|

" Treu und herzinniglich, Robin Adair"

A British Tune In Germany

Introduction

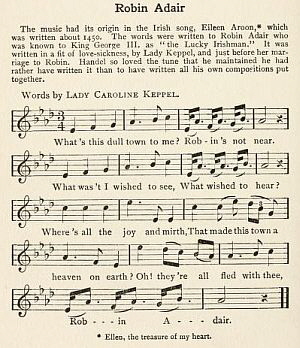

A while ago I started researching a song family that is nowadays usually represented by "Eileen Aroon". Here is for reference the tune and one verse of the version that is best known these days. In fact I heard it first this way:

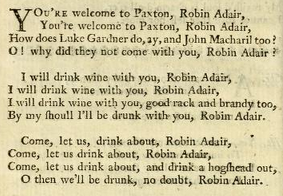

This group of songs can be traced back to the early 18th century and includes variants with quite different lyrics and sometimes also music (see my attempt at a Chronological List [CL]). Among them is a song called "Robin Adair" that seems to have been one of the most popular hits of the 19th century both in Britain and in the USA. It was first introduced to English audiences by singer John Braham in 1811 and then published as sheet music by numerous music sellers. Here is for example an edition from Liverpool (1812). It names not only Braham but also Scottish singer John Sinclair, one of the many artists who at that time started to perform this popular hit:

![2. Title page of sheet music: Robin Adair. The much admired Ballad as Sung by Mr. Braham at the Lyceum, and Mr. Sinclair at the Theatre Royal Liverpool, With an Accompaniment for the Piano Forte or Harp, Liverpool, Printed by Hime & Son Castle Street & Church Street, n. d. [after 1811] 2. Title page of sheet music: Robin Adair. The much admired Ballad as Sung by Mr. Braham at the Lyceum, and Mr. Sinclair at the Theatre Royal Liverpool, With an Accompaniment for the Piano Forte or Harp, Liverpool, Printed by Hime & Son Castle Street & Church Street, n. d. [after 1811]](../assets/images/autogen/RA-Sincl-Hime-c.png) |

This "Robin Adair" was then reprinted regularly in countless publications on both sides of the ocean over the next hundred years .We can find it for example in Helen K. Johnson's influential Our Familiar Songs (New York 1889, pp. 355-7) or in the appropriately titled collection Songs Every Child Should Know. A Selection Of The Best Songs Of All Nations For Young People by Dolores M. Bacon (New York 1907, p. 70, both available at the Internet Archive). The tune is identical to today's "Eileen Aroon":

|

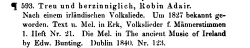

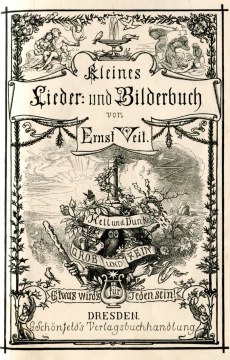

But interestingly the song was equally popular in Germany during the 19th and early 20th century. It is listed more than 70 times in Hofmeister's Musikalisch-Literarischen Monatsberichten between 1829 and 1900 (found via the database Hofmeister XIX) but even that number is far from complete. I came across half a dozen translations - or better adaptations - of which one became particularly widespread. The German "Robin Adair" can be also found in numerous songbooks. One of many examples is the second edition of August Härtel's Deutsches Liederlexikon, according to the subtitle a "collection of the German people's best and most popular songs and chants". This weighty tome was published in Leipzig 1867 (No. 762, p. 597):

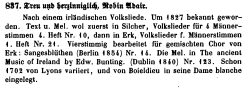

About 40 years later it appeared in a book called Deutsche Lieder. Aus alter und neuer Zeit (c. 1900-1910, p. 195):

In the first book the song was identified as "Scottish" and in the second one as "Irisches Volkslied". Apparently the editors were sometimes divided about its origin. But these hints as well as the reference to Boieldieu's popular opera La Dame Blanche can serve as helpful starting-points for further research. These example clearly suggest that the German "Robin Adair" was no mayfly but for a considerable time a part of the common song repertoire.

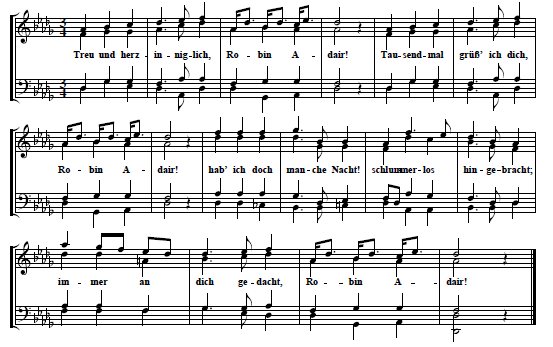

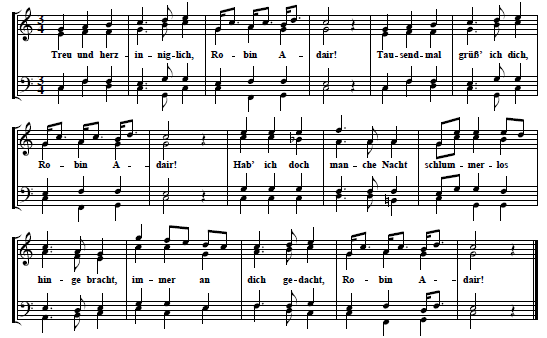

This piece also became a standard for German Männergesangvereine - male choirs - and at least half a dozen different four-part arrangements were published during the 19th century. Here is for example a version by Wilhelm Greef, choirmaster and seminary teacher in the town of Moers. It was first published in 1854 in the 9th booklet of his popular series Männerlieder, alte und neue, für Freunde des mehrstimmigen Männergesanges (here 6th ed., 1869, No. 21, p. 25, at the Internet Archive) :

Other important and influential arrangers like Friedrich Silcher and Ludwig Erk also took care of the song and and even today it is still performed by male choirs, as can be seen in a video recorded in 2012 that is available at YouTube.

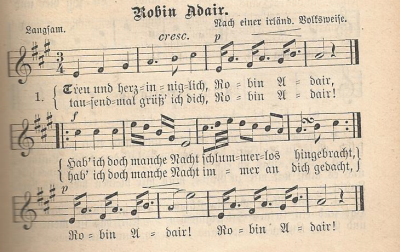

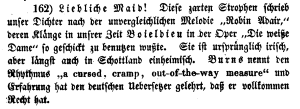

The tune was also sung with different texts. One was called "Heut' muß geschieden sein". This variant can be found for example in a songbook for schools with the title Deutsches Jugendliederbuch für höhere Lehranstalten, a popular collection compiled by Bavarian music teacher and composer Simon Breu that was first published in 1908 and then regularly reprinted (here from the 11th ed., 1923, Nr. 68, p. 64).

This looks like a fascinating story and in fact it was. The following text is a first attempt at untangling the German history of "Robin Adair". As usual it became much larger than I had first expected. The sheer number of relevant publications was somewhat surprising. But also felt it necessary to discuss some important topics, especially the early history of the Volkslied in Germany. I often had to use the German term, simply because it was defined quite different from the current English term "folk song" but instead had much wider connotations.

But at first it is helpful to return to the British Isles and give a short overview of the history and development of "Eileen Aroon" and "Robin Adair" in Ireland, Scotland and England from the first available printed version in 1729 up to the year 1826 when the tune was introduced in Germany. This is of course not the complete story of this song family. A more detailed account can be found in my Chronological List and here I will only mention the most important stepping-stones.

I. "Aileen Aroon" & "Robin Adair" in Britain 1729 - 1826

We know neither how old this tune is nor the name of its composer. There have been attempts to attribute the original "Eibhlin-a-ruin" to one Carroll O'Daly (or Gerald O'Daly or Cerbhall Ó Dálaigh). According to an "anecdote" from the repertoire of the Irish harper Cormac Common (1703-c.1790) - first published by Joseph C. Walker in 1786 in the Historical Memoirs Of The Irish Bards - he had written it "two centuries ago" for a lady by the name of Elinor Kavanagh (Appendix, p. 60, at the Internet Archive):

"A man of Cormac's turn of mind must be much gratified with anecdotes of the music and poetry of his country. As he seldom forgets any relation that pleases him, his memory teems with such anecdotes. One of these, respecting the justly celebrated song of Eibhlin-a-ruin, the reader will not, I am sure, be displeased to find here. Carroll O'Daly[...], brother to Donough More O'Daly, a man of much consequence in Connaught about two centuries ago, paid his addresses to Miss Elinor Kavanagh. The lady received him favourably, and at length was induced to promise him her hand. But the match, for some reason now forgotten, was broken off, and another gentleman was chosen as a husband for the fair Elinor. Of this, Carroll, who was still the fond lover, received information. Disguising himself as a Jugleur or Gleeman he hastened to her father's house, which he found filled with guests, who were invited to the wedding. Having amused the company a while with some tricks of legerdemain, he took up his harp, and played and sung the song of Eibhlin A Ruin, which he had composed for the occasion. This, and a private sign, discovered him to his mistress. The flame which he had lighted in her breast, and which her friends had in vain endeavoured to smother, now glowed afresh, and she determined to reward so faithful a lover. To do this but one method now remained, and that was an immediate elopement with him: this she effected by contriving to inebriate her father and all his guests".

This story was revived in 1812 in Matthew Weld Hartstonge's Minstrelsy of Erin (pp. 168-9) and from then on regularly recycled in all kinds of publications, for example the influential Gentleman's Magazine (Vol. 97, 1827: January, p. 60). James Hardiman included the tale his Irish Minstrelsy (1831, Vol. 1, p. 356) but claimed that it all had happened much earlier, maybe in the 13th century. In 1861 the Illustrated Dublin Journal (pp. 182-184) published a much embellished version with the title "O'Daly's Bride". Later S. J. Adair-Fitzgerald reanimated the original anecdote in his Stories Of Famous Songs (1898, p. 16) but told his readers it was a "true story" while William Grattan Flood in the Story Of The Irish Harp (1905, p. 62; see also his article in Grove's Dictionary, 2nd ed., Vol. 1, 1911, pp. 770-1) even claimed to know the exact year: "'Eibhlin a Ruin' [...] was composed in 1386 by Carrol O'Daly, a famous Irish harper". In fact there had been a couple of "real" poets by the name of Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh since the middle ages and Grattan Flood simply tried to associate one of them with this song. But this was of course pure fantasy.

The principle behind these tales was simply: the older the better. But it would be too easy to dismiss them as a forgeries. What was first clearly marked as an anecdote became a "true story" only during the 19th century when "Robin Adair" was a great hit. It could then be used as the proof that the tune was originally from Ireland and that the Scots had stolen it from the Irish. Moreover the song now acquired authenticity as well as an historical context and could be associated with a legendary Irish poet. In fact this legend became indelibly linked to "Eileen Aroon" and one may say that it is now an essential part of the song (for a more thorough discussion of this problem see CL 035)

The very first real evidence for the existence of this tune dates from the year 1729. Playwright Charles Coffey included a melody with the title "Ellen A Roon" in The Beggar's Wedding. John Gay's Beggar's Opera had been a great success the year before and "there was a rage for these ballad operas [...] between 1728 and 1733" (Kidson, p. 102). Coffey was among the first to jump on the bandwagon. The premiere in Dublin was on March 24th at Smock Alley but it seems it was a failure there. Only two more performances are documented. In London "The Beggar's Wedding" was first staged on May 29th at the New Haymarket Theatre and there it was much more successful: 35 performances are known (see Boydell, p. 45; London Stage 2.2, p. 1036; London Stage 3.1, p. cxxxix). Coffey used the tune in the 3rd act as "Air XVII" (2nd ed., p. 63; Air XVIII since the third edition):

The first two editions did not include the music. But for the third edition he added an appendix with all the tunes (ESTC N033008, ECCO). Interestingly the B-part looks quite different from the version of the melody known today. It's is not clear if this particular variant was common at that time or if Coffey himself had edited the tune (reprinted in Moffat 1898, p. 338; also SITM 600, p. 52):

|

Apparently this version of "Ellen A Roon" didn't have much influence and to my knowledge it never appeared again. The same can be said about a variant with another different B-part that was included in the third edition of printer John Walsh's Second Book of the Compleat Country Dancing-Master (ca. 1735/6, "Ellin a Roon", p. 18; online available at IMSLP). It was not until 1741/2 that the song reached a wider audience. Kitty Clive (1711-1785) - a very popular actress and singer (see BDA 3, pp. 341-362) - learned a version with Gaelic text while in Dublin, according to a magazine "in Compliment to the Irish Ladies and Gentleman, for the Civilities which she hath received". Her very first performance of "the celebrated Song called Ellen a Roon" seems to have been on August 19th that year (from Boydell, p. 72-3). The following year she also started to sing this piece in London. The debut was on March 8th, 1742 after the third act of the comedy The Man Of Mode at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane (London Stage 3.2, p. 974):

"The celebrated Irish Ballad Elin a Roon, sung by Mrs. Clive in Irish, as she perform'd it at the Theatre Royal in Dublin".

She sang the song again a couple of times during the next months, once for example "at the particular desire of several ladies of quality" (London Stage 3.2, p. 977) and it seems it was one of the greatest hits of the season. Her version was also published as sheet music :

- Aileen Aroon, An Irish ballad. Sung by Mrs. Clive at ye. Theatre Royal, n. p., n. d. [ca. 1742] (see Copac, facsimile reprint in Maunder 1993, p. 449)

It is not that difficult to see that in this variant the B-part is much closer to the current version of the song than in Coffey's version. But it is five bars longer (measures 13 - 17). Of course it is not possible to say if this was the original form of the tune:

![9. Tune & text (first verse only) from: The celebrated Irish Ballad Elin a Roon, sung by Mrs. Clive in Irish, as she perform'd it at the Theatre Royal in Dublin, n. d. [1742?] 9. Tune & text (first verse only) from: The celebrated Irish Ballad Elin a Roon, sung by Mrs. Clive in Irish, as she perform'd it at the Theatre Royal in Dublin, n. d. [1742?]](../assets/images/autogen/AA-Clive-1741.png) |

Nonetheless Kitty Clive's version became a standard for the next 50 years. Other singers and instrumentalists added "Aileen Aroon" to their repertoire (see f. ex. Boydell, p. 299) and it was regularly performed on stage both in Ireland and England, for example by Welsh harper John Parry in 1757 and later also by popular singers like G. F. Tenducci, Gasparo Savoi, Elizabeth Linley, Ann Catley and Michael Leoni (see CL, Nos. 012, 019, 020, 027, 032). The tune can be found in Burke Thumoth's Twelve Scotch And Twelve Irish Airs (London 1745, No. 13, pp. 26-7, see also YouTube), Matthew Dubourg wrote variations (1746, reprinted in The Monthly Melody, c. 1760, pp. 34-5; see Boydell, p. 109), James Oswald included it 1755 in the fifth volume of his Caledonian Pocket Companion (No. 21), Scottish publisher Robert Bremner used a simple arrangement for the "English guittar" in his Instructions for this instrument (Edinburgh, c. 1758, p. 21, pdf available on Rob McKillop's website) and shortly before the turn of the century the tune was recycled once again by James Aird in his Selection Of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs (Vol. V, No. 72, p. 29, from a later edition of Vol. 5 & 6, 1801). Not at least this melody was borrowed for a considerable number of new songs, for example for two verses of "The Roast Beef Of Old England", a "cantata" based on William Hogarth's painting The Gate of Calais (1750s, see CL, No. 008) or for another of these kind of cantatas, "The Courtship" by one George Rollos (1760, see, CL, No. 015). But of course this was common practice at that time.

Towards the end of the 18th century a certain antiquarian interest for this old song arose. I have already mentioned Joseph Walker's Historical Memoirs Of The Irish Bards (1786). In 1792 Edward Bunting (1773-1843) was hired to write down the music performed at the Belfast Harper's Festival. Among the harpists playing there was Dennis Hempson (1695-1807) from Magilligan. Later that year he visited Hempson at home and collected his version of "Elen A Roon". This tune can be found in one of his notebooks, a "Book of Irish Airs" started "in the year 1792 and finished in 1805", that is now available online on the website of the Queen's University, Belfast (see MS4/29/064 , Queen's Special Collections; see also O'Sullivan 1983, No. 123, pp. 175-6, also SITM No. 6038, p. 1099). Bunting only published this variant in 1840 in the third volume of his Ancient Music of Ireland in a piano arrangement and claimed that in "this setting" the song was "restored to its original simplicity" (sic!; p. 90; No. 123, p. 94). Here is the melody line of the first 20 bars:

|

This variant is clearly related to the one used by Kitty Clive 50 years earlier. According to Bunting these "variations" had been written in 1702 by Cornelius Lyons, "harper to the Earl of Antrim [...] another of Carolan's [(1670 - 1738)] contemporaries" (dto., p. 70). I assume he had received this information from Mr. Hempson. Of course there is no way to prove this claim. But interestingly another reference to this particular harper suggests that there might be some truth to it. The MacLean-Clephane Manuscript, a Scottish music collection from around 1800 includes a number of "harp airs". These had apparently been "taken from the playing" of another Irish harper by the name of O'Kain. Among them is an interesting version of "Elan A Rún", that was - according to an accompanying note - "improved by Lyons and O'Kain's prescription á Dubourg, an Irish fiddler" (see SITM No. 3712, p. 675). So perhaps Mr. Lyons really had a hand in the transmission of the tune and maybe some variant of it already existed around 1700. This is not unlikely but without other supporting evidence it remains a speculation.

What we know is that "Aileen Aroon" - or "Ellen a Roon" - was very popular in England since the early 1740s. But at the same time there existed in Scotland a rather obscure song with the title "Robin Adair" that was sung to a closely related tune. The earliest evidence for this piece can be found in a Scottish keyboard manuscript apparently started in 1739, the music book of one Elizabeth Young. (NLS MS 5.2.23, in Early Music Vol. 2, Reel 3, tune also in SITM No. 849, p. 156]:

|

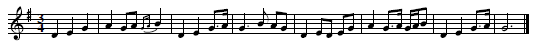

Unfortunately this is only the first half of the song: the B-part is missing. At least this version shows that the tune was known in Scotland already at that time and that it was associated with the song called "Robin Adair". But we can also see that this Scottish variant was not simply an offspring of Kitty Clive's popular hit but was known there before her "Aileen Aroon" was published. A text for "Robin Adair" came to light only 25 years later when it was included in some songsters, for example in The Lark, according to the subtitle a "Select Collection Of The Most Celebrated And Newest Songs, Scots and English" (Vol. 1, Edinburgh 1765, p. 268). It was a simple drinking song. But of course it is not clear if this were the original Scottish words for the tune.

|

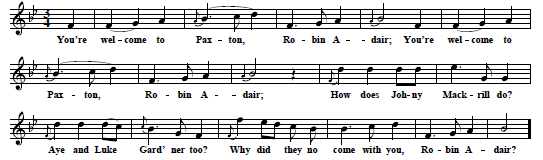

At around the same time David Herd collected a fragment of two verses that he didn't use for his Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1776, see Hecht 1904, pp. 275, 334/5). But only in 1793 a complete tune with four verses was published. It can be found in the second volume of David Sime's Edinburgh Musical Miscellany. A Collection Of The Most Approved Scotch, English, And Irish Songs, Set To Music (Song CXXX, pp. 304/5) :

Not much is known about Mr. Sime. He was a musician and teacher in Edinburgh and died in 1807 (see Brown/Stratton, p. 373). But apparently this publication was very successful. A year later the second volume was reprinted as The New Edinburgh Musical Miscellany (ESTC T301078, ECCO) and in 1804 respectively 1808 a second edition of the complete work came out (see Copac). As the subtitle say this was not only a collection of Scottish songs but the editor also did include English and Irish pieces as well as current hits by "Dibdin, Hook, and other celebrated composers". These books were clearly not intended as an antiquarian publication but as a handy compilation of songs both old and new that were popular at that time.

|

The tune used by Sime looks like a simplified and abbreviated version of the variant made popular by Kitty Clive. The B-part is five bars shorter. Measures 13-17 are missing. Even though Sime's collection was published more than 50 years after Mrs. Clive's "Aileen Aroon" there is still a certain possibility that his version is closer to the original form of the song. Interestingly we know a couple of English and Scottish songs from the 17th century with exactly the same meter and structure as "Robin Adair" even though they were sung to different tunes. One of them is "Franklin Is Fled Away (O Hone, O Hone)" a ballad apparently first published in the 1650s (see Simpson, pp. 233-5, Chapell 1855, p. 370; text f. ex.: Pepys 2.76 at EBBA):

Franklin, my loyal friend,

O hone, O hone!

In whom my joys do end,

O hone, o hone!

Franklin my heart's delight,

Since last he took his flight,

Bids now the world good-night,

O hone, O hone.

[...]

Here even the internal refrain is applied in the same way as in "Aileen Aroon" and "Robin Adair". Another song from this group is "Wellady". It seems that a tune of this name was known since the 1560s. Later it was used for example for a ballad about the execution of the Earl of Essex in 1601 (see Chappell 1855, p. 174-5, Simpson, p. 747; HEH Britwell 18290 at EBBA):

Sweet Englands pride is gon,

Welladay, welladay,

Which makes her sigh and grone

Evermore still:

He did her fame advance,

In Ireland, Spaine, and France ,

And now by dismall chance,

Is from her tane.

[...]

A Scottish example is "Mournful Melphomene", a ballad about Princess Elizabeth, who had died at the age of 14 in 1650. The first broadside with the text was published shortly afterwards (see f. ex.: Roxburghe 3.42, at EBBA):

Mournful Melpomene,

Assist my quill,

That I may pensively

Now make my will;

Guide thou my hand to write,

And senses to indite,

A Lady's last goodnight:

Oh! Pity Me

[...]

According to this broadside the original tune for the song was "O Hone, O Hone" (i. e. "Franklin Has Fled Away"). In 1779 the text was reprinted in a book called The True Loyalist; or, Chevalier's Favourite (pp. 65-72 , ESTC T114471, ECCO) and there "Robin Adair" was in fact indicated as the tune. Another Scottish song from this group is "Cromlet's Lilt". We can find the the text with what was possibly the original melody in the second volume of William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius (1733, No. I, p. 1):

Since all thy vows, false Maid,

Are blown to Air,

And my poor Heart betray'd,

To sad Despair,

Into some wilderness,

My grief I will express,

And thy Hard-heartedness,

O cruel Fair.

[...]

It is clear to see that all these songs were built on the same pattern. Melodies and lyrics are interchangeable and one can sing any of these texts to every one of these tunes. It strikes me as very odd that the relation of "Aileen Aroon" and "Robin Adair" to this group of ballads has never been addressed. They all - but especially "Franklin Has Fled Away" - could have easily been used as a model and blueprint by the anonymous creator - whoever that was - of the very first exponent of the song family discussed here. It is not unlikely that "Aileen Aroon", "Robin Adair" - or perhaps a common ancestor - started out as a local Irish or Scottish variant of "Franklin" and/or "Welladay". This approach would also help to place this hypothetical original version safely into the second half of the 17th century, exactly the time when the other pieces mentioned here were all easily available. But at least the popularity of this particular form strongly suggests that the shorter version of the tune á la Sime could be closer to how the song originally looked like than the extended variant learned by Kitty Clive in Dublin half a century before the publication of the Edinburgh Musical Miscellany.

It is also easy to see that the tune of "Robin Adair" is nearly identical to the one used for today's "Eileen Aroon". In fact Sime's collection played a key role in the further history of this song family because his variant of the melody would quickly replace Kitty Clive's version as the standard form of the tune. Mostly responsible for this development were Robert Burns, George Thomson and Thomas Moore.

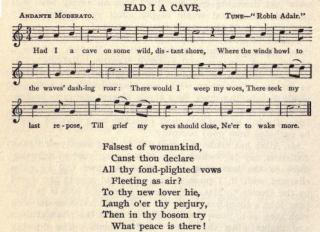

Burns (the following summarized from CL, Nr. 042) experimented with this tune in 1793 and created three new sets of lyrics: "Phillis The Fair", "Had I A Cave" & "Address To General Dumourier" (see Dick 1903, pp. 5, 45, 247, 352, 366, 456). It's not clear if Burns had learned this "crinkum-crankum tune" from Sime's book or if he was already familiar with it. Interestingly in the second letter to Thomson he noted that he had "met with a musical Highlander [who] well remembers his mother singing Gaelic songs to both 'Robin Adair' and 'Gramachree'" (Lockhart, No. XXXIII, p. 404). But he started creating these lyrics only in 1793, exactly the year that the Edinburgh Musical Miscellany came out and his texts were clearly written to this variant of the tune. For reasons I do not understand both James Dick (1903) and Donald Low (1993, No. 239, 240, pp. 616-19) in their editions of the Songs of Robert Burns decided to use "Aileen A Roon" from James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion (V, 21) for their setting of these songs. Of course that doesn't sound right. As already mentioned Oswald's variant had been derived from Kitty Clive's extended Irish version and they had to mutilate that tune a little bit. Here is "Had I A Cave", but with the correct form of the melody, from George Gebbie's Complete Works of Robert Burns (1886 ,1909, p. 204):

|

Burns' three new texts were all published posthumously and only "Had I A Cave" became a popular song in its own right. The first one to use this text was George Thomson, who included it in his Select Collection Of Original Scottish Airs. During the late 18th and early 19th century there was a great interest in Scottish songs. A considerable amount of relevant collections were published, sometimes as handy volumes with texts, tunes and a thorough bass like James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) but also as lavish productions with modern arrangements by eminent European composers like Pleyel, Haydn and even Beethoven. Thomson - clerk in Edinburgh and part-time publisher - was responsible for the most ambitious of these projects. It ran for over 50 years. One can't say that his publications were particularly popular among later experts for Scottish music. In fact he was often criticized heavily and even derided for his efforts (for the background see Fiske 1983, pp. 55-79, McCue 2002 & 2003, Will 2012). But the criticism often missed the point. Thomson had a different idea of "authenticity". He was interested in the tunes and therefore it was no problem for him to dress them in new arrangements by the best musicians available at that time and - if necessary - replace the old texts with new lyrics by contemporary poets like Burns.

"Robin Adair" was first published in 1799 in the "Fourth Set" of 25 songs (No. 92) and then 1801 in a new edition where Thomson combined the first four sets to two volumes of 50 songs each (here Vol. 2, No. 92):

Of course he discarded the old text. A profane drinking song surely wasn't up to his standards. Instead he preferred Burns' "Had I A Cave". The tune was clearly borrowed from Sime's Edinburgh Musical Miscellany. Thomson kept most of grace notes of that version as well as the upbeat note before the first measure. The arrangement - for two voices, cembalo, violin and violoncello - was written by popular Austrian composer Ignaz Pleyel. This version was later reprinted for example in a collection called The Beauties Of Melody (London 1827, p. 155-6, at The Internet Archive) and is now available in a modern edition of all of Pleyel's works for Thomson (Rycroft 2007, Vol. 2, No. 22, p. 32).

But apparently Mr. Thomson wasn't completely satisfied with this arrangement and he commissioned a new one from Joseph Haydn - also a duet - that was then published in a revised edition of this volume in 1803 (No. 92; see Rycroft 2001, pp. 198-9; a manuscript is available online at the BnF):

In 1815 Thomson ordered another new arrangement from Ludwig van Beethoven but for some reason never used it. That version was only published much later - in the 1860s - in Germany (see chapter VI). Instead he stayed with Haydn's work that appeared again in later editions, for example one from around 1822 (No. 92, at BStB-DS) and also in the first volume of the less costly octavo edition (1822-3, No. 45, at the Internet Archive, see McCue 2003, pp. 114-5). Interestingly here we also find as an alternate text six verses of "an old song for the same air". This was in fact "Cromlet's Lilt", as already noted a closely related piece with exactly the same structure and meter:

Thomson's collection may not have been a particularly great success but it established Burns' new words as one of the standard texts for this tune. But I must admit that I am somewhat irritated that "Robin Adair" wasn't included in any of the other editions of Scottish songs from this era. It was a surprising omission in the Scots Musical Museum even though Burns was heavily involved in that project. Nor can it be found in the collections published for example by William Napier, Pietro Urbani or William Whyte. But instead this tune variant "returned" to Ireland with the help of Thomas Moore and Sir John Stevenson. The year 1808 saw the publication of the first volume of their Selection of Irish Melodies and among the songs included was "Erin, The Tear And The Smile In Thine Eyes" (pp. 14-19, available at the Internet Archive):

![15. "Erin, The Tear And The Smile In Thine Eyes", text & tune from: A Selection of Irish Melodies, with Symphonies and Accompaniments by Sir John Stevenson, Mus. Doc, and Characteristic words by Thomas Moore, Esq, Dublin, n. d. [1807], p. 12 15. "Erin, The Tear And The Smile In Thine Eyes", text & tune from: A Selection of Irish Melodies, with Symphonies and Accompaniments by Sir John Stevenson, Mus. Doc, and Characteristic words by Thomas Moore, Esq, Dublin, n. d. [1807], p. 12](../assets/images/autogen/Erin-Moore-1807.png) |

Erin! the tear and the smile in thine eyes

Blend like the rainbow that hangs in thy skies!

Shining through sorrow's stream,

Saddening through pleasure's beam,

Thy sons, with doubtful gleam,

Weep while they rise!

Erin! thy silent tear never shall cease,

Erin! thy languid smile ne'er shall increase,

Till, like the rainbow's light,

Thy various tints unite,

And form, in Heaven's sight,

One arch of peace!

It is a little bit surprising that Moore and Stevenson didn't use the well-known older version of the tune that had been so popular during the 18th century. But for some reason they resorted to the simpler Scottish variant. Nonetheless they listed this "air" with the title "Aileen Aroon". Veronica ní Chinnéide in an article about The Sources of Moore's Melodies (1959, p. 118) suggests that they had taken the melody from Thomson's collection but of course it could have also been lifted directly from the Edinburgh Musical Miscellany. The latter seems to me more likely, because just like Sime they used the key of 'Bb' while Thomson's versions are in 'C'. At this point the very same variant of this tune was identified both as "Scottish" and as "Irish". It always depended on the source. Later all the Irish poets who tried their hand at new words for "Eileen Aroon" always used this version of the melody. Moore had set an example and writers like John Banim, Gerald Griffin or Thomas Davis (see CL, B14-16) followed him in this regard.

The 1810s saw more attempts at recycling this tune with the help of new lyrics. One example was a song called "Now Is The Spell-Working Hour Of The Night". That piece can be found for example in Crosby's Irish Musical Repository (1808, pp. 272-3, at the Internet Archive). But apparently it wasn't particularly successful and sank without much traces. Much more important was the new "Robin Adair" introduced by singer John Braham in 1811. Braham (see Wikipedia; BDA 2, pp. 291-303), one of the greatest singing stars of that era, performed it first on December 7th that year at a concert at the Lyceum, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Two days later the Morning Post (9.12.1811, p. 3, at BNA) published a glowing review:

"[...] To many of the songs he [Braham] gave an effect which perfectly astonished us, and the frequent encores with which he was honoured, bore simple testimony to the taste, and to the gratification of the audience. He introduced the ballad of 'Robin Adair,' which he sung with exquisite feeling, and with all that simplicity of manner which is necessary to render it perfect justice. The audience were absolutely in raptures with it. It was tumultously encored, and loudly called for a third time. The last call was not complied with. It was certainly not necessary, as from the impression it made, being sung but twice, it is probable that the last two lines will often be repeated by many of those who were present -

'Oh! I shall ne'er forget/Robin Adair.'"

The sheet music came out a week later as can be seen from an ad in the Morning Post from December 14th (p. 1, available at BNA):

- Robin Adair. The Much Admired Ballad Sung With Enthusiastic Applause By Mr. Braham At The Lyceum Theatre, The Symphony & Accompaniments Composed & Arranged For The Harp Or Piano Forte by W. Reeve, Button & Whitaker, London 1811/12 (see Copac; pdf of original sheet music from my collection, now also at the Internet Archive; this is an unofficial second edition printed since late in December '11 or early January '12. It includes on the cover a letter by Mr. Reeve to all local newspapers warning against "spurious copies" of this song by competing publishers; see in my blog: John Braham's "Robin Adair" (1811) - The Original Sheet Music)

Reeve (1757-1815, see New Grove, 2nd ed., p. 75) was an organist and popular composer who apparently knew what was commercially viable. But it is not clear how much he was involved in the creation of this new version besides writing the accompaniment and the instrumental parts:

What's this dull town to me,

Robin's not near.

What was't I wish'd to see,

What wish'd to hear;

Where all the joy and mirth,

Made this town heaven on earth,

Oh, they're all fled with thee,

Robin Adair.

What made th' assembly shine,

Robin Adair.

What made the ball so fine,

Robin was there.

What when the play was o'er

What made my heart so sore.

Oh, it was parting with

Robin Adair.

But now thou'rt cold to me,

Robin Adair,

But now thou'rt cold to me,

Robin Adair.

Yet he I loved so well

Still in my heart shall dwell,

Oh, I can ne'er forget,

Robin Adair.

The tune was of course derived - directly or indirectly - from the variant published by Sime. But there were some interesting changes. Most important are the eighth-notes in the third, seventh and sixteenth bar. This kind of acciaccatura has been called the "Scotch Snap" (see Grove 3, 1883, p. 139). Measure 10 also looks a little bit different. Here the melody line goes up to the f'' and then an octave down to the f'. In all the other versions the interval was not that great and it only went down from an eb'' to the g'. I am not sure if this was done on purpose or if it simply was an error by the printer. For my ears this particular phrase sounds more wrong than right. But at least this variation helps to determine if later versions of this tune were directly derived from the original sheet music. Besides that there are also some more minor variations and ornamentations, especially the triplet in measure 11 that is also a distinguishing mark of this variant.

The new text is of course strikingly different from the one of the first "Robin Adair". The old drinking song may have looked a little bit too old-fashioned at that time. We don't know who was responsible for this new set of words. It could have been Braham himself or some anonymous street- or tavern-poet from whom he had bought this piece. But at least it should be noted here that it surely wasn't Lady Carolina Keppel (1734-1768) who has often been associated with the song. According to an immensely popular legend she is said to have written it ca. 1757 because her illustrious family didn't allow her to marry one Robert Adair (c. 1715-1790), an Irish surgeon. Here is a version of the story that was printed in the Canadian newspaper Family Herald And Weekly Star in the 1890s (Old Favourites, p. 59):

:

This of course sounds highly suspicious and extremely unlikely. In fact this fairy-tale was fabricated only in 1864 - more than 50 years after Braham had introduced the song - by one William Pinkerton in an article in the magazine Notes & Queries (pp. 500-504). Even though Mr. Pinkerton wasn't able to prove his claims the story quickly won widespread popularity and was regularly recycled, often in embellished versions and usually without acknowledging Pinkerton's article. Typical examples can be found for example in Charles Bombaugh's Gleanings For The Curious (1890, p. 805), in the Random Sketches On Scottish Subjects by John D. Ross (1896, pp. 51-7) or Lady Russell's The Rose Goddess and Other Sketches Of Mystery & Romance (1910, pp. 87-91).

For some reason this legend was sometimes even promoted by serious researchers and Lady Keppel's name found its way into many songbooks and some library catalogs. But this story is too good to be dismissed as a simple fake or an example for bad research. As in the case of "Aileen Aroon" and Cearbhall O'Dalaigh it became an integral part of the song. A legend like this is of course always much more interesting than the simple truth. It has turned a profane popular hit into a ballad presumably created by a real person who even happened to be a member of the nobility.

We may not know the writer of this text but interestingly there is some evidence for its real historical background. Irish poet Gerald Griffin (1803-1840) later noted that the song is "supposed to refer to the attachment of the then Prince of Wales to Mrs. Fitzherbert". This suggestion can be found in "The Foreman's Tale - Sigismund", the first story in his posthumously published Tales Of The Jury Room (1842, p. 131; see Wikipedia about Maria Fitzherbert). In fact that was the most popular scandal at the time the new "Robin Adair" was introduced and the new lyrics fit perfectly well to this particular affair. I am not aware of any other evidence for this assumption. But it sounds not unreasonable and not at least it helps to explain why the song became so immensely popular. This is the kind of real background story that everybody surely knew about in 1811 and it would not have been too difficult to understand the allusion to the Prince of Wales and his not so secret wife.

But no matter who really wrote this text and what it may have been all about, John Braham's performance turned the song into a big popular "hit". According to a report in the Metropolitan Magazine in 1837 (p. 136) "the publisher sold, (for Braham's profit,) in one year, for home consumption and exportation, upwards of two hundred thousands copies". Of course other popular artists quickly added "Robin Adair" to their repertoire and were anxious to throw their own version of this ballad on the market to get a slice of the cake. A reviewer in the Repository Of Arts, Literature, Commerce etc noted in April 1812 (p. 228-9):

"The revival of the old ballad of " Robin Adair" (now the rage in the musical world), is due to Mr. Braham. His unparalleled vocal powers have given new interest to an air which, of itself, possessed the merit of beautiful simplicity. No wonder, then, if the success of the song has roused the industry of a number of composers to run, as it were, a race, who should furnish tho most popular production founded on this elegant theme. Not only the song itself has been harmonized by several hands, but it has received a variety of dressings, in the shape of allegretto, rondo, variations, &c."

In a short time a considerable number of well-known musicians and their publishers had jumped on the band![18. Review of sheet music: Robin Adair. A Simple Irish Ballad, by J. Mazzinghi, Goulding & Co. [1812], in: Monthly Magazine And British Register, Vol. 33, 1812, No. 224, March 1, p. 166 18. Review of sheet music: Robin Adair. A Simple Irish Ballad, by J. Mazzinghi, Goulding & Co. [1812], in: Monthly Magazine And British Register, Vol. 33, 1812, No. 224, March 1, p. 166](../assets/images/autogen/RA-reviewMM-Mazz.png) -wagon and new arrangements were for example published by Joseph Mazzinghi, John Parry, Antony Corri, Thomas Howell, William Ling and Charles Stokes (see more reviews in Repository of Arts, Literature, Vol. 7, 1812, p. 288; The Monthly Magazine, 1812, Vol. 33, pp. 53, 166; Vol. 34, pp. 155, 445) as well as Anne-Marie Krumpholtz (see Copac and the Internet Archive) and Sophia Dussek (see Copac, online at Hathi Trust). Of particular interest and also of importance for the subsequent history of the song is Mazzinghi's version: -wagon and new arrangements were for example published by Joseph Mazzinghi, John Parry, Antony Corri, Thomas Howell, William Ling and Charles Stokes (see more reviews in Repository of Arts, Literature, Vol. 7, 1812, p. 288; The Monthly Magazine, 1812, Vol. 33, pp. 53, 166; Vol. 34, pp. 155, 445) as well as Anne-Marie Krumpholtz (see Copac and the Internet Archive) and Sophia Dussek (see Copac, online at Hathi Trust). Of particular interest and also of importance for the subsequent history of the song is Mazzinghi's version:

- Robin Adair, A Simple Irish Ballad. Sung with unbounded applause by Mr. Braham, At the Lyceum Theatre, Arranged with an Accompaniment for the Harp or Piano-forte, Also may be had with Variations for Piano Forte, Harp & Flute, By J. Mazzinghi, Printed by Goulding & Co., London n. d. [1812] (online available at Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music, Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections; see the review in Monthly Magazine, Vol. 33, 1812, No. 224, March 1, p. 166)

Joseph Mazzinghi (1765-1844; see BDA 10, pp. 159-161; New Grove, 2nd ed., 16, pp. 192-3), an English composer of Corsican descent, was one of the mainstays of the music scene in London at that time and he apparently had always his finger at the pulse of popular taste. So it is no wonder that he also threw his hat in the ring. At first it is important to note that here this song was called an "Irish ballad". I assume Mr. Mazzinghi was perfectly familiar with the tune's history and he surely also saw it's connection to Thomas Moore's "Erin, The Tear And The Smile In Thine Eyes" that had been published three years earlier. Interestingly he simplified the melody line a little bit. The "Scotch Snap" was only retained for the last refrain line and he also corrected measure 10 where he the octave was replaced with the original interval. In fact his version looks much closer to Moore's variant of the tune than to Braham's. Not at least he - or the publisher - not only used the latter's new text but also included an alternate set of lyrics. The name of the author was not revealed. Instead there is only a note that it is the "property" of the publisher:

![19. Text and tune from: Robin Adair, A Simple Irish Ballad. Sung with unbounded applause by Mr. Braham, At the Lyceum Theatre, Arranged with an Accompaniment for the Harp or Piano-forte, Also may be had with Variations for Piano Forte, Harp & Flute, By J. Mazzinghi, Printed by Goulding & Co., London n. d. [1812] 19. Text and tune from: Robin Adair, A Simple Irish Ballad. Sung with unbounded applause by Mr. Braham, At the Lyceum Theatre, Arranged with an Accompaniment for the Harp or Piano-forte, Also may be had with Variations for Piano Forte, Harp & Flute, By J. Mazzinghi, Printed by Goulding & Co., London n. d. [1812]](../assets/images/autogen/RA-Mazzinghi-1812.png) |

Welcome on shore again,

Robin Adair!

Welcome once more again,

Robin Adair!

I feel thy trembling hand;

Tears in thy eyelids stand,

To greet thy native land,

Robin Adair!

Long I ne'er saw thee, love,

Robin Adair;

Still I prayed for thee, love,

Robin Adair;

When thou wert far at sea,

Many made love to me,

But still I thought on thee,

Robin Adair!

Come to my heart again,

Robin Adair;

Never to part again,

Robin Adair;

And if thou still art true,

I will be constant too,

And will wed none but you,

Robin Adair!

"Robin Adair" seems to have been ubiquitous during these years. Very quickly parodies appeared, for example one that was published in the Theatrical Inquisitor And Monthly Mirror in 1814 (p. 246, at Google Books) but apparently had been "written at the Time Mr. Braham first introduced it". I wonder if the "George" mentioned here is an allusion to the Prince of Wales:

What's all this noise about

Robin Adair?

Why this incessant rout

Robin Adair?

Tweedle dum - tweedle dee,

By George, I plainly see,

The world's a humming thee,

Robin Adair!

Thou art beloved, I'm told,

Robin Adair,

Because thou art so old

Robin Adair!

By some thou'rt finely dressed,

By others much caress'd,

With all a welcome guest,

Robin Adair.

What makes the play so fin?

Robin Adair.

What gives a zest to wine?

Robin Adair.

What, when my song is o'er,

Will make you loudly roar,

Encore! Encore! Encore?

Robin Adair.

The song was even referred to in Jane Austen's Emma (see chapter 28, p. 216 in this edition from 1896):

And of course more artists including some stars of the European music scene felt it necessary to add this piece to their repertoire. German piano virtuoso Friedrich Kalkbrenner - who lived in England since 1814 - wrote a Fantaisie for the Piano Forte in which is Introduced the Favorite Air of Robin Adair (available at NAIC; naa) and in the early 20s Italian singer Angelica Catalani sang a version of the song with variations composed for her by Sir John Stevenson that was also published as sheet music (available at NAIC, naa). In June 1826 a writer for the magazine Harmonicon noted that the song had been "sung, piped, fiddled, whistled, drummed and harmonized to death in this country to bear reviving just at present" (p. 119). But it was not laid to rest and instead remained popular in England throughout the 19th century. Braham's version was regularly published again, for example in songbooks from the 40s and 50s like Bingley's Select Vocalist (1842, p. 124) or Davidson's Universal Melodist (1847, p. 286, here without the "Scotch Snap"). The text also appeared on numerous broadsides (see for example Harding B 17(258b) and Harding B28(56) at Broadside Ballads Online), there were new arrangements (see Copac) and the tune was used for new songs including parodies like "Moggy Adair" (see for example Harding B16(151b), at BBO).

The song also quickly migrated to North America. Braham's original version was reprinted by publishers like Dubois in New York (available at the Levy Collection). In 1817/18 young English singer Henry Phillips (1801-1876, see The New Grove, 2nd ed., 19, pp. 598-9) sang "Robin Adair" on his very successful tour. One critic noted that "Mr. Philipp's performances excite universal applause wherever he is seen" (New York Evening Post, 11.3.1818, AHN) and Poulsen's American Daily Advertiser on December 17th, 1817 (AHN) remarked that the song "will long vibrate in our ears, when the singer and actor has taken his leave". That was correct and it seems that it became even more popular in the USA than in Britain. The text and the tune were included numerous publications of all kinds like songsters, magazines or music books.

"Robin Adair" looks like an early example for what today would be called an international hit and it became also known in France. Of course Kalkbrenner's Fantaisie was published in Paris (see the sheet music at IMSLP). But most important in this respect was its inclusion in an immensely popular French opera: La Dame Blanche by Francois-Adrien Boieldieu (1775-1834) with a libretto by Eugéne Scribe (1791-1861). Boieldieu was one of the most successful French opera composers of that era. He wrote more than 40 pieces for the stage and many of them were performed all over Europe. The debut performance of this opéra comique was on December 10th, 1825 in Paris. It became an instant success and remained a part of the standard repertoire for the stage for nearly a century.

This opera is set in Scotland and the plot is loosely based on some works by Sir Walter Scott, especially Guy Mannering and The Monastery. For that reason Boieldieu used some Scottish tunes, besides "Robin Adair" for example also "The Yellow Hair'd Laddie". The story looks a little bit simplistic (see this textbook in French and English, available at the Internet Archive). The hero is a young officer by the name of Georges Brown who arrives in a village called Avenel. The local castle has just been set up for sale by auction. But with the help of the "White Lady", in fact a girl who once had treated his wounds after a battle, he is able to buy the castle and pay the price with the money from the former owners' secret treasure. In the end he turns out to be the real heir of the house of Avenel. The bad guy has to leave and Georges can marry the girl. The tune of "Robin Adair" appears in the 3rd scene of the 3rd act and is simply called an "air écossais" (see textbook, pp. 35-6 and piano version, pp. 322-326):

At this point Georges had already purchased the castle by auction but hadn't yet paid the price because he didn't have any money. But he is welcomed and celebrated by the people of the village and young girls bring him the keys of the castle. Then the choir starts singing "le chant ordinaire de la tribu d'Avenel":

Chantez la guerre,

Beau ménestrel,

Chantez la guerre,

Beau ménestrel

Luckily he remembers the tune:

Attendez, attendez, attendez,

J'achéverais, je crois

And then he hums the second part. Everybody is happy that Georges still knows "des vieux airs de notre patrie" and they all celebrate "notre noveau seigneur". The tune serves here as a means to identify the long lost heir. The idea is good but why exactly the composer used "Robin Adair", first a drinking song and then a popular tearjerker, is not that easy to understand. Boieldieu's source was clearly Braham's version and he has retained the "Scotch snaps" in the refrain lines:

But the second part looks a little bit different. He has conflated measures 9 and 10 as well as 13 and 14 to a four bar-phrase. Measures 11 and 12 were dropped and instead these four bars are repeated. The tune's second part now has 10 instead of 8 bars and this would later create some problems for arrangers who wanted to combine this variant form of the melody with lyrics written to the original version of the song. Boieldieu's "air écossais" from La Dame Blanche was the start of a new line of tradition that will become especially important for the history of the tune in Germany. This will be discussed in the following chapters.

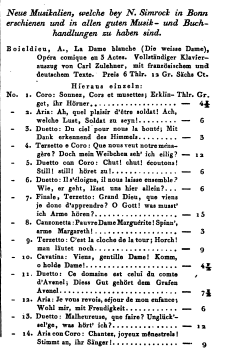

II. How "Robin Adair" Came To Germany

The story of "Robin Adair" in Germany started with Boieldieu's La Dame Blanche. One can not say that the tun e was completely unknown there. For example Kalkbrenner's Fantaisie sur Robin Adair was of course also offered by German music sellers (see Whistling 1817, p. 361, at BStB-DS). Hofmeister in Leipzig published Mauro Giuliani's Six Airs Irlandois nationales. Varieés pour la Guitarre that included "Robin Adair" as No. 4 (see sheet music: Boijes Samling 244, at Statens Musikverk, Stockholm). But I have found no evidence that song was more widely known in Germany at that time. By all accounts Braham's version was never sold there before 1826 and it seems there was no mention of it in the music press. But Boieldieu's opera took the German music lovers by storm and popularized the tune. Already in April 1826 a piano version of La Dame Blanche including a German translation was published. All the arias were also available individually (see the ad in AMZ 28, No. 17, 1826, Intelligenzblatt VIII, p. 36, at BStB-DS): e was completely unknown there. For example Kalkbrenner's Fantaisie sur Robin Adair was of course also offered by German music sellers (see Whistling 1817, p. 361, at BStB-DS). Hofmeister in Leipzig published Mauro Giuliani's Six Airs Irlandois nationales. Varieés pour la Guitarre that included "Robin Adair" as No. 4 (see sheet music: Boijes Samling 244, at Statens Musikverk, Stockholm). But I have found no evidence that song was more widely known in Germany at that time. By all accounts Braham's version was never sold there before 1826 and it seems there was no mention of it in the music press. But Boieldieu's opera took the German music lovers by storm and popularized the tune. Already in April 1826 a piano version of La Dame Blanche including a German translation was published. All the arias were also available individually (see the ad in AMZ 28, No. 17, 1826, Intelligenzblatt VIII, p. 36, at BStB-DS):

- La dame blanche. Opera comique en trois Actes. Die weisse Dame. Vollständiger Clavierauszug von C. Zulehner. Mit französischem und deutschem Texte. Die deutsche Uebersetzung ist von Fr. Ellmenreich, Simrock, Bonn c. 1826 (available at the Internet Archive; see the review in Caecilia Mainz, Vol. 5, 1826, p. 81, at Google Books)

The relevant lines of the "Air écossais" (see pp. 170/1) were of course not too difficult a challenge for Mrs. Ellmenreich, a former singer and actress who regularly translated the librettos of foreign operas:

Laut tön' das Siegeslied,

ja, laut und hell.

Laut tön' das Siegeslied,

ja, laut und hell.

La, la, la, la la [etc]

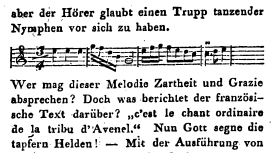

The debut performance of the German version - with the title Die Dame auf Avenel - was in Vienna o n July, 6th and on August 1st opera fans in Berlin first saw this piece (see AMZ, 28, No. 37, September 1826, pp. 603, 608, at BStB-DS). A reviewer in the Berliner Allgemeinen Musikalischen Zeitung (Vol. 3, Nr. 32, August 1926, pp. 255-7, at BStB-DS) was not always impressed by neither Boieldieu's and Scribe's work nor this piano version. Especially the way the composer had used the Scottish air didn't seem too convincing to him (p. 257): n July, 6th and on August 1st opera fans in Berlin first saw this piece (see AMZ, 28, No. 37, September 1826, pp. 603, 608, at BStB-DS). A reviewer in the Berliner Allgemeinen Musikalischen Zeitung (Vol. 3, Nr. 32, August 1926, pp. 255-7, at BStB-DS) was not always impressed by neither Boieldieu's and Scribe's work nor this piano version. Especially the way the composer had used the Scottish air didn't seem too convincing to him (p. 257):

"In the third act, everything clears up, only in the music prevails a dismal gray. The choir sings the song of the House of Avenel, but the listener believes to see a troop of dancing nymphs in front of him. Who could deny this tune's delicacy and grace? But what says the French text? 'c'est le chant ordinaire de la tribu d'Avenel.' God bless the brave heroes!"

He also reported a "lukewarm reception" of some of the arias. But already at that time the critics and the audiences in Berlin were sometimes living on another planet and by all accounts this opera became very successful in Germany. Two months later another reviewer noted that Boieldieu's "admirable music has won a lot of friends" (AMZ 28, No. 42, October 1826, p. 684). Soon afterwards the opera was staged five times in Leipzig (see AMZ 28, No. 52, December 1826, p. 855) and performances in towns like Kassel, Stuttgart, Bremen and Dresden followed (see AMZ 29, 1827, pp. 140, 182, 588, 811, at BStB-DS). In Vienna even a parody with the title Die Schwarze Frau ("The Black Lady") was produced (see AMZ, 29, No. 6, Februar 1827, p. 98).

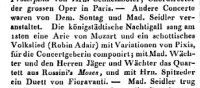

Of course every publisher jumped on this new bandwagon and threw the opera's music in piecemeal fashion - for every possible instrument - on the market. The copyright law was clearly not such a big problem at that time. In fact the sheer number of relevant publications that were made available in the following two years is somehow staggering (see for example Intelligenzblatt zur Caecilia, 1826, No. 18, pp. 22-25, at Google Books, Whis![23. From: Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur, oder allgemeines systematisches Verzeichnis gedruckter Musikalien, auch musikalischer Schriften [...], Zehnter Nachtrag, C. F. Whistling, Leipzig 1827, p. 56 23. From: Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur, oder allgemeines systematisches Verzeichnis gedruckter Musikalien, auch musikalischer Schriften [...], Zehnter Nachtrag, C. F. Whistling, Leipzig 1827, p. 56](../assets/images/autogen/LDB-Whistling1827-p56-b.png) tling 1827, pp. 4, 6, 10, 23, 29, at BStB-DS). The vocal pieces were also brought out as sheet music. Whistling's Handbuch (1827, p. 56, at BStB-DS) reported the publication of "individual arias" by Schott, Lischke, Cranz, Böhme, Haslinger and one more version was printed in 1828 by Diabelli in Vienna (see BStB, catalog). Not at least there were also arrangements for the guitar, both instrumental and vocal, like the Gesänge aus der weißen Dame in two volumes by Breitkopf & Härtel and Favorit-Gesänge mit Begleitung der Guitare aus der Oper Die weisse Frau, again by Diabelli (see Whistling 1827, p. 64). It seems that this music was easily available for anyone who wanted to play it at home and especially the "Scottish air" must have familiar to many amateur musicians and their listeners. tling 1827, pp. 4, 6, 10, 23, 29, at BStB-DS). The vocal pieces were also brought out as sheet music. Whistling's Handbuch (1827, p. 56, at BStB-DS) reported the publication of "individual arias" by Schott, Lischke, Cranz, Böhme, Haslinger and one more version was printed in 1828 by Diabelli in Vienna (see BStB, catalog). Not at least there were also arrangements for the guitar, both instrumental and vocal, like the Gesänge aus der weißen Dame in two volumes by Breitkopf & Härtel and Favorit-Gesänge mit Begleitung der Guitare aus der Oper Die weisse Frau, again by Diabelli (see Whistling 1827, p. 64). It seems that this music was easily available for anyone who wanted to play it at home and especially the "Scottish air" must have familiar to many amateur musicians and their listeners.

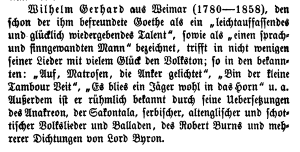

The first German text for this tune was written by poet Wilhelm Gerhard after he had seen a performance of La Dame Blanche. It was published on November 15th, 1826 in a popular newspaper, the Abend-Zeitung from Dresden and Leipzig (No. 273, pp. 1089-90, BStB-DS) together with a short article about this song. Gerhard (1780-1858) is more or less forgotten today but his life and career were in fact very interesting and noteworthy (see as a short summary Goedeke, Grundriß, pp. 894-5; an attempt at a biography: Jahović 1972). He was born in humble circumstances - his father was a small merchant - but became a very wealthy businessman in Leipzig who made a lot of money by importing and selling the products of English manufactures. Besides that he also led some kind of second life as a poet, writer and polymath and was interested in many fields of arts and sciences including geology and botanics. He even was personally acquainted with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who occasionally said some kind words about him and the great poet clearly served as something like a role model for him. One gets the impression that Gerhard tried to be a new Goethe. This is something that he of course never achieved but his life's work is nonetheless very impressive. In 1833 he was rich enough to close down his business and for the rest of his life devoted himself solely to the arts and his famous "garden", in fact a spacious park.

Two volumes of his poetry were already available in 1826 (Vol. 2 at Google Books). Some of this texts were set to music and became popular songs that would later appear in collections of so-called Volkslieder, for example "A, B, C, D, Wenn Ich Dich Seh'" or the "Matrosenlied". In the  course of his life he learned half a dozen languages and translated poetry from most of them. His adaptations of Serbo-Croatian songs found particular interest among his contemporaries. Later he also published a book of translations - or better adaptations - of Robert Burns' songs with a well-informed introduction (Robert Burns' Gedichte, deutsch von W. Gerhard, Leipzig 1840, av. at Google Books). Another collection of Scottish songs was titled Minstrelklänge aus Schottland, rhythmisch verdeutscht (Leipzig 1853, available at Google Books). course of his life he learned half a dozen languages and translated poetry from most of them. His adaptations of Serbo-Croatian songs found particular interest among his contemporaries. Later he also published a book of translations - or better adaptations - of Robert Burns' songs with a well-informed introduction (Robert Burns' Gedichte, deutsch von W. Gerhard, Leipzig 1840, av. at Google Books). Another collection of Scottish songs was titled Minstrelklänge aus Schottland, rhythmisch verdeutscht (Leipzig 1853, available at Google Books).

In 1826 Gerhard was amongst those who very much liked Boieldieu's opera. One may assume that he saw one of the performances in Leipzig. He particularly enjoyed the "Air écossais" in the third act but the tune sounded somehow familiar to him: "It seemed as if I had already heard the simple, heart-warming sounds of this song somewhere". He then recalled his trip to England some years ago, in 1818. In London at Vauxhall he had seen a popular British tenor singing this piece. Gerhard even found the tune and two texts among the music booklets he had brought back home from this journey.

Interestingly he used as the template for his German version not Braham's lyrics but those published with Mazzinghi's sheet music. The English text was subtitled "A most admired Irish Ballad". This is in fact a mixture of the subtitles from both sheet music editions. On Braham's the song had been called "a much admired Ballad" and on Mazzinghi's "a simple Irish Ballad". Apparently Gerhard had acquired copies of both prints. His new German text was then presented as an "Irländisches Volkslied":

Treu und herzinniglich,

Robin Adair,

Tausendmal grüss´ ich dich,

Robin Adair!

Hab´ ich doch manche Nacht

Schlummerlos hingebracht,

Immer an dich gedacht,

Robin Adair!

Dort an dem Klippenhang,

Robin Adair,

Rief ich oft still und bang:

Robin Adair!

Fort von dem wilden Meer!

Falsch ist es, liebeleer,

Macht nur das Herze schwer,

Robin Adair!

Mancher wohl warb um mich,

Robin Adair!

Treu aber liebt' ich dich,

Robin Adair!

Mögen sie andre frei'n!

Will ja nur dir allein

Leben und Liebe weih'n,

Robin Adair!

This is in fact not an exact translation but a rather free adaptation. He was later criticized for that approach (see Grünhagen im Grenzboten 1906, pp. 670-2, av. at SUB Bremen) but in his article he humbly admitted that his text should only be regarded as "a weak attempt to make this ditty ["das Liedchen"] understandable to German ears and singable for German voices". Gerhard even discussed the difficulties of translating English lyrics to German and noted that he had tried to capture the spirit of the song instead of simply translating the words and otherwise "let his imagination run free". He even invited other interested poets to try their hand at this piece and a week later the Abend-Zeitung (No. 279, 22.11.1826, p. 1114, at BStB-DS, p. 1114) published a text by one Fr. Laun that was much closer to the original words.

Gerhard's new lyrics were in fact more than simply an "attempt". It is clearly the work of a skilled poet who knew what he wanted to achieve. At the time of writing they already sounded somewhat old-fashioned and today even more so. The word "herzinniglich" - it means something like "wholeheartedly" - is especially noteworthy. Even back then this expression was not that common but nowadays it sounds very out-dated. But it apparently served as a kind of textual hook that increased the song's recognition value.

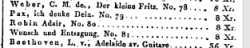

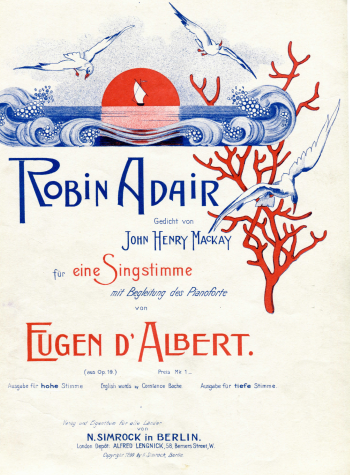

In his article he also noted that the other English text was prepared for publication with music by Hofmeister in Leipzig. In fact it came out the following year. In Whistling's Handbuch der musikalische Literatur for the yea![25. From: Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur, oder allgemeines systematisches Verzeichnis gedruckter Musikalien, auch musikalischer Schriften [...], Zehnter Nachtrag, C. F. Whistling, Leipzig 1827, p. 62 25. From: Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur, oder allgemeines systematisches Verzeichnis gedruckter Musikalien, auch musikalischer Schriften [...], Zehnter Nachtrag, C. F. Whistling, Leipzig 1827, p. 62](../assets/images/autogen/RA-ad-Hm-Whistling1827-p62.png) r 1827 this edition is listed as "Irländisches Volkslied mit engl. u. deutschem Text von Gerhard" (p. 62, at BStB-DS) and it was sold for "4 Gr.": r 1827 this edition is listed as "Irländisches Volkslied mit engl. u. deutschem Text von Gerhard" (p. 62, at BStB-DS) and it was sold for "4 Gr.":

- Robin Adair a Simple Irish Ballad - Robin Adair, Jrländisches Volkslied von Wilhelm Gerhard für Harfe oder Pianoforte, Hofmeister, Leipzig, n. d. [1827] (only extant copy at the Library of the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn, Geyr 42 u)

As can be seen the song was called here a "simple Irish ballad" á la Mazzinghi. Gerhard's German text was also included but set to Braham's version of the tune together with the latter's original words:

Buyers of this publication with a knowledge of the English language may have wondered what these two texts had to do with each other. Apparently Gerhard had brought home a copy of Button & Whittaker's original sheet music that he then forwarded to Hofmeister. Not only Braham's vocal line is copied note for note but also the piano arrangement looks in places suspiciously similar to what the late Mr. Reeve had written for the English edition. But on Hofmeister's sheet music there is no reference to Braham, Reeve or Button & Whittaker and this new publication comes close to a model example for international music piracy by a respected publishing house. Of course these kind of methods were not uncommon at that time.

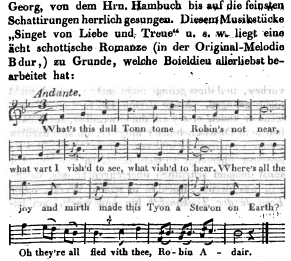

Interestingly at about the same time Mazzinghi's variant of the tune was made available in Germany, but not as sheet music. We  can find it in a review of a performance of La dame Blanche in Stuttgart that was published in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (Vol. 29, No. 11, March 1827, p. 183). The writer called the song "eine ächt schottische Romanze" [a true Scottish romance] but strangely Mr. Mazzinghi's variant was combined here with a very mutilated can find it in a review of a performance of La dame Blanche in Stuttgart that was published in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (Vol. 29, No. 11, March 1827, p. 183). The writer called the song "eine ächt schottische Romanze" [a true Scottish romance] but strangely Mr. Mazzinghi's variant was combined here with a very mutilated version of Braham's text. Another edition of this song was published by Schott in Mainz in 1828. They announced it as "Robin Adair, No. 80" in a series called Gesänge mit Piano- oder Harfe- oder Guitarre-Begleitung (Intelligenzblatt zur AMZ, Vol. 30, No. XXI, Dezember 1828, p. 84, at Google Books): version of Braham's text. Another edition of this song was published by Schott in Mainz in 1828. They announced it as "Robin Adair, No. 80" in a series called Gesänge mit Piano- oder Harfe- oder Guitarre-Begleitung (Intelligenzblatt zur AMZ, Vol. 30, No. XXI, Dezember 1828, p. 84, at Google Books):

- No. 80, Robin Adair a simple Irish Ballad. Robin Adair Jrländisches Volkslied für Harfe oder Pianoforte oder Guitarre, Mainz bey B. Schott's Söhnen, n. d. [1828] (online available at the library of the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp (Artesis University College of Antwerp), Historical Collection)

As he title suggests this was simply a reissue of Hofmeister's version, but without any reference to the original edition. The tune, the texts and the piano arrangement are exactly the same. Only a guitar part was added and for some reason the publisher left out Wilhelm Gerhard's name.

One more version of "Robin Adair", also with both Braham's and Gerhard's lyrics, can be found on an undated sheet music published by Cranz in Hamburg:

- Robin Adair Schottische Ballade. Benutzt in der Oper Die weisse Frau von A. Boieldieu. Für Pianoforte oder Guitarre, No. 12, Pr. 4 Gr., Hamburg bei A. Cranz, [n. d.] (only extant copy at Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Musiksammlung, MS12858-qu.4)

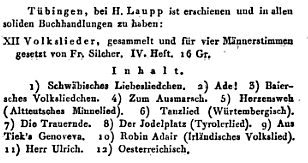

I assume this was one of the "individual arias" by Cranz that were mentioned in Whistling's Handbuch in 1827 (p. 56, at BStB-DS). In fact it is not Braham's version of the tune. Here the two texts were combined - as the title says - with the variant from La Dame Blanche. Therefore the song was designated not as "Irish" but as "Scottish" and only as "Ballade" but not as a "Volkslied". It is also notable that again Gerhard was not credited as the originator of the German words although it couldn't have been too difficult to find out. I assume this was a deliberate omission:

![29. Text (first verse only) and tune from sheet music: Robin Adair Schottische Ballade. Benutzt in der Oper Die weisse Frau von A. Boieldieu. Für Pianoforte oder Guitarre, No. 12, Pr. 4 Gr., Hamburg bei A. Cranz, [n. d.] 29. Text (first verse only) and tune from sheet music: Robin Adair Schottische Ballade. Benutzt in der Oper Die weisse Frau von A. Boieldieu. Für Pianoforte oder Guitarre, No. 12, Pr. 4 Gr., Hamburg bei A. Cranz, [n. d.]](../assets/images/autogen/RA-Cranz-1827.png) |

As can be seen here there were certain difficulties with using Braham's and Gerhard's texts with Boieldieu's variant of the tune. That one consists of 18 bars - the B-part is two bars longer - while the former were conceived for a melody of 16 bars. The solution to this problem applied here was is not particularly convincing. The refrain line already starts in measure 15 and that doesn't sound right. It is then even repeated three times. The very same version was also included in another publication, but there only with Gerhard's German words and an arrangement for guitar that is not that dissimilar to the one used in Cranzen's sheet music:

- Arion. Sammlung auserlesener Gesangstücke mit Begleitung der Guitarre, 1. Band, Braunschweig, bei F. Busse, n. d. [1828/9], No. 47, p. 82 (available online: Boijes Samling 899, Musik- och Teaterbiblioteket, Statens musikverk, Stockholm)

In 1828 publisher Heinrich Busse from Braunschweig started a couple of interesting series of songbooks with somewhat bombastic titles like Arion. Sammlung auserlesener Gesangstücke mit Begleitung des Pianoforte resp. Guitarre, Orpheus. Sammlung auserlesener mehrstimmiger Gesänge ohne Begleitung and Amphion. Sammlung auserlesener Tänze für das Pianoforte. These were cheap and handy volumes and they were at first sold as booklets with each including 7 or 8 songs but priced only at 4 Gr. This was in fact a very good offer. The major publishing houses like Hofmeister, Cranz or Schott used to sell a single song for the same price.

Six consecutive booklets were later bound to one book. The first volume of Arion included songs and arias for example by Weber, Pollini, Spohr und Kreutzer. These were more or less the most popular songs of that time. In the preface to the first volume of this collection Busse claims that because of a new printing technique these books were "so remarkably cheap that even the less well-off can afford it". But to be true his business model was very obviously the reprint of pieces originally published by the big music firms. The composers of the borrowed songs were of course named but Mr. Busse strictly refrained from acknowledging his sources or even the arrangers.

His rivals were not amused, in fact they were very annoyed and called for a boycott of Busse's publications (see for example Intelligenzblatt zur Allgemeinen Musikalischen Zeitung, Vol. 30, No. IX, June 1828, p. 33, at BStB-DS, also Die Freie Presse, No. 35, 27. 8. 1829, p. 144, at Google Books, for the background see Kawohl 2008 at copyrighthistory.org). Among the publishers involved in this campaign were Hofmeister, Peters, Schott, Simrock as well as Breitkopf & Härtel, but for some reason not Cranz. They bemoaned the lack of legal protection for music and announced that they had to take care of their rights themselves.

Of course their allegations were correct. But it all sounds like the pot calling the kettle black because they also indulged in this kind of musical piracy. As noted above Hofmeister had copied text, vocal line and at least a part of the piano arrangement from the original English sheet music of "Robin Adair" for their own edition without acknowledging the source. This was common practice at that time. For example I seriously doubt that any of the income generated from the numerous editions of the music of La Dame Blanche reached the composer in Paris. By all accounts this boycott wasn't particularly successful and Busse's series apparently became very popular. A music seller in Frankfurt announced these collection in June 1830 in local Intelligenzblatt (Dritte Beilage zu Nro. 49, n. p.) with some appropriate words:

"Angenehme Auswahl bei einer sorgfältigen Austattung und überaus billigen Preisen haben diesen Musiksammlungen überall willkommenen Eingang verschafft, und es ist daher zu erwarten, dass sie auch hier eine freundschaftliche Aufnahme finden werden"

About 10 volumes of Arion appeared during the following years and they were later also reprinted by another publisher in Leipzig. One can find them easily in library catalogs, even in Britain (see Copac) and I have seen some of them also in sales lists of old book shops. So it seems there were quite popular at that time.

"Robin Adair" can be found in booklet No. 6 of the first volume that appeared early in 1829, but for some reason not in the edition for pianoforte but only in the one for guitar (No. 47, p. 82). This version was clearly "borrowed" from Cranzen's sheet music who seems to have been the first publisher to combine Gerhard's text with Boieldieu's tune variant:

We can see that at the end of the 1820s already two German versions of "Robin Adair" were available. In both cases Wilhelm Gerhard's "Treu Und Herzinniglich" served as the text. For Hofmeister's sheet music these words were set to Braham's original tune and this variant was designated - thanks to Mazzinghi - as "Irländisches Volkslied". Cranz instead resorted to the tune from La Dame Blanche and called it "Schottische Ballade". Both were the starting-point for a particular line of tradition and all later published versions of the song can be traced back to one of them.

Besides these music prints Gerhard's text was also published on what looks like a chapbook from around 1830:

- Vier neue Lieder. 1. Der Aschenmann und ein Mädchen. 2. Als ich ein schönes Mädchen sah. 3. Treu und herzinniglich, Robin Adair. 4. Arie aus der Schweizer Familie [Herz mein Herz, warum das Kränken], n. p., n. d. [before 1832] (only extant copy at Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Weimar, Dd3:63[3][a]; I wish to thank the library for sending me a digital copy of this print)

This is an interesting collection of popular songs old and new. The first piece here is from Ferdinand Raimund's popular play Das Mädchen aus der Feenwelt oder Der Bauer als Millionär (1826) while the fourth was lifted from Joseph Weigl's opera Die Schweizer Familie (1809). According to Otto Holzapfel's Liedverzeichnis (2006, Vol. 2, p. 1298) Gerhard's text was also included in other undated so-called Liedflugschriften. One date listed there, "Hamburg, um 1815-20", is much too early because the song was of course only available since 1826. The other two may have been published much later. On one of them the title was mutilated to "Treu und herzinniglich, Ruminatör".

Of course "Robin Adair" was also performed in Germany by popular artists of that era. Henriette Sontag, one o f the great international stars at that time (see Wikipedia), sang this piece for example in Berlin in March 1827 (see AMZ 29, No. 18, 2.5.1827, p. 309, at BStB-DS). Composer Johann Peter Pixis had written variations for her. Perhaps she wanted to outdo her great rival Angelica Catalani whose own variations for this song had been - as noted above - composed by Sir John Stevenson. Her version was also published as sheet music in England: f the great international stars at that time (see Wikipedia), sang this piece for example in Berlin in March 1827 (see AMZ 29, No. 18, 2.5.1827, p. 309, at BStB-DS). Composer Johann Peter Pixis had written variations for her. Perhaps she wanted to outdo her great rival Angelica Catalani whose own variations for this song had been - as noted above - composed by Sir John Stevenson. Her version was also published as sheet music in England:

- Robin Adair: with Variations for the Voice, as sung by Madlle Sontag, at the Public & Private Concerts, Composed expressly for her & Arranged with an Accompaniment for the Piano Forte, by I. P. Pixis (available at BStB & Google Books; see also the rather negative review in Harmonicon, Vol. 4, No. XLVI, October 1826, pp. 197-8, at Google Books)

This publication included English, Italian and German lyrics, the latter a new translation. Pixis also wrote variations for the piano that were published in Paris but of course were also available in Germany (see Whistling 1828, p. 758, at Google Books)

III. Herder's Cuckoo's Egg - Some Notes About The Term "Volkslied"

At this point it is necessary to return to Wilhelm Gerhard and the very first publication of his adaptation in 1826. The German text is entitled: "Robin Adair. Irländisches Volkslied". The reference to Ireland was of course borrowed from Mazzinghi's sheet music but the use of the term "Volkslied" appears at first glance a little bit surprising. On the original English sheet music the song had only been called a "A simple Irish ballad" (Mazzinghi) or "The much admired ballad" (Braham). On other contemporaneous editions of "Robin Adair" we find descriptions like "popular ballad", "favourite Air" or "celebrated ballad". The German term "Volkslied" must be discussed here in greater detail because this designation was retained for many later editions of the song, not only those derived from Hofmeister's original sheet music. Later it was also applied to the versions using Boieldieu's tune variant which had at first only been labeled as "Schottische Ballade".