and Act 3 (see Baring-Gould, Songs Of The West, notes to No. XLIII, p. xxv). Nonetheless it became a big success was subsequently published as sheet music and in popular songbooks like the Universal Melodist:

The song itself was older than the play. The words were first published on broadsides at least two decades earlier. The oldest dateable version seems to be a song sheet by an unknown printer from 1827. Here - as in other early prints - it was called "The False Lover" (Firth c.18(145), at Broadside Ballads Online). The words are nearly identical to Mrs. Fitzwilliam's version but the second verse ("O! why are you loitering her [...]") is missing. The same text was also printed by Pitts in London who was busy between 1819 and 1844 (see Harding B 17(4b)). Pitts also published a somehow related song with the title "Among The Green Bushes" (dto). Another song called "Sweet William" was put out by the London printer Catnach - in business between 1818 and 1838 - and here "Green Bushes" is given as the tune (Firth c.13(10)). But it is not clear if this was the same melody as the one used by Fanny Fitzwilliam on stage. In fact there is a good possibility that the older versions of this song were sung to other tunes. In 1855 Thomas Hepple, a "local singer" from Kirkwhelpington in Northumberland sent a collection of 24 songs to the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. These were, in his own words, "some old ballads I have had off by ear since boyhood" (see Lloyd, Foreword to Bruce/Stokoe, pp. vi, xi; Rutherford 1964, pp. 270-2). One of them was "The Green Bushes" with the text nearly the same as on the broadsides of "Forsaken Lover" and a tune completely different from Mrs. Fitzwilliam's (available at FARNE; this variant was also reprinted in Roud/Bishop, No.45, see also the notes there). Folksong collectors since the 1880 noted some more versions of this song but they were also mostly combined with other melodies. Examples can be found in the publications of Patrick W. Joyce (Ancient Irish Music, 1873, No. 23, p. 25), Sabine Baring-Gould (Songs Of The West, 1891, No.XLIII, notes, p. xxv, song, pp. 90-1; see also his manuscripts, f. ex. Fair Copy, SBG/3/1/229, at the Full English Digital Archive), Frank Kidson (Traditional Tunes, 1891, pp. 47-8) and Cecil Sharp (One Hundred English Folksongs, No. 40, pp. 92-3, notes p. xxx). In fact I know only of two English variants with a tune derived from the one used in Buckstone's play. One was collected by Anne Geddes Gilchrist in 1907 in Sussex although in this case it has been changed considerably and the original melody is not always recognizable (AGG/3/6/16a at the Full English). The second one was noted by George Gardiner who heard it in 1907 in Portsmouth from one Frederick Fennemore. Here the original melody was simplified a little bit but has remained more or less intact (see GG/1/14/869, at the Full English). It was also collected in Ireland by Sam Henry in 1926, apparently from two informants. But in this case the b-part of the tune sounds different (Huntington & Hermann 1990, p. 395). I know of no evidence that this song was sung to that tune before Buckstone's play. There is good reason to assume that words - with an additional second verse - and melody were first combined for that occasion. It is not known who has arranged this piece. Later both Buckstone and one F. W. Fitzwilliam - either Mrs.Fitzwilliam herself or her husband, but his name was Edward - were credited as the authors (see Copac for sheet music published in 1872). Nor is it clear what earlier version of this tune had served as a source for the arranger. The structure of the tune is a-b-b-a, just like "Meeting of The Waters" but the melody is not exactly identical either to Moore’s song. This song was apparently quite popular for a while. But after the turn of the century it became more or less an "oldie" on the way to oblivion until the great Irish singer John McCormack recorded Mrs. Fitzwilliam's version in 1941 at the Abbey Road Studios with Gerald Moore at the piano (see the discography on the site of the The John McCormack Society; an mp3 is available at the Internet Archive). The arrangement - by Frederick Keel - was also published as sheet music at around the same time (see Copac). As late as 1963 a variant of "The Green Bushes" with this tune was collected by Ewan MacColl. He heard it from Charlotte Higgins. She was from a family of Scottish Travellers and 70 years old at that time (see MacColl/Seeger 1977, No. 66B, pp. 223-4; p. 33). From all these example listed here we can see that variant forms of this particular tune have been in use on the British Isles for nearly three centuries - if we start with "The Bockagh" from Neale's Collection that was printed in 1724. I am pretty sure I have missed some versions. For example the earliest Irish variant from oral tradition was published by George Petrie in 1855 in his Ancient Music of Ireland (Vol. 1, pp. 36-7, available at thew Internet Archive). He had collected it in 1837 in Rathcarrick, Sligo. His informant was "a woman named Biddy Monahan [...] a rare depository of the melodies which had been current in her youth in the romantic peminsula of Cuil Iorra" (dto. p. 7):

Unfortunately Petrie had forgotten the original name of the tune. Here it was called "The Blackthorn Cane With A Thong". This was a song written by poet Owen Roe O'Sullivan (+1785) and that was the title under which the melody was at that time "generally known throughout Munster, both as a song-tune and a jig". He suspected that it may be "the original form of the tune called 'The Old Head of Denis'", but this appears to be a very dubious assertion. Petrie also noted that "many other songs have been written to this air in the south of Ireland" including one "about the year 1670" although I couldn't find any documentary evidence for the latter claim. In Ireland a variant form of our tune was even used for a game song (see Petrie 1172, p. 297 and Journal Of The Irish Folksong Society 21, 1924, No. 18, pp. 44-6). Other Irish versions were published for example in O'Neill's Music of Ireland (1903, No. 222, "A Stranger In Cork", available at Freesheetmusic.net, see also abcnotation.com) and in Joyce's Old Irish Folk Music (1909, "O Lay Me In Killarney", No. 652, p. 329, at the Internet Archive; also available at ITMA). In Sam Henry's Songs Of the People three more songs with this this melody can be found: "Bonny Woodha'", "Owenreagh" and "There's A Dear Spot in Ireland" (see Huntington/Herrmann 1990, pp. 84, 217, 220). From Scotland we know for example a song called "The Bonnet O' Blue" that was published in Robert Ford's Vagabond Songs (1904, pp. 212-4) and a fragmentary version of "Fair Flower Of Northumberland" (Child 9) collected The Rev. Duncan. The tune's first strain shows some influence from our song family (reprinted in Bronson I, No. 9.7, p. 142):

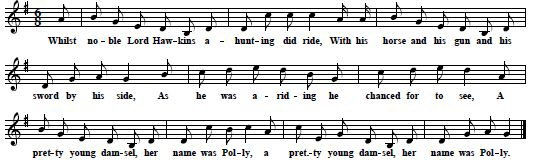

Some variants of the tune were also collected in England, for example "Noble Lord Hawkins", a version of the ballad "Sir Arthur And Charming Mollee" that was noted by H. E. D. Hammond in Dorset in 1905 (HAM/2/10/11 at the Full English, also Gilchrist et al. 1930, p. 177, available at jstor). The original melody is clearly recognizable although it has been varied a little bit. The tune's structure is a-a'-b-a and it was clearly not derived from "The Green Bushes":

But sometimes I am a little bit skeptical. This is for example the case with "Sweet Europe", a version of the broadside ballad "The Happy Stranger" (also related to "The Green Bushes", see Johnson Ballads 365 at BBO, printed by T. Evans, London, between 1790 and 1813, see also Roud Index No. 272) that was included by Cecil Sharp in the second volume of his Folk Songs From Somerset (1905, No. XLVI, pp. 41-2, notes p. 72, available at IMSLP; also in Baring-Gould/Sharp, English Folk-Songs for Schools, 1906, No. 22, pp. 46-7 as "Sweet England", available at IMSLP). Cazden, Haufrecht and Studer in their Notes and Sources for Folk Songs of the Catskills (1982, p. 68) list it as a related tune. But I must admit that I am not convinced:

Nonetheless this tune family has an impressive history on the British Isles. Songwriters, arrangers and composers - as well as the "Folk" - have regularly recycled this melody and created variant forms. It was especially popular in both Ireland and Scotland. But interestingly none of the versions I know is identical to the modern form, the tune used by A. L. Lloyd for "Farewell To Tarwathie". It seems to be most closely related to Stenhouse's "Johnie Armstrang". That variant's structure is also a-a'-b-a. But the b-part is strikingly different from Lloyd's tune and I seriously doubt that this was the blueprint for the melody of "Tarwathie".

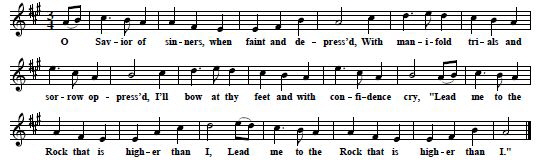

3. The American Tradition I: Hymns, Horses & Old British Hits This tune family also migrated to North America. Of course the immigrants brought their music with them. But British and American culture were closely connected and what was popular in London often also found its way across the ocean very quickly. The people also used the tune for new songs and created a genuine American tradition. The earliest documented variants from the USA can be found in a couple of popular collections of hymns published since the 1830s. Especially the the Baptist and Methodist hymn-writers loved to use popular melodies for their sacred songs. This is a very fascinating topic but I can't go into it here but only refer to the groundbreaking works by George Pullen Jackson (1933, 1937, 1934) who studied these collections and published many of these "folk hymns" from the 19th century anew. The first known example is from a Methodist songbook. In the Wesleyan Harp, edited by A. D. Merrill and W. C. Brown and printed in Boston in 1834, we find a hymn with the title "Lead Me To The Rock" (see Jackson 1943, No. 76, p. 98). The tune used here is very similar to Thomas Moore's "The Meeting Of The Waters":

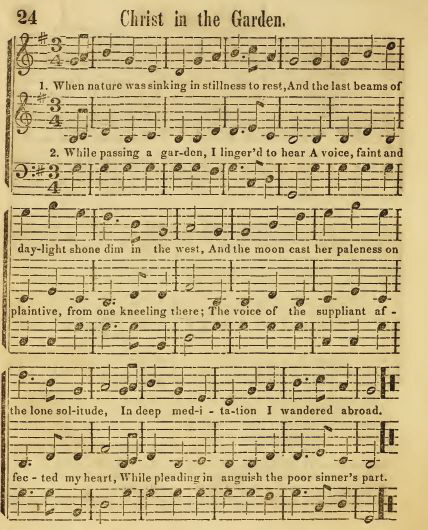

Eight years later another hymn called "Christ In The Garden" was included in three collections, both Methodist and Baptist. The version in H. W. Day's Revival Hymns set to some of the most familiar and useful Revival tunes, many of which have never before been published (Boston 1842; see Jackson 1943, No. 12, p. 28) is in simple a-a-b-a - form, but apparently not derived directly from the old Scottish "Johnie Armstrong" á la Stenhouse. The same song with some minor melodic variations can also be found in M. L. Scudder's Wesleyan Psalmist, Or Songs Of Canaan (Boston, 1842, p. 80). Here the structure is a-b-b-a. An identical version of the tune was also published in a slightly different arrangement in Revival Melodies, Or Songs of Zion. Dedicated to Elder Jacob Knapp (Boston 1842, pp. 24-5, available at the Internet Archive). It seems this hymn was very popular in Boston that year:

The introductory note to the Revival Melodies says that this collection "embraces, in addition to others, not before published, those popular and favorite hymns as they were originally sung at the meetings of the Rev. Mr. Knapp", the well known Baptist evangelist. Apparently the song was not borrowed from Daily's book. In fact another piece - "O Wish You Well" (p. 23) - was reprinted "by permission" and the source is duly credited. One may assume that that this would also have been the case if "Christ in The Garden" had been taken from the "Revival Melodies". As noted the two variants are different from each other and it seems more likely that they represent the work of two independent arrangers. Interestingly the closest British relative is the version of the melody used for "The Green Bushes". But that was first performed and published in London some years later. It is possible that they both derive from an otherwise undocumented common ancestor. This must have been a very successful book. In 1853 a new expanded edition with the title Conference Melodies, or Songs Of Zion - no mention of Elder Knapp here - was published in Cincinnati and New York. On the titlepage the publisher boasts of "45.000 Copies Sold". One may assume that many people were familiar with this particular hymn. Unfortunately we don't know the author of the text nor when it was written. But to my knowledge it wasn't printed before 1842. But at least it is obvious that "Christ In The Garden" remained popular for quite a while. After 1842 the text was regularly reprinted in other publications. We find it for example - with only ten verses and some minor variations - in Joshua V. Himes' Millenial Harp. Designed For Meetings Of The Second Coming Of Christ. Improved Edition (Boston 1843, Hymn 67, pp. 79-80). It had not been included in the first edition (Boston 1842) so perhaps he only heard the hymn that year and then added it to his collection. Interestingly the words were also published in England in 1845, in the Rev. John Stamp's The Christian's Spiritual Songbook (No. 401, pp. 154-5). This is a very interesting collection of "Spiritual Songs Adapted To Popular Tunes": "Why should the devil have all the best tunes?" was of the language of the Wesleys [...] Every person is aware of the almost omnipotent influence of national ballads on national morals, and thus on the formation of national character [...] when the Angel of Doom shall reward the history of ballads, it will be seen that they have corrupted the morals, polluted the hearts, and damned the souls of millions. The first race of Methodists gave a mighty cheek to profane song singing in the following manner: - Whenever they found that the devil had got a tune that seemed to charm the people,some one immediately composed a hymn, or spiritual song, to that tune, and thus cheated Satan out of both tune and singers" (quoted from the Preface). Here the tune for this hymn is given as "Cliff.". This isn't of much help but perhaps it refers to the Rev. John Cliffe, "Late of America, Whose Spiritual And Lively Singing Has Been Blessed To The Salvation Of Thousands" to whom this book was dedicated. But this was apparently the only British publication of this text. Later it was included only in some more American collections, for example in John Dowling's Conference Hymns. A New Collection Of Hymns, Designed Especially For Use In Conference And Prayer Meetings And Family Worship (New York 1849, No. 67, pp. 76-7) and in the Revival And Camp Meeting Minstrel (Philadelphia, ca. 1867, No. 192, pp. 192-3). But the song was also published with this tune, for example in the The Wesleyan Sacred Harp (Boston, Cleveland & New York 1855, p. 204) and in J. Aldrich's Sacred Lyre. A New Collection Of Hymns And Tunes For Family And Social Worship (Boston, New York & Cincinnati, 1860, p. 47). These were arrangements for four instead of three voices. The version in J. Dadmun's The Melodeon. A Collection Of Hymns And Tunes With Original And Selected Music Adapted for all Occasions Of Social Worship, (Boston 1860, p. 85) is a straight copy from the the Wesleyan Sacred Harp, alas without acknowledging the source:

But this hymn was also sung to other tunes, as can be seen from the versions in the Jubilee Harp, A Choice Selection Of Psalmody, Ancient And Modern (Boston 1867, No. 571, p. 315) and in A. S. Hayden's Sacred Melodeon (Cincinnati 1868, p. 240). In 1909 Edmund S. Lorenz, in his book Practical Church Music, remembered it as a "favorite" song from "over forty years ago" and he had heard it with at least three different melodies. He prints two of which one is our standard tune (pp. 94-5). Much later, in the 1930s or 40s I presume, Helen Hartness Flanders collected a version from oral tradition in Vermont with still another tune (see Jackson 1943, No. 13, pp. 29-30). What we know is that this particular hymn was very popular for a couple of decades and it was sung to at least five different melodies. The one from our tune family was apparently the most common, at least in the Northeast where all these collections were published. In 1855 another interesting book of religious songs was published and that was the first from the South where we can find variants of the tune discussed here:

John Gordon McCurry (1821-1886, see Chase 1955, p. 198) was a Baptist missionary, a farmer and a singing-school teacher from Hart County, Georgia. According to his preface he had taught "for the last fourteen years". The Social Harp includes 222 pieces of which a considerable number was borrowed - without permission and acknowledgment - from B. F. White's Sacred Harp (first published 1844). Mr. White was apparently a little miffed about Mr. McCurry's methods (see Steel 2006, p. 136). The two songs of interest here are "Separation New" (p. 23, also Jackson 1943, No. 24, p. 40) and "John Adkin's Farewell" (p. 100, at Google Books), both more secular than religious but with an appropriate moral message. The former is a typical parting song and authorship is claimed by B. J. Stalnaker, also a farmer from Hart County. But the text is known from a song called "Imandra New" that can be found in earlier collections (see Jackson 1943, No. 21, p. 37). The tune's structure is a-a-b-a but it doesn't seem to be derived from the variant used for "Christ In The Garden". Perhaps it represents another line of tradition and was taken directly from oral tradition:

"John Adkin's Farewell" is the sad lament of a drunkard who had killed his wife and was about to executed. This song is credited Mr. McCurry himself but according to Garst & Patterson in their introduction to the reprint (p. xvii) the "text is also found on a 'song ballad' handwritten about 1820 in Johnston County, North Carolina". The tune's structure is also a-a-b-a but with some variations in the a-parts. It is different from both "Separation New" and all the earlier variants:

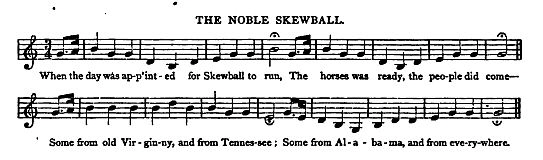

Interestingly this happened to be one of Abraham Lincoln's "favourite songs" (Miller, p. 52). That means it was also sung in Illinois, but it is not clear if the people there knew it from this book. McCurry's version was reanimated during the Folk Revival. Jackson included it in his Spiritual Folk-Songs of Early America (1937) and then Carl Sandburg used the song for his New American Songbag (1950). It was even recorded by Ed McCurdy in 1954 for his LP Sin Songs-Pro and Con (Elektra EKL-24). These hymnbooks show that this particular tune was well known and widespread in North America in the 19th century. Apparently different variants circulated, some in the Southeast and some in the Northeast. Most of them are difficult to relate to the published British versions so perhaps they represent previously undocumented forms of this melody. But on the other these hymnbooks helped spread this tune family further and kept them alive. We have one more early version of this melody but that one is from a completely different genre. In December 1868 Lippincott's Magazine published an interesting article by one John Mason Brown about the "Songs Of The Slave" (pp. 617-623, at Google Books). It is not clear when and where Mr. Brown had heard the songs included here. One of them is a ballad from "many years ago" called "The Noble Skewball": its "popularity among the negroes throughout the slaveholding States was very great" (p. 622):

This is an offspring of song about famous horse-race in Irland from the last decade of the 18th century. The original words were first published in the 1790s, for example as "Skew Ball" in A Garland, Containing Three Choice Songs (Preston, poss, 1790, ESTC T188213) and on a song sheet as "A New Song, Called Skewball" (Belfast, poss. 1795, ESTC T197133, both available at ECCO). This song was apparently very popular in Britain and it can be found on a couple of broadsides, for example one by Pitts in London (between 1819 and 1844, Harding B 11(73) at BBO). But it also migrated quickly to North America and was reprinted there at least since the 1820s, here in the Songster's Museum (Hartford 1829, pp. 3-4):

We don't know the original tune of that song. Perhaps it was this one or perhaps it was something else. Was it already sung in Britain with this particular melody or only in USA? Nor do we know anything about "Money makes he mare go", the air given in the Songster's Museum. Later American versions from oral tradition were sung to different tunes, for example the the one collected in North Carolina in 1915 by Frank Brown (Brown IV, No. 136, pp. 211-2). Nonetheless this is a fascinating find that shows how a British popular song was adapted by the slave population in the USA. This variant's structure is also a-a-b-a, although once again the b-part is different from the other available versions of this tune. Tune and text from John Mason Brown's article were reprinted in 1925 in Dorothy Scarborough's book On The Trail Of The Negro Folk-Songs (p. 63) and thus made available to all interested readers and scholars. The hymns mentioned above as well as "The Noble Skewball" represent a genuine American tradition. But at least some of the original British songs using tunes from this family were well known in North America. Thomas Moore's works became immensely popular (see Hamm, p. 44-59) and "The Meeting Of The Waters" was easily available throughout the 19th century. The text can be found in songbooks like The United States Songster. A Choice Selection Of About One Hundred And Seventy Of The Most Popular Songs (Cincinnatti 1836, p. 8) and on song sheets, like one printed by de Marsan in New York in the 1860s (available at America Singing: Nineteenth-Century Song Sheets, LOC). The song was published as sheet music, for example by Dubois in New York, Graupner in Boston, Carr's Music Store in Baltimore and Willig, also in Baltimore, the latter even with "additional Words By a Gentleman" (all n. d., available at the Lester S. Levy Collection). It surely was a tune that everybody knew and it was also used for new songs. The "Saugerties Bard", Henry Sherman Backus (1798-1861), was an "itinerant peddler" who wrote about crimes and other shocking incidents: "Murder, disaster, tragedy, and sorrow were [his] stock in trade" (see Thorn 2005, available at New York Folklore Society). The title of "Heart Rending Tragedy, or Song No. 2 on the 30th Street Murder" (New York, n. d., ca. 1858) says it all and I wonder what Thomas Moore would have thought about this piece. Other new works were "The Irish Brigade No.2" by one John Flanagan (n. p., n. d.) and "Star Of The West" (Boston, n. d., all available at America Singing: Nineteenth-Century Song Sheets, LOC), a song performed "at the Erin Benevolent Society, by Mr. M'Farland, with unbounded applause". Elizabeth Hamilton's "My Ain Fireside" was also published as sheet music, for example by G. Willig in Philadelphia (n. d., available at the Lester S. Levy Collection). This version was surely imported from Britain. On the title page it is called "a celebrated Song as Sung by Mr. Sinclair. Arranged for the Piano Forte by John Parry". Sinclair was a popular English singer and Welsh composer John Parry had published his arrangement of "My Ain Fireside" - "with Symphonies and Accompaniments" – in the 1830s (see Copac). But we find this song also in popular songbooks like One Hundred Songs of Scotland (San Francisco 1859, p. 30, at Google Books) and – only the text – in cheap songsters like Beadle's Dime song Book No. 4 (New York 1860, p. 49). Both "The Meeting Of The Waters" and "My Ain Fireside" were also included by Helen Kendrick Johnson in her "Our Familiar Songs" (New York 1889, p. 267, p. 46), a massive collection of the most popular songs of the 19th century.

Even "The Green Bushes" made it across across the ocean. The text was published on song sheets, for example by Andrews in New York (n. d.) - here only four verses - and words and music were available in songbooks like One Hundred Comic Songs (Boston 1858, p. 11, available at Sibley Music Library).

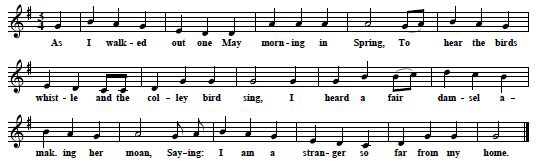

4. The American Tradition II: Recycling "Old Folksongs" It is obvious that this tune family discussed here was well known and widely spread in North America during the 19th century. But what we know is very little of what really happened. Much of the musical life remained under the radar of the music publishers. Since the early years of the 20th century the collectors of the so-called "folksongs" added some small pieces of the puzzle. They were interested in "old" songs, not from urban areas but from the rural backwoods. The very first "Folk"-version of this tune from the early 20th century was collected and published by Emma Bell Miles (1879-1919). She was originally from Indiana but moved to Walden's Ridge near Chattanooga in Tennessee at the age of nine where she later married a "mountain man". Ms. Miles had studied art and she "lived a bicultural existence, dividing her time between Chattanooga where her artwork made her popular among the moneyed classes, and the small cabin on Walden's Ridge she shared with" her husband and their children (McCauley 1995, p. 80; see also Wikipedia). That made her more of an "insider" than many later professional song collectors. In 1904 she published an interesting article about "Some Real American Music" in Harper's Monthly Magazine (Vol. 109, pp. 118-123, available at Hathi Trust Digital Library): "It is generally believed that America has no folk-music, nothing distinctively native out of which a national school of advance composition may arise [...] But there is hidden among the mountains of Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Carolinas a people of whose inner nature and its musical expression almost nothing has been said. The music of the Southern mountaineer is not only peculiar, but, like himself, peculiarly American" (p. 118). Her first example is an untitled fragment with four verses and a very simple tune. But the distinctive melodic motif is still discernible. A year later she included this piece in her book Spirit Of The Mountains. Two verses were then incorporated into another song but instead she added an additional one (p. 148):

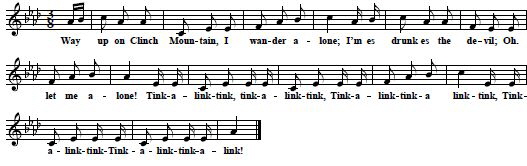

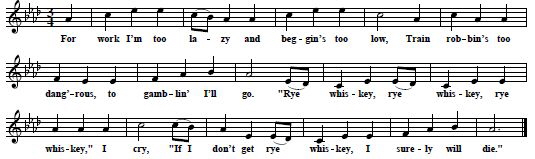

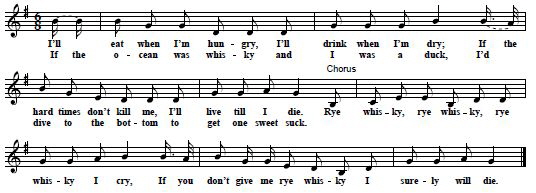

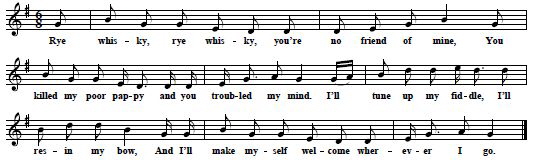

I'll tune up my fiddle and rosin my bow, Another early variant of the same song from around the same time was discovered by Edward C. Perrow. He was from Virginia, grew up in Tennessee and made his Ph. D. at Harvard during the "reign" of Lyman Kittredge, Professor Child's successor. Since 1911 Perrow was Professor of English at the University of Louisville, Kentucky. Between 1912 and 1915 he published a series with the title "Songs And Rhymes From The South" in the Journal of American Folklore. This was a very valuable collection and Richard Mattheson (at Bluegrass Messengers) is surely right in calling him "one of the first outstanding song collectors" in the United States. In 1905 he had heard a "Drunkard's Song" from "mountain whites" in East Tennessee. This piece was published only in 1915 in the third part of his series in the Journal (pp. 129-30). It has some more verses – one of them identical to Ms. Miles version - and looks like a more complete song:

Way up on Clinch Mountain, I wander alone; The tune used in these two variants has the most simple form imaginable. It is only the a-part but no second strain as in the American versions known from the 19th century. Either this is a reduced form of the of the more sophisticated variants like "John Adkin's Farewell" and "Noble Skewball" or perhaps a direct descendant of the original Scottish "Todlen Hame" that at first also lacked a musically distinctive middle-part. This is not an unreasonable assumption because that was also a drinking song. But there are no textual parallels to "Todlen Hame". Both Miles' and Perrow's songs consist of a set of only very loosely connected verses that had apparently been drawn from different sources. One couplet is in fact very old. A variant form of the third verse was used by English playwright Robert Dodsley for a song performed in his play The King And The Miller Of Mansfield. A Dramatick Tale in 1737 (p. 40). This song was set to music by composer Thomas Arne (sheet music available at the Internet Archive) although the tune was very different: He eats when he's hungry, he drinks when he's dry, Variants of this couplet were regularly collected in North America. One was for example published in 1926 by Arthur Hudson in the Journal of American Folklore (No. 48A, p. 148). His informant reported that he had "obtained it from Dr. J. M. Henderson, of Waelder, Texas, who recited it and remarked that he heard a drunken negro singing it, to the tune of "Old Hundred", over seventy years ago, on the street of a small town in North Mississippi": I'll eat when I'm hungry Another informant from Mississippi supplied him with a variant where the third line is instead "if the Yankees don't kill me," and claimed that it was a "popular Civil War song". A song called "The Bright Sunny South"- collected in 1918 in Kentucky - with the same couplet in the last verse can be found in John H. Cox' Folk-Songs of the South (No. 76B, p. 280): I'll eat when I'm hungry, I'll drink when I'm dry; Apparently variants of this particular couplet were known in the USA at least since the Civil War era. Some collectors have noted versions of "The Rebel Prisoner" with this verse (see for example Sharp 1932 II, No. 157B, p. 213; Cox No.76, p. 279) although the text published in 1874 in Francis D. Allan's Lone Star Ballads (pp. 80-1) doesn't include it. But perhaps that version is simply incomplete and the editor missed out some verses. It should also be noted that "The Rebel Prisoner" is based on an older British broadside called "The Happy Stranger". I have already mentioned it in the preceding chapter because Cecil Sharp's "Sweet Europe" from Somerset is derived from this song. Versions from oral tradition were also collected in North America, for example by Sharp in the Appalachians (1932, II, No. 157A, p. 212). But all known American variants of this song - both the "Happy Stranger" and the "Rebel Prisoner" - were sung to different melodies and it seems to me very unlikely that it was originally connected to our tune family. Interestingly the "mountain" and the "wild geese" in the fifth verse of the "Drunkard's Song" may also be a relic of the "Rebel Prisoner" or the "Happy Stranger". They also can be found in the version of the latter collected by Sharp in Kentucky in 1917 (1932 II, No. 157A , p. 212): Go build me a castle all on the mountain high, In fact it is difficult to assess how these songs are related to each other. At least we know that they freely shared these kind of floating verses. The same question arises with another phrase from Perrow's text: "En if people don' like me, they ken let me alone". This line points to a verse known from one version of "The Wagoner's Lad" that was published - as "Loving Nancy" - by Wyman and Brockway in their collection Lonesome Tunes. Folk Songs From The Kentucky Mountains (1917, p. 62-4, verse 3): [...] The verse about "Jack u' diamonds" may be a relic of a song about card-playing. In Frank Brown's collection from North Carolina we find four variants, all of them incomplete fragments (Brown III, No. 150, pp. 80-1). The earliest one (var B) with only two verses was noted in 1915. The informant reported that this "song has been sung in this part of the country a good many years. I heard some card-players sing it 18 or 20 years ago": Jack of diamonds, I know you, I know you of old, The melody (Brown V, No. 50B, p. 44) is very different from Perrow's and doesn't belong to the tune family discussed here and that is also the case with the two other tunes from Brown's collection (dto., var C & E, collected 1921 and 1936). My best guess is that this was in fact originally a separate piece sung to different melodies and "Jack o'diamonds" only later - but possibly before the turn of the century - infiltrated our drinking song. Of course this is all more or less guess-work because much of the song's prehistory remains in the dark. The first folklorist to publish a variant this song was John A. Lomax who included a very interesting version with the title "Jack O'Diamonds" in 1910 in his classic collection Cowboy Songs And Other Frontier Ballads. His tune (pp. 295-6) is quite similar to Perrow's although not identical. It is still the simple form without a second strain although the a-part offers a little bit more variation. The structure is more like a-a'-a-a':

I don't know where and when exactly Lomax has collected the song and he fails to give the appropriate contextual information. But he was less interested in folkloristic authenticity and instead his aim was to revitalize these old songs and bring them back into circulation. In the introduction (p. xiii) he "frankly" states that this "volume is meant to be popular". His text (pp. 292-4) consists of numerous verses that look as though they were taken from four or five different songs and it is really not clear if they were all sung to this particular tune:

There are some verses we already know from Perrow's text like the one with "Jack O'Diamonds" as well as "I'll eat when I'm hungry [...]". There is no mention of "Clinch Mountain" but that's only natural if Lomax heard the song in Texas. He was also the first one to unearth verses referring to "Rye Whiskey". That would later become the standard title of his piece. One couplet is a little closer to "The Wagoner's Lad" than the corresponding lines in "The Drunkard's Song": [...] But Lomax also includes another one that we know from some - not all - variants of "The Wagoner's Lad": [...] It can be found not only in the text in Lonesome Tunes (p. 64, verse 3) but also in other versions, for example the one collected in 1908 in Kentucky by Olive Dame Campbell (Sharp 1917, No. 64B, pp. 216-7, also in Sharp 1932, II, No.117B, pp. 124-5): [...] But this particular couplet is much older. It dates back at least to the 1860s. A former slave from Arkansas by the name of Jim Davis, interviewed in the 1930s at the age of 98 years, reported that he was a "banjo picker in Civil War times." One of the songs he "used to pick [...] went like this" (Slave Narratives 2.2, available at Gutenberg.org, also quoted in Tick 2008, p. 236): Farewell, Farewell, sweet Mary; One may assume that this is a fragment of a popular song from that era although I haven't been able to find a commercially printed version. But thankfully some more relics of that piece were collected by other folklorists. Most interesting is a variant from West Virginia that can be found in John H. Cox' Folk-Songs Of The South (No. 146, pp. 433-4). Variant forms of all of its three verses appear in Lomax' "Jack O' Diamonds": Your parents don't like me, And well do I know, Cox received the text - but unfortunately no tune - in 1917 from an informant who claimed that she had learned the words "about forty-seven years ago". That would have been around 1870. We don't know which melody was used for this song. One fragment collected in Missouri in 1931 by Vance Randolph (IV, No.731B, p. 205) was sung to a very different tune but the lone verse is related to one from Lomax' text: My foot's in my stirrup, Here the girl's name is Molly instead of Mary. One more version with another different tune was published by Mary O. Eddy in 1939 in her Ballads And Songs From Ohio (No. 82, p. 200). It includes the opening verse about the "parents" - though in a somehow mutilated form- as well as three more that are unrelated to those from Cox' variant. They refer to the army, the rebels and "good whiskey". Perhaps they were also part of the original song. It is easily possible that this otherwise undocumented piece was one of the precursors of our drinking song and I wouldn't exclude the possibility that it was originally sung to a tune from our family. In a couple of verses of Lomax' text a "rabble soldier" appears and in fact variants of two of them can be found in the "Rebel Prisoner" from Allan's Lone Star Ballads (1874, pp. 80-1, verses 2 & 5):

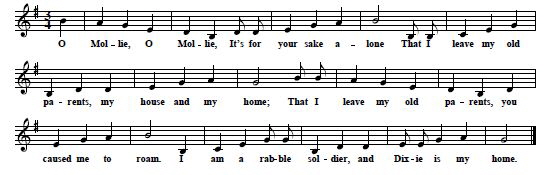

In "Jack O'Diamonds" they look a little bit different: "O Mollie! O Mollie! it was for your sake alone We have already seen a variant form of the first half of the latter stanza in Cox' version of "Farewell, Sweet Mary". Related verses can also be found in some versions of "The Poor/Happy Stranger", for example the one from Kentucky 1917 in Sharp's collection (1932, II, No. 157A, p. 212): Go build me a castle all on the mountain high, Other variants of this stanza appear not only in a song called "Forsaken" - also an offspring of the "Poor Stranger" - that was noted by Katherine Pettit in Kentucky in 1907 but also in the earliest known text of "The Wagoner's Lad" from the same collection (Kittredge 1907, pp. 268-9): I'll build me a castle on the mountains so high, This all looks a little bit complicated but was in fact a completely natural process. Verses like these could easily be applied for different kind of songs. Lomax only made it all little more complicated. What he did was to collate all kinds of stanzas that he thought would fit to this tune. Most likely he had heard different kind of fragments and then simply tried to put these bits and pieces together to create a more complete song. But nonetheless his "new" version of this "old" song was an important stepping-stone. He gave these relics a new life and thus - as will be seen - started a new line of tradition. It is also worth noting that he published this text again in the new expanded edition of the Cowboy Songs in 1938 (pp. 253-255) but this time combined with a different tune. Interestingly two respectively three decades later other folklorists collected texts that are surprisingly similar to Lomax' "Jack O'Diamonds". In Arthur Hudson's Folksongs of Mississippi (1936, but already completed in 1930, No. 117, pp. 258) we find a song with the title "O Lillie,O Lillie" (here as pdf-file). The girl's name is different but otherwise most of the verses known from the text in the Cowboy Songs reappear. Hudson's informant was one A. H. Burnette "who learned it from his father". But unfortunately he didn't tell the collector when exactly he had learned this piece. In 1941 Ronald L. Ives published another closely related text, this time from Colorado, in the Journal of American Folklore (pp. 38-9; see the pdf-file with this version). Strangely both editors were apparently not familiar with Lomax' version. Hudson (p.258) claimed that he couldn't "find it in any other collection" and Ives notes that his variant "differs considerably from those published" (p.38). It would be too easy to take these texts as evidence that Lomax' "Jack O'Diamonds" was not collated from different sources but instead represents a genuine combination of verses. I think that is highly unlikely. At that time the Cowboy Songs were surely widely known and I have no doubt that this collection was regarded as an authoritative source and had already deeply permeated the so-called "oral tradition". It seems to me much more probable that in both cases someone simply had a look at that book and then supplemented his version with some additional material from John Lomax' text. Otherwise these close similarities would be too hard to explain. After 1910 some more variants of this song were collected. Vance Randolph (III, No. 405, pp. 136-7) noted one in Arkansas in 1917 - not published at that time but only in 1940 in the third volume of his Ozark Folksongs - that was a little more "authentic". Here it was called "Rye Whiskey". The tune is similar though not identical to Perrow's "Drunkard's Song". Most of verses are known from Lomax' and Perrow's texts: Rye whiskey, rye whiskey, I know you of old, Songs of this type are also known from black tradition. But that should come as no surprise. In fact much of what today is often only regarded as "white" Hillbilly music was also very popular with the black population. Their musicians knew the same songs. They were part of what Charles Joyner once appositely called the "shared traditions" of the South. In 1922 Thomas W. Talley published his book Negro Folk Rhymes Wise And Otherwise. With A Study. Talley (1870-1852), at that time professor for chemistry at Fisk University in Nashville, was from Tennessee. Over the preceding years he had tried to document what he himself knew since childhood but also went out collecting in the countryside and received other material from a "network of informants". In fact it was "the first substantial collection of black non-religious folk music" (Wolfe 1991, Introduction to New Edition, pp. vii – xxvii). Here we can find two related texts. One is a fragment of three verses with one couplet that is known from the other variants: (p. 114): I'll eat when I'se hungry, The second one - with the title "Temperance Rhyme" - also includes variant forms of familiar verses (pp. 209-10): Whisky nor brandy hain't no friend to my kind. Unfortunately Talley's book lacks contextual information for these variants. It would be interesting to know when they were collected and when the informants had learned them. Also missing in his original publication were the tunes. But in fact he had noted melodies for these pieces. Charles K. Wolfe was able to utilize Talley's notebooks and include the relevant tunes in the new edition published in 1991. Strangely the one for the "Temperance Rhyme" (no. 324, p. 174) is completely different and doesn't belong to our tune family while the melody added to "I'll Eat When I'm Hungry" (No. 167, p. 97) is not the simple form á la Perrow, Lomax and Randolph. Instead its structure is a-a'-b-a' . The a-parts are very similar to Randolph's and Perrow's variants. But with its more sophisticated form it is closer to the variants from the 19th century like "The Noble Skew Ball" and "John Adkin's Farewell" although the middle-part is different from these songs. This particular tune would be more fitting to the "Temperance Rhyme" with its four lines per verse than to "I'll Eat When I'm Hungry":

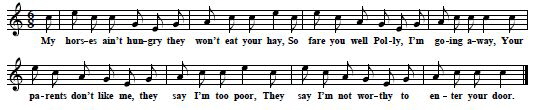

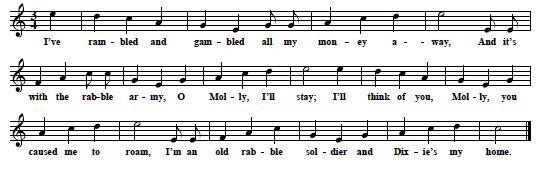

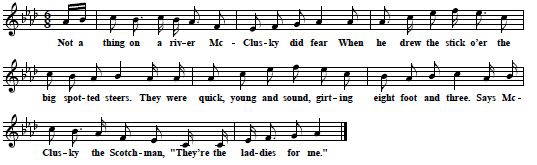

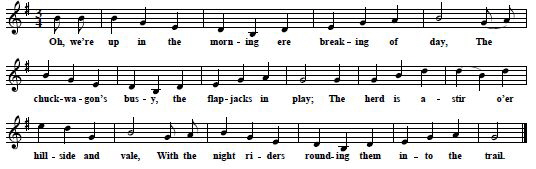

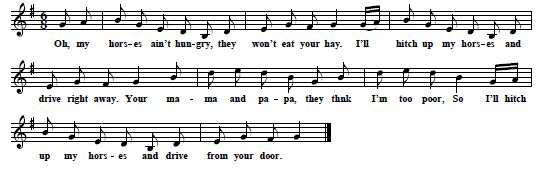

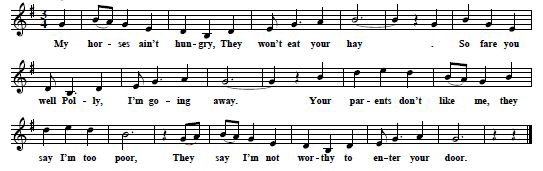

At this point we have five variants of our tune that were collected during the first two decades of the 20th century. They were all used for a rather unstable drinking song. But that is not much and one may assume that this particular song was at that time simply on the way to oblivion until it was saved for posterity by the collectors. Since the mid-20s a new source for these kind of songs came to the fore. The recording industry discovered so-called "old-time music" and helped spread this genre far and wide. At first the recording artists used songs from their original repertoire but because of the great demand they quickly had to make themselves familiar with new material with the help of the song collectors' publications. Lomax' Cowboy Songs were apparently especially popular in this respect. Or else they wrote more or less new "old" songs. There was also a lively interaction between the sphere of commercial recordings and what is called "oral tradition" that has rarely been discussed by folklorists. The people not only listened to all these new records they also adopted them into their own repertoire them and occasionally even passed them off as "old songs" to inquiring folklorists. Fiddlin' John Carson was responsible for the first recorded " Hillbilly"-version of a tune from the song family discussed here. In February 1926 his record label brought out "Drunkard's Hiccups" (Okeh 45032; see Russell, p. 176; see also The Bluegrass Messengers), a raucous fiddle tune. I couldn't find a free mp3 but it is easily available at amazon. This song includes the well known couplet "I'll eat when I'm hungry, I'll drink when I'm dry" but also a verse we already know from Emma Miles' version from Tennessee ("I tune up my fiddle [...]"): The worst kind of people are begging to know, Much more interesting for the subsequent history of our tune family was "My Horses Ain't Hungry", for once not a song about drinking and card-playing but a nice love-story. It was first recorded by Kelly Harrell, "a country balladeer with a golden voice" (Richard Mattheson, Bluegrass Messengers) in June 1926, accompanied by an unknown fiddle-player and Carson Robison on guitar (Victor 20103, see Russell, p.403; mp3). In April 1927 Vernon Dalhart, also "probably" accompanied by Carson Robison - his partner at that time - recorded his version of this song and in 1930 text and tune were published in Robison's songbook The World's Greatest Collection Of Mountain Ballads and Old Time Songs (p. 32):