|

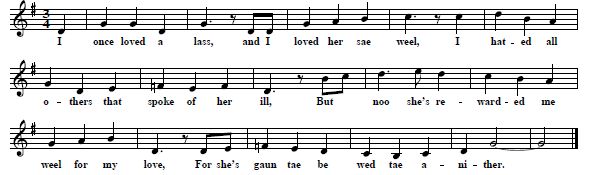

"I Once Loved A Lass..." -

The Story Of The "False Bride"

And Her Forsaken Lover

I.

This is an attempt at unraveling the history of a very old and very interesting song family. The earliest texts are from the 1670s, for example a broadside ballad called "The Forlorn Lover" (Douce Ballads 1(83a) at BBO, Bodleian Library). But versions of this song are still performed today, 340 years later. A Scottish variant called "I Loved A Lass" was recorded first by Ewan MacColl with Peggy Seeger in 1956 for the LP Classic Scots Ballads (TLP 1015, song available on YouTube). At the moment many cover versions are available (see at amazon.com: "I Loved A Lass" and "I Once Loved A Lass").

|

|

|

|

- I once loved a lass, and I loved her sae weel

I hated all others that spoke of her ill;

But noo she's rewarded me weel for my love,

For she's gaun to be wed till anither.

When I saw my love to the church go,

Wi' bride and bride-maidens, they made a fine show;

An' l followed them on wi' a heart fu' o' woe,

For she's gaun to be wed till anither.

When I saw my love sit down to dine,

I sat down beside her and poured out the wine,

An' I drank to the lass that should ha'e been mine,

An' now she is wed till anither.

The men o' yon forest they askit o' me,

Hou many strawberries grew in the saut sea?

But I askit them back wi' a tear in my ee',

How many ships sail in the forest?

O dig me a grave and dig it sae deep,

An' cover it over with flow'rets säe sweet,

An' I'll turn in for to tak' a lang sleep,

An' may be in time I'll forget her.

They dug him a grave an' they dug it sae deep,

An' covered it over with flow'rets säe sweet,

An' he's turned in for to tak' a lang sleep,

An' maybe by this time he's forgot her.

|

|

|

An English variant with the title "The False Bride" was published in 1959 in The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs (1959) and then recorded in 1960 by A. L. Lloyd for the LP A Selection From The Penguin Book Of English Folk Songs (Collector JGB 5001, see Mainly Norfolk; see that site also for the lyrics of other versions). From Ireland we have Sarah Makem's "I Courted A Wee Girl" (on Ulster Ballad Singer, Topic 12T 182, 1968; song available at YouTube, lyrics at traditionalmusic.co.uk). The song was also known under titles like "The Week Before Easter", "The False Hearted Lover", "The Forsaken Bridegroom" or "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" or "The False Nymph".

Here I will use Ewan MacColl's "I Loved A Lass" as the focal point because it seems to be the standard version today. At first I will delineate the history of the commercially published variants of this song. Five different texts were published on broadsides between the 1670s and the end of the 19th century. Then I will discuss some selected variants collected from oral tradition. It is important to distinguish between these two worlds although they are of course closely intertwined. The broadsides were aimed at customers interested in "new" songs while the Folk song collectors were looking for "old" songs.

II.

The first two published versions of songs from this family can be found on broadsides from the 17th century. One was a ballad of 16 verses printed in London "for F. Coles, T. Vere, and J. Wright" between 1663 and 1674:

- The Forlorn Lover, Declaring How A Lass gave her Lover three slipps for a Teaster, And married another a Week before Easter, To a pleasant new tune (Douce Ballads 1(83a) at BBO, Bodleian Library, also Wing 2nd ed. F1559B at EEBO)

|

|

|

|

A Week before Easter, the days long and clear,

So bright is the Sun and so cold is the ayr;

I went into the Forrest, some flowers to find there,

And the Forrest would yield me no Posies.

The Wheat and the Rye that groweth so green,

The Hedges and Trees in their several Coats,

Small Birds do singin their changeable notes,

But there grows no Strawberries or Roses.

I went in the Meadow some time for to spend,

And to come back again, did fully intend:

But as I came back I met with a friend,

And love was the cause of my mourning.

I lov'd a fair Lady this many a long day,

And now to requite me, she married away;

Here she hath left me in sorrow to stay,

But now I begin to consider.

I Loved her dear, and I loved her well,

I hated those people that spoke of her ill;

Many a one told me what she did say,

But yet I would hardly believe them.

But when I did hear my love askt in the Church,

I went out of my seat,and sat in the porch:

I found I should falsly be left in the lurch,

And thought that my heart would have broken.

But when I did see my Love to the Church go,

With all her Bride-Maidens they made such a show;

I laught in conceit, but my heart was full low,

To see how highly she was regarded.

But when I saw my lovein the Church stand,

Gold Ring on her Finger, well seal'd with a hand:

He had so seduc'd her with house and with Land,

That nothing but Death can them sever.

|

But when the Bride-Maidens were having her to Bed,

I stept in amongst them and kissed the Bride:

I wisht I might have been laid by her side,

And by that means I got me a favor.

When she was laid in bed, (drest up in white)

My eyes gusht with water, that drowned my sight:

I put off my Hat,and bid them good-night,

And adieu my fair sweeting for ever.

Oh dig me a Grave that is wide, large, and deep,

With a root at my head, and another at my feet:

There will I lye and take a long sleep,

I'le bid her farewel for ever.

She plighted her faith,to be my fair Bride,

And now at last hath me falsly depriv'd;

I'le leave off my wrath, and with God be my guide,

To save me from such another.

I pitty her case, much more then my own,

That she should imbrace and joyn hands in one:

Whilst I am her true love,and daily do groan,

My sorrow I cannot smother.

Though Marriage hath bound her,she is much to blame,

And though he hath found her, her Husband I am;

Hereafter 'twill wound her,that she put them to shame,

When Conscience shall be her accuser.

Two Husbands she hath by this wild miscarriage,

The one by a Contract, the other by Marriage:

She doth her whole Family grossly disparage,

But I will not plot to misuse her.

Beware you young-men, of Arts or of Trades,

Chuse warily when you meet with such Maids:

You'd better live singlealone in the Shades,

Then to love such an abuser.

|

|

|

|

"Three slips for a tester" - "three counterfeit twopenny coins for a sixpence" - was a proverbial expression meaning "to elude" (Rollins 1922, p. 270, at the Internet Archive). There had already been a broadside with that title:

- A Quip For A Scornful Lasse, Or, Three Slips For A Tester, To The Tune Of Two Slips For A Tester, London 1627 (Pepys 1.234-235 at EBBA)

The song has an interesting rhyme scheme: aaab. The first three lines of a verse should rhyme with each other. This is not always the case. In the second stanza the first line does not rhyme and the fifth verse isn’t perfect either. There also some attempts at a secondary rhyme scheme. The final lines of verses 1 and 2 (posies, roses) rhyme with each other as do those of verses 8, 9, 10, and 11 (sever, favour, ever, ever), 12 and 13 (another, smother) and also 14, 15, 16 (accuser, misuse her, abuser). William McCarthy in his book The Ballad Matrix sees the inconsistent rhyme scheme as a sign that the text "is an abbreviated and otherwise modified reprinting of an earlier and lengthier version in which stanzas were linked together by a pattern of rhymes in the final lines of each stanza" (p. 47). This isn’t entirely convincing.

The last five verses don't add anything to the story. They sound forced and for me it looks as if they were pasted on at the end of the song. It should also be noted that the secondary rhyme scheme works best in these stanzas. It seems to me more likely that the anonymous editor padded out an earlier shorter version by adding these verses and then also tried - not always successfully - to introduce rhymes into the final lines of the other verses. John Holloway in his introduction to the Euing Ballads (p. x) remarks that the "expansion of an earlier text" was a common technique among ballad writers.

The verse starting with "Oh dig me a grave [...]" was later used in other songs, a variant form can be found for example in "The Butcher Boy" (see Harding B 18(71), Philadelphia 1860, at BBO). This verse has also survived in McColl's "I Loved A Lass" although it looks a little bit different there and is repeated a second time in the third person ("They dug him a grave... [...]").

But there are some more parallels. Let's take the first half of the first line of the fourth verse in "The Forlorn Lover":

Then combine it with the second half of first line and the second line of the fifth verse:

This looks very similar to the first two lines of McColl's version:

I once loved a lass, and I loved her sae weel,

I hated all others that spoke of her ill

Also a variant form of the "Forlorn Lover's" seventh verse is used as the second verse of "I Loved A Lass":

- When I saw my love to the church go,

Wi' bride and bride-maidens, they made a fine show;

And I followed them on wi' a heart fu' o' woe,

For she's gaun to be wed till anither.

In fact two and a half verses from this old broadside text have survived until the 20th century.

The dating of this broadside that is now common in library catalogs is based on groundbreaking research by Cyprian Blagden (1954, pp. 163, 170-1) who showed convincingly that ballads with this particular imprint must have been published some time between 1663 and 1674. Francis Coles, John Wright and Thomas Vere were booksellers who at that time dominated the ballad market. In 1674 or 1675 John Clark[e] joined the partnership and on March 1, 1675 "The Forlorne Lover" and 174 other ballads (see Rollins, Analytical Index, No. 907, p. 83, also pp. 1 & 4) were entered into the Stationers' Register that "allowed publishers to document their right to produce a particular printed work, and constituted an early form of copyright law" (see Wikipedia).

Ballads had rarely been registered since 1656 and it seems that in 1675 Coles, Wright, Vere and Clarke simply submitted their back-catalog. Some of these 175 ballads had already been entered into the register earlier and the rest had been acquired in the intervening years. Blagden (p. 171) notes that some of these ballads "might have been first issued by partners, or of course by others without registration: many of the titles listed here for the first time must [...] have been originally the property of other booksellers.

The broadside was then reprinted between 1684 and 1686 for Clark, Thackerey and Passenger with the same woodcut but no other changes except a printer's error in the title (it now says "tester" instead of "teaster", Pepys 3.103 at EBBA) and then at the beginning of the nineties for "by W. O[nley]. and sold by the booksellers of Pye-corner and London-bridge" (see Copac, text reprinted in Roxburghe Ballads VI, p. 233-4).

There is also another version of this broadside available (Euing 1.112 at EBBA). It has the same text but different woodcuts. Unfortunately there is no imprint so it's not possible to find out the date of publication. The title still has "teaster" instead of "tester". McCarthy claims that this print is "from the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century" (p. 47). This seems highly unlikely to me and I am not aware of any evidence that would support this assumption. In the introduction to the Glasgow edition of the Euing Ballads Holloway states clearly that "by far the majority" of the pieces in this collection "are from the Restoration period, and a large number from the years 1685-88" (p. vii).Only very few of them were published earlier and there is no indication that the "Forlorn Lover" belongs to this small group.

Usually it's very difficult or even impossible to find out the exact date of when a ballad was first printed. In case of "The Forlorn Lover" it would be very interesting to know because there was a related ballad also published circa 1670:

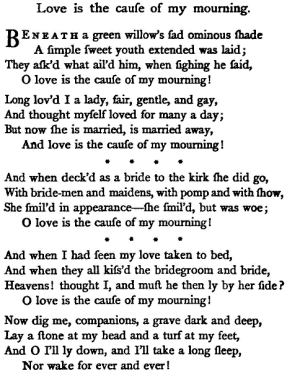

- Love is the Cause of my Mourning, Or, The Despairing Lover. Sung with its own proper tune, [ca 1670] (Wing L3211A, at EEBO)

This variant has only ten verses but tells the same story:

|

|

|

|

The week before Easter the day being fair,

The Sun shining bright, cold Frost in the Air,

I did me to the Orchard some flowers to pull there

But Flora could yield me no pleasures.

The hills being covered with Midsummers Clouds

The white and the red did spring from the Rocks,

The Birds they were tuning their musical Notes,

there was neither Cowslips nor Roses.

I had not been in this Wood half an hour spent,

When for to turn back again was my intent,

I heard a young Man who sore did Lament?

for Love was the cause of his mourning.

I loved a Lass this many a Day,

And for to requit me she is Marri'd away,

With sighing and Sobing Lamenting for ay,

which was the cause of his mourning.

Her Face was so fair I loved her well,

I hated all those that wished her evil,

They said of my Suit I would never prevail,

but yet I would never believe them.

|

.Her Face was so fair my Joy to behold,

Her Love I esteemed more dearer than gold;

For once she had my heart in her hold,

but yet with disdain she rewards me.

When that I did see my Love to the Kirk go,

With all her fair maids she had a fair show,

My Heart was so grieved I mourned for woe

to see me so lowly regarded.

When that I did hear the Clerk publickly cry,

Is there any contrary, its time to draw nye,

I thought in my mi[n]d good reason had I.

but yet it was best to conceal it.

When I did see my Love join Hand in Hand,

With Rings on her Finger to seal up that band,

Then I was insested[?] in goods, gear and land,

there was nothing but death could separat them.

When I did see my Love in her Bed right,

My Eyes gush'd out of water & blinded my sight,

I took off my Hat and bad her goodnight,

forsake her for she will not leave him.

|

|

|

|

It's not clear if this ballad was written and published before "The Forlorn Lover", it has no imprint and its origin is not known. Maybe it was an attempt to cash on in the success of the broadside published by Coles and his partners but it could have also been the original version of this song.

The rhyme scheme is the same as in "The Forlorn Lover" and this time only the first line of the second verse has the wrong ending. There are no attempts at a secondary rhyme scheme in the verses' final lines. But in two of them the phrase "[...] cause of his mourning" is used. Maybe there was an earlier unprinted version that had this line as a refrain in every verse just like the fragment published more than a hundred years later by David Herd in his Ancient And Modern Scottish Songs (1776, Vol. 2, p. 5). The last verse of this variant looks like a later addition.

Eight verses with some variations (1 - 5, 7, 9, 10) can also be found in "The Forlorn Lover" (1 - 5, 7, 8, 10). two are different (6, 8). Interestingly in this version also the verse where the narrator asks to dig him a grave is missing. Instead he "bid[s] her good night" and - if I understand it correctly - wants her to die from pox:

- Pox take her for she will not leave him [sic!].

This text was published again in 1700, this time together with "Good Night and God be with you all, Or the Neighbours Farewell To his Friends" (Roxburghe 3.672 at EBBA, text also reprinted in Roxburghe Ballads VI, p. 235 ). Around the same time another printer offered a broadside called The new way of Love is he cause of my Mourning. To it's own Proper Tune (no imprint, c. 1700, Wing N792A at EEBO, now also NLS Rare Books I.262 95, at EBBA). But here the text was completely different and had nothing to do with the original topic:

|

|

|

- When Strephon the heart of fair Iris possest,

'Mongst all the young Sheherd's she loved him the best

No swain in a mistress so fully was blest,

For he was both her Friend and her Lover;

[...].

|

|

|

The first "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" was not printed again during the 18th century but interestingly "The Forlorn Lover" remained popular and was republished with a different woodcut and some minor edits in the text ca. 1730 in Newcastle (Roxburghe 3.324-325 at EBBA) by John White (see Archaeologia Aeliana 3/3, 1907, p. 124) and then ca. 1750 in London (ESTC N025363 at ECCO).

III.

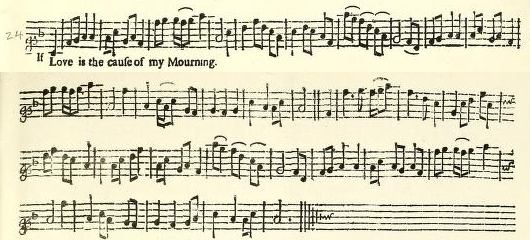

What was the original melody for this song? Two broadsides published after "The Forlorn Lover" referred to a tune called "The Week Before Easter":

- The Master-piece of LOVE-SONGS. / A Dialogue betwixt a bold Keeper and a Lady gay [...] To the Tune of, The week before Easter, the days long and clear, London 1685 (Pepys 2.249v at EBBA )

- The Seamans Renown in Winning his Fair Lady [...] Tune of, A Week before Easter, London, between 1678 and 1688 (Roxburghe 3.120-121 at EBBA, also in Roxburghe Ballads VII, p. 559)

But a tune with that name is nowhere to be found and has to my knowledge never been printed. So this is not of much help. But there was one called "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" and it's not unreasonable to assume that it was used for the ballad with the same name and also possibly for "The Forlorn Lover". The earliest version can be found in the Atkinson Manuscript (see Wikipedia) a fiddle tune book from Northumberland that was compiled in 1694/95 (p. 147-8, available at at FARNE; also SITM I, No. 144, p.30):

According to John Glen (p. 93) it was "also included in a manuscript flute-book [...] dated 1694". This tune was first published 1700 in Henry Playford's Original Scotch Tunes (p. 10-11):

|

If it was in fact an "original Scotch tune" then it's not implausible that song itself had also been written in Scotland and then migrated to England where it then served as the model and inspiration for "The Forlorn Lover". It should be noted that it was reprinted with another popular Scottish song, "Good Night and God Be With You All, Or The Neighbours Farewel To His Friends" on the broadside published in 1700 (Roxburghe 3.672 at EBBA). This text had also been first published circa 1670 (see Copac) - according to another dating even earlier, in 1654 (Wing N414B, available at EEBO, see Copac) - and the first editions of both "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" and "Neighbours Farewel" look as if they come from the same printer's press. Maybe these two songs had traveled together from Scotland to London and in this case - if the earlier date for "Neighbours Farewell" is correct - it is also possible that "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" was first printed ca. 1654.

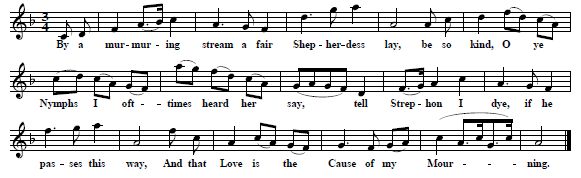

In 1724 Allan Ramsay published another text for this song in the first edition of his Tea-Table Miscellany (p. 32):

|

|

|

- By a murmuring Stream a fair Shepherdess lay,

Be so kind, O ye Nymphs, I ofttimes heard her say,

Tell Strephon, I dy, if he passes this Way,

And love is the cause of my mourning.

False shepherds that tell me of Beauty and Charms,

You deceive me, for Strephon's cold Heart never warms;

Yet bring me this Strephon, let me dy in his arms;

O Strephon the Cause of my mourning.

But first, said she, let me go

Down to the Shades below,

E'er ye let Strephon know

that I have lov'd him so;

Then on my pale Cheek no blushes will show,

That love is the cause of my mourning.

Her Eyes were scarced closed when Strephon came by,

He thought she's been sleeping, and softly drew nigh;

But finding her breathless, Oh Heavens, did he cry,

Ah Chloris the cause of my mourning.

Restore me my Cloris, ye Nymphs use your Art,

They sighing, reply'd, 'Twas yourself shot the dart,

That wounded the tender young Shepherdess Heart,

And kill'd the poor Chloris with mourning.

Ah then is Chloris dead,

Wounded by me! He said,

I'll follow thee, chaste Maid,

Down to the silent shade:

Then on her cold Snowy Breast leaning his head,

Expir'd the poor Strephon with mourning.

|

|

|

The author of these words is not known. According to an unsubstantiated rumour they were written by Duncan Forbes (1685-1747), later Lord President of the Court Of Session. Robert Burns once claimed "that the verses were composed by a Mr R. Scott, from the town or neighbourhood of Biggar" (William Stenhouse, note in Johnson, Scotish Musical Museum, Vol. 2, ed. from 1839 , p. 113, at Google Books).

The new text has nothing to do with the lyrics of the original "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning", only the structure and the rhyme scheme were retained. Strephon was the protagonist of many songs from the 17th and 18th century (see for example "Strephon And Cloris", Pepys 3.191 and "The Surprized Shepardess", Pepys 3.199, both at EBBA) and this kind of pastoral dramas were immensely popular. In 1725 William Thomson published text and tune in his Orpeus Caledonius (No. 17, p. 34 in the second edition, 1733):

|

The song was very popular throughout the 18th century. It was included for example in songbooks like The Musical Miscellany (London 1730, p. 42-44) and Calliope, Or, English Harmony (London 1739, p. 96). Joseph Mitchell used the tune in his ballad opera The Highland Fair (1731, Air XXV, see also abcnotation.com) and it can also be found in James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion (Vol. 1, London 1745, p. 27) and William McGibbon's Collection Of Scots Tunes (Vol. 3, London, ca. 1750, p. 64, see Fiddler's Companion). The text was reprinted regularly in songsters like The Hive. A Collection Of The Most Celebrated Songs (Vol. IV, London 1732 , p. 133) and The Blackbird (London 1783, p. 103) and at the end of the century the song was reprinted in both The Scots Musical Museum (Vol. 2, Edinburgh 1788, No. 109, p. 111) and David Sime's Edinburgh Musical Miscellany (Vol. 2, Edinburgh 1793, p. 332; all links to the Internet Archive & Google Books):

At this point it may be possible to reconstruct the song's early history. It is not entirely convincing because of a deplorable lack of additional information. But this is the best I can come up with at the moment. It seems that "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" was originally a Scottish song. It is not unlikely that an earlier unprinted version had used the title line as the refrain in every verse.

In the 1670s - perhaps even earlier, around the year 1654 - this song must have been known in London where it first served as the blueprint for "The Forlorn Lover". The anonymous writer of that ballad borrowed most of the original verses, rewrote them a little bit and also added some more stanzas. It's not clear if the original melody was also used for this new version or if it was really sung to "a pleasant new tune".

At the turn of the century someone wrote a completely new text that was published as "The new way of Love is the cause of my Mourning" but this version sank without any trace. The next new version was much more successful - maybe because it was published by both Ramsay and Thomson in 1724/5 - and was reprinted regularly during the 18th century. The original song vanished from the market after 1700 because it was replaced by both "The Forlorn Lover" and the new "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning". In fact these two offsprings had a much longer lifespan than their predecessor.

IV.

"The Forlorn Lover" was last published in 1750. Already ten years later a new version came out, this time radically shortened to only five stanzas. It seems that the old long ballads were out of fashion at that time and listeners had much less patience:

- The Constant Swain And False Nymph. A New Song, London?, ca. 1760 (ESTC T031624, available at ECCO, also in: The Marybone [sic!] Concert : Being a choice collection of songs, sung this and the last seasons, at Vauxhall, Ranelaugh [sic!], and Marybone, and other places of entertainment, Printed and sold in Aldermary Church Yard, Bow Lane, London, ca. 1760)

|

|

|

- I courted a Lass that was handsome and gay,

I hated all people that against her did say,

I thought her as constant and true as the day,

But now she is gone to be married.

When that I saw my love to the church go,

The bride and the bridgegroom they made a fine show,

I soon followed after with a heart full of woe,

To see how my love she was guarded.

When that I saw my love sat down to meet,

I sat myself down by her, but none could I eat,

I loved her sweet company better than meat,

Altho' she was ty'ed to another.

When that I saw my love stand all inwite

With tears in my eyes how she dazzled my sight,

I pull'd off my hatt and bid her good nigh

Adieu to false lovers for ever.

Dig me a grave both wide long and deep

And strow itall over with flowers so sweet,

There will I lay me down and take a long sleep,

And that's the best way to forget her.

|

|

|

The text was reprinted 13 years later in:

- The New Pantheon Concert. Being A Choice Collection Of The Newest Songs, sung this and last season at the Pantheon, Vauxhall, Renelaugh [sic!], and other places of Entertainment, Printed and sold in Aldermary Church-Yard Bow Lane, London, ca. 1773 (ESTC T012268, available at ECCO)

Unfortunately we don't know which tune was used with this "new" old song because it was never published with music. But at least we know from the titles of these two songbooks that this variant was sung by professional singers at the pleasure gardens and concert halls.

The text is clearly based on "The Forlorn Lover" but it's not a fragment, it works well as a song in its own right and the editor - whoever it was - did a good job. The first three verses of the ballad text were dropped. They had served as a kind of introduction to the story. Instead we see here for the first time the modern version of the first verse. It's a combination of the first line of the fourth verse and the the second line of the fifth verse:

This is paraphrased with different words, presumably to get a correct rhyme:

I courted a lass that was handsome and gay,

I hated all those that against her did say

The second, fourth and fifth verse are clearly based on verses 7, 10 and 11 of "The Forlorn Lover" although there are some variations, for example in the second half of the second verse:

This sounds nearly as clumsy as the corresponding lines in both "The Forlorn Lover" and "Love Is The Cause of My Mourning":

I laughed in conceit but my heart was full low

To see how highly she was regarded

My heart was so grieved I mourned for woe

To see her so lowly regarded

The third verse of "The False Nymph" is new and has no parallels in "The Forlorn Lover". It also sounds a little bit clumsy, especially the line "I lov'd her sweet company better than meat". But I presume the "meat" was used because it rhymed with "meet" and "eat". "Dig me a grave [...]" works quite well at the end of the song as it reflects the narrators disappointment and resignation.

It took quite a long time until the next version was published

- The False Hearted Lover, Printed by W. Pratt, Birmingham ca. 1850 (with another song called "Cold Blows The Wind", Johnson Ballads 1436 at BBO

|

|

|

- I courted a bonny lass many a day,

I hated all people who against her did say,

But now she's rewarded me well for my pains,

She has gone to be tied to another.

Then I saw my love to the church go,

With the bride and the bridgegroom they cut a fine show,

Then I followed after with a heart full of woe,

To see my love tied to another.

The parson that married them aloud he did cry,

And you that forbid it I'd have you draw nigh,

I thought to myself I'd a good reason why,

Though I had not the heart to forbid it.

Then I saw my love in the church stand,

With a ring on her finger and glove in her hand,

I might have enjoyed her with houses and land,

But now she is tied to another.

When I saw my love sit down to meat,

I sat myself by hwer but nothing could eat,

I thought her sweet company better than meat,

Although she was tied to another.

But when I saw my love all dressed in white,

The ring on her finger it dazzled my sight,

I picked up my hat and I wished them good night,

Here's adieu to all false hearted lovers.

Then dig my grave, long white and deep,

And strew it all over with flowers so sweet,

That I may lay down and take a long sleep,

And that's the best way to forget her.

|

|

|

According to Roy Palmer (Birmingham Ballad Printers, Part Two: K - P ) William Pratt was busy from the 1840s until 1861 and it seems he was "the most prolific of the Birmingham ballad printers".

This new text is clearly based on "The False Nymph" and has retained some of its innovations. All the five verses of the precursor are included although some were edited a little bit. For example in the first verse "handsome and gay" is replaced by "many a day", a return to a phrase known from both "The Forlorn Lover" and "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning". But the third line of the first verse is completely new. And the phrase "tied to another" - introduced anew in the third verse of "The False Nymph" - is now used as the last line of this one and three other verses.

The two new verses weren't exactly that new. The third about "the parson that married them" recycles one from "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning".

When that I did hear the Clerk publickly cry,

Is there any contrary, its time to draw nye,

I thought in my mi[n]d good reason had I.

but yet it was best to conceal it.

For some reason the other new verse - the fourth - is closer to one from "The Forlorn Lover":

But when I saw my love in the Church stand,

Gold Ring on her Finger, well seal'd with a hand:

He had so seduc'd her with house and with Land,

That nothing but Death can them sever.

Here we have already the bride standing in the church, the "gold ring on her finger" and also "houses and lands". The ring appears again in the penultimate verse and replaces the "tears in my eyes".

This was the last English version but interestingly another Scottish variant - now with nine verses - was published towards the end of the century:

- It Was Not My Fortune To Get Her, published by the Poet's Box in Dundee between 1880 and 1900 (with three other songs on the same sheet; available at The Word on The Street, National Library Of Scotland)

|

|

|

- I courted a lassie for many a long day,

And hated all persons that against her did say ;

Now she has rewared me by saying "nay,"

For she's going to be wed to another.

The clerk of the session he gave a loud cry,

If any have objections I pray bring them nigh,

Thinks I to mysel' objections have I,

But it wasna my will to affront her.

When I saw my bonnie love to the church go,

With bridegroom and maidens she made a fine show,

While I followed after with a heart full of woe,

To see how my false love was guarded.

When I saw my bonnie love at the kirk-stile,

I tramped on her gowntail but did'na it file,

She turned round upon me and gave a slight smile,

Saying, young man you've troubled for nothing.

When I saw my bonnie love in the church stand,

The ring on her finger, the glove in her hand,

Thinks I to mysel beside her I should stand,

But it was not my fortune to get her!

When I saw my bonnie love sit down to dine,

I took up the glass and I poured out the wine,

Drink health to the bonnie bride that should have been mine,

But it was not my fortune to get her.

When I saw my bonnie love in her bed laid,

'Mang white sheets and blankets sae neatly downspread,

Wished that I was the young man 'twas to lie by her side,

But it was not my fortune to get her.

O, bridegroom, O bridegroom! I'll tell you a guise,

I've lie'n wi' your bonnie bride ay oftener than thrice,

And she daurna deny it on the bed where she lies,

So she's 'but my old shoes when you've got her.

But now she is off and away let her go,

I'll never give over to sorrow and woe,

But I'll cheer up my heart and aroun' I'll go,

And hope I will soon find another.

|

|

|

This new text is at least partly based on "The False Hearted Lover" and uses four of its seven verses although sometimes with interesting changes. For some reason the third verse reintroduces the wording from "The False Nymph":

A new line - never printed before - becomes the last phrase in three verses and also the title of the song:

The seventh verse where the "bonnie love" is "in her bed laid" isn't completely new, it's a motif already known from "The Forlorn Lover":

But when the Bride-Maidens were having her to Bed,

I stept in amongst them and kissed the Bride:

I wisht I might have been laid by her side,

And by that means I got me a favor.

There are four completely new verses that can't be found in any of the earlier commercial versions (4, 6, 8. 9). Most interesting is the new ending. This time the protagonists doesn't long for his grave as in the preceding variants. Instead he first spoils the festive mood of the wedding ceremony by confessing to his rival that he had "lie'n wi' your bonnie bride ay oftener than thrice" and denouncing her as "my old shoes". And then, after he had his revenge on both the bride and the bridegrom, hopes to " soon find another".

So we have five different versions of this song printed between ca. 1670 and 1880. The longest is a ballad of sixteen verses, the shortest a Popular song with only five. The first and the last were from Scotland and the other three from England. But all three English texts must have been known in Scotland because the broadside text published by the Poet's Box in Dundee has preserved traces of all of them.

All versions since "The Forlorn Lover" are based on the preceding text and but they also offer variations as well as new lines and verses. It seems that the song was always modernized in accordance with the tastes of the prospective buyers. Unfortunately we don't know who has written these texts. It could have been an anonymous street poet hired by the printers to construct "new" songs by plundering ancient broadside sheets. But it is also possible that some of these texts were taken down directly from contemporaneous performances of this song.

V.

The song in its different versions remained in print for more than 200 years and it must have been quite popular . The first one to publish a variant from oral tradition was David Herd (1732 - 1810), the Scottish anthologist and antiquarian. It can be found in the second edition of his Ancient And Modern Scottish Songs (Vol. 2, p. 5). Here the song is still called "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" and this phrase also serves as a refrain for four of the five verses. It is not known where and when Herd has collected this text - it shows traces of all three commercial version printed so far - but it's more or less a fragment and not a complete song.

|

In 1867 the Irish folklorist, collector and storyteller Patrick Kennedy (1801 - 1873, see answers.com) published his book The Banks Of Boro. A Chronicle Of The County Of Wexford. This autobiographical novel about life in Ireland during the years 1817 and 1818 offers fascinating accounts of ballad sessions and he quotes the words to 25 songs of all kinds that were popular at that time. Among them is a fragmentary version of "The Forlorn Lover" that also includes the third verse from the "False Nymph" (p. 340-1, at Google Books, text reprinted in The Universal Irish Songbook, New York 1884, p. 96, at the Internet Archive ). It is performed here by one Charley Redmund, "one of the young assistants, a most restless and good-humoured individual" (p. 12), who was asked to sing his "best song":

"I'll sing you a song which I think has come to us from England with other things some better and some worse I learned it from a servant boy that was born under the hill of Camross between Clonroche and Taghmon. It has a very fine air if I could only master it. You may call it 'The Rejected Lover'":

Kennedy wrote his book nearly 50 years after he had heard it but "it was important to him to represent accurately the kind of songs popular in Wexford" at that time (Cohane/Goldstein p. 427). At least the text looks like a variant from before 1820 and I see no reason to doubt its authenticity.

The song was also part of the repertoire of Agnes Lyle (ca. 50), a weaver's daughter and ballad singer from Renfrewshire in Scotland. In 1825 William Motherwell wrote down a number of the ballads known to her and published them in his Minstrelsy Ancient And Modern (1827). His manuscripts later became a major source for Francis Child. Unfortunately Motherwell only noted the first verse and never managed to secure a more complete version (text quoted from McCarthy 1990, p. 43):

|

|

|

- The week before Easter the day long and clear

The sun shinng bright & cold frost in the air

I went to the forest some flowers to pull there

But the forest could yield me no pleasure.

|

|

|

John Clare (1793-1864, see Wikipedia & PeteCooper.com) , the peasant poet and fiddler from Northampton-shire also knew this song. His father, a disabled pauper living on a little allowance from the parish (Cherry 1873, p.1, at Google Books), could read a little bit and loved the cheap song sheets sold at the local fairs (Martin 1865, p. 35, at the Internet Archive). But he also was a singer with a great repertoire of songs and a "tollerable good voice, & was often called upon to sing" at the local inn (Deacon 1993, p. 22). Clare grew up with these kind of songs and later started to collect them both from his parents and other local sources. By all accounts he did most of his collecting in he 1820s and he "probably stands as the earliest collector of the songs people actually sang in Southern England" (Deacon, p. 18). In one manuscript he later described his experiences as a ballad hunter. This is worth quoting in full because it shows the same nostalgia for the good old days and the disdain for modern Popular songs that was common among Folk song collectors of later generations (quoted from Cherry, p. 323):

"I commenced sometime ago with an intention of making a collection of Old Ballads, but when I had sought after them in places where I expected to find them, namely, the hayfield and the shepherd's hut on the pasture, I found that nearly all those old and beautiful recollections had vanished as so many old fashions, and those who knew fragments seemed ashamed to acknowledge it, as old people who sung old songs only sung to be laughed at and those who were proud of their knowledge in such things knew nothing but the senseless balderdash that is bawled over and sung at country feasts, statutes, and fairs, where the most senseless jargon passes for the greatest excellence, and rudest indecency for the finest wit. So the matter was thrown by, and forgotten until last winter, when I used to spend the long evenings with my father and mother, and heard them by accident hum over scraps of the following old melodies, which I have collected and put into their present form."

According to George Deacon (pp. 93-97) four versions can be found in Clare's manuscripts. One - in Northampton Ms. No. 18 - was published in 1873 by J. L. Cherry in his Life And Remains Of John Clare (p. 324-5).

This is the most elaborate version of the song so far, in fact it seems to me that it was written with much more care than the three broadside texts. In the manuscript it is described as an "Old Song - Fragments gathered from my Father & Mothers singing - & compleated" (quoted by Deacon, p. 94). Lines, phrases and words from both "The Forlorn Lover" and "The False Nymph" are clearly recognizable but it is obvious that the text was heavily edited by John Clare himself. Three verses (5, 6, 10) can't be found in any other variant of this song and I am pretty sure that they were written by Clare (see also Deacon, p. 97).

Two other texts are very similar to this one (in Peterborough Mss. B4 & A 40, see Deacon p. 93 - 95) with only some minor variations but two more additional verses (9 & 11) that I haven't seen anywhere else. I don't doubt they were also fabricated by Clare. The fourth text (in Peterborough Ms. B7, quoted from Deacon, p. 95-6) is surely the earliest version, the one Clare had learned from his parents. In the manuscript this variant is called "An old Ballad copied from my mother & fathers memory with some few touches at correction" (quoted by Deacon, p. 94):

|

|

|

- The week before Easter, the days long and clear,

So bright shone the sun and so cool blew the air,

I went in the meadow some flowers to find there,

But the meadow would yield me no posies.

I went in the meadow one hour for to spend

& for to come back again was my intent

I heard a young man so sorely lament

Saying love was the cause of my mourn

I saw my false love to the merry church go

The bride men & maidens they made a fine show

I laughed in my mind tho my heart it was woe

Let her go I shant forget her

I saw my true love in her bride bed at night

My eyes filld with water then dimmed my sight

I doffed off my hat & I bade her good night

So adieu to my false love for ever

Dig me a grave long wide and deep

& strew it all over with flowers so sweet

Lay a sod at my head & another at my feet

& adieu to my false love for ever

[Or: Thats the right way to forget her]

I courted a girl that was handsome & gay

I hated all them that against her did say

I thought her as constant & true as the day

But now she is gone to be married

When that I saw my love to the church go

The bride men & maidens they made a fine show

I laughd in my mind tho my heart it was woe

To see how my false love was guarded

When that I saw my love in the church stand

With her ring on her finger & her love in her hand

Now shes enjoying both riches & land

He must take her since I cannot have her

When that I saw my love sit down to meat

I sat myself by her but nothing could eat

I thought her sweet Company better than meat

Altho she was tyed to another

|

|

|

The first five verses as well as the eighth are clearly derived from "The Forlorn Lover" (1, 3, 7, 10, 11, 8), a variant of the fourth can also be found in "The False Nymph". The third line of the second verse has even retained the wording used in the old "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning":

[...]

When for to turn back again was my intent,

I heard a young Man who sore did lament;

for love was the cause of his mourning.

The fifth verse where the narrator is longing for his grave is given with two different variants for the last line: the one from "The Forlorn Lover" ("Adieu to my false love for ever") and the one from "The False Nymph" ("Thats the right way to forget her"). Next is the first verse of the latter song and then the third stanza is repeated, this time also with the last line from "The False Nymph" ("To see how my false love was guarded"). This variant then closes with one more stanza taken directly from that text, the one where the narrator claims that "her sweet Company [is] better than meat".

These nine verses with the two alternate lines are in fact the remnants of two songs. There are six of the sixteen verses from the old broadside text of "The Forlorn Lover" as well all five from "The False Nymph" . This means that both versions were still known in the 1820s although the former - last printed in 1750 - only in a rather mutilated form

But it also shows that even more or less illiterate people from the countryside were familiar with songs from printed sources and - at least in this case - rarely deviated from the original text. Maybe Clare's parents had learned these songs in their youth although it is not unlikely that at least his father had actually seen song sheets with these texts.

In 1832 Henry Incledon Johns (1776-1851) from Devonport, first a banker and then a professor for drawing (see Wright 1896, p. 275, at the Internet Archive; Dare & Hardie 2008, p. 197, at Google Books) published a little book with a long title:

- Poems Addressed By A Father To His Children : With Extracts From The Diary Of A Pedestrian; And A Memoir Of The Author, Devonport 1832

It includes an interesting report about a night spent in a pub near Dartmoor with a group of farmers (here quoted from a note in the manuscripts of Sabine Baring-Gould, SBG/3/1/479 at the EFDSS):

"One of the party [...] never took any share in the conversation, but appeared to have been invited there for the sole purpose of singing to them. He sang a great number of ballads making up in loudness for what he lacked in melody [...] his auditors continued to talk while he sang [...]"

The singer "was a pauper" - like John Clare's father - and over 70 years old. One of the songs he performed started with:

"A bonny lass I courted full many a long day,

For dearly I loved to be in her sweet company."

The lover then describes the the progress of his suit, which proves unsuccessful, & concludes thus:

"Go dig me a pit that is long, large and & deep,

And I'll lay myself down to take a long sleep,

and that is he way to forget her"

These few lines are mostly derived from "The False Nymph". But in the first line the old phrase "many a long day" from "The Forlorn Lover" is reanimated. This is closer to the broadside text of "The False Hearted Lover" that was only published much later.

Even literary works can offer some interesting information. In 1864 a book called Rubina by an anonymous writer was published in New York. This is the story of an orphan girl who, after the death of her mother, has to live with her aunt's family. One of the story's protagonists is Debbie, the housemaid. At one point the children hear her "wailing through an old song" in a "mournful tone" (p. 201-2, at the Internet Archive)

This are two verses from "The False Nymph", only the last line is a variant form of the old phrase "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" known from the two oldest versions that for some reason has survived. It is not unreasonable to assume that the author had heard it in his - or her - childhood and again I see no reason to doubt its authenticity. Interestingly it is the only known variant of this song from the USA.

VI.

At this point we have one Scottish variant from the second half of the 18th century as well as five from the first half of the 19th century: one from Ireland, one from Scotland, two from England and one from the USA. This is not much but at least it shows that the song was known by the people and part of the repertoire of rural singers. But it seems it was also known among the more educated classes. In 1869 a line was even quoted by Joseph Sheridan LeFanu in his novel The Wyvern Mystery (p. 161, at Google Books):

'I loved her sweet company better than meat,' as the song says.

All the texts are mostly fragments and all very similar to the printed versions with only few variations. Unfortunately we don't know the melodies used for these variants. The first tune can be found in the second volume of William Christie's Traditional Ballad Airs (1881, p. 134-5). Here the song was called "It Hasna Been My Lot To Get Her". Christie (1816 - 1885), Dean of Moray and Chaplain of the Duke of Richmond, had grown up in the county of Aberdeen. In 1844 he began writing down the ballad he had heard in his boyhood (Vol. 1, p. viii) and in 1876 the first volume was published. Most of the songs were heavily edited:

"It cannot [...] be considered a work unworthy of the effort of a Christian clergyman to give to his countrymen their ballads, accompanied with their beautiful Airs, and so purified that they can be sung in any company, from the drawing-rooms of the noble and wealthy to the firesides of the peasantry, without raising a blush on the face of the most modest Christian" (Introduction the first volume, 1876, p. vii).

The tune - "arranged from the singing of a farmer's daughter, a native of the Parish of Longside, Buchan" - is very different not only to the one used for "I Loved A Lass" but also to those of all the other variants collected later. For some reason it is in 4/4 time instead of the usual 3/4 or 6/8.

The text - "epitomized by the Editor" - can't have been that old when he wrote it down. This variant is clearly based on "The False Hearted Lover". That broadside had been published in 1850 and it must have migrated quickly to the Northeast of Scotland. Six of the ten verses (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9) are very similar to verses 1 - 5, 7 and 8 of the broadside text. There are some minor variations and it's not clear if these are Christie's edits or if they were already in the version sung by the "farmer's daughter".

|

|

|

- I courted a lassie for mony lang day,

And aye conter'd them that against her did say,

Bat now she's rewarded me by saying nay,

And she's to be wed to another.

When I saw the bonny lass a' drest in white,

Wi' tears in my een she dazzl'd my sight;

I thought wi' mysel' I could never be right,

Sin' it hasna been my lot to get her.

When I saw the bonny lass to the church go,

With her young men and maidens that made a fine show,

l followed after with heart füll of woe,

Sin' it hasna been my lot to get her.

When I pass'd the bonny lass in the church style,

I tramp'd on her gown though I didna it fyle;

She turned to me and said wi'a smile,

"Young man, ye are troubl'd about nothing."

Mess John of the parish he gave a loud cry,—

"If any object now, l pray they'll draw nigh;"

I thought wi' mysel' good occasion ha'e I,

For it hasna been my lot to get her.

When I saw the bonny lass in the church stand,

Wi' the ring on her finger and glove in her hand ;

I wish'd him that got her both houses and land,

Though it wasna my lot to get her.

Now after the wedding we sat down to dine,

I took up the bottle and served the wine,

And drank to the bride that should ha'e been mine,

Though it hasna been my lot to get her.

They a'got sae merry that I couldna byde;

I leant o'er the table, shook hands wi' the bride,

I bade her farewell, should ha'e been by my side,

And oh ! I was wae then to leave her.

Now yell dig my grave baith lang, wide and deep,

Put a stone at my head, a green turf at my feet,

And there I'll lie down and tak' a lang sleep,

And when I awake I'll think on her.

So they dug his grave baith lang, wide and deep,

Put a stone at bis head, a green turf at his feet,

And there he was laid down to tak' a lang sleep,

But he will tak' lang to think on her.

|

|

|

One phrase - "it hasna been my lot to get her" is used as the last line in five of the ten verses and it would later also appear in the Dundee broadside as "It was not my fortune to get her". The last verse - "dig me a grave [...] - is repeated, but the second time in the third person. Here the poor guy not only longs for his grave. In the end he really dies. MacColls "I Loved A Lass" has the same ending.

Christies version also includes three additional verses that can't be found in any earlier printed text. Two of them (4, 7) were later included on the broadside from Dundee and one of them - "[...] we sat down to dine [...] - is also part of "I Loved A Lass". This strongly suggests that at least some of the new stanzas from the broadside existed in oral tradition before they were printed.

In 1891 another English variant of this song called "The False Lover" was published in Songs And Ballads Of The West by the Reverends Sabine Baring Gould and H. Fleetwood Shephard (No. 97, p. 206-7). According to the notes "words and music [were] taken down from old Mary Satcherly by Mr. Shephard (p. xl) and from the notes to another song we learn that "Mary Sacherley [sic!], aged 75, perfectly illiterate" from Huccaby Bridge, Dartmoor was the "daughter of an old singing moor man" (p. xxxviii, at the Internet Archive).

The Reverend Baring-Gould (1834-1924, see also Songs Of The West ), a novelist but also an impressive and versatile scholar, was an industrious writer who published a great number of books. The aim of this collection of "old" songs from Cornwall and his native Devon was to save them from oblivion, preserve and revitalize them. His informants were "nearly all old, illiterate [...] and when they die the traditions will be lost, for the present generation will have nothing to say to these songs [...] and supplant them with the vulgarest Music Hall performances" (p. viii). The piano arrangements for the more educated musical enthusiasts were written by The Reverend H. Fleetwood Shephard who had also assisted him with collecting. He even organized concerts where these songs were performed and used the profits to help some of his singers "when suffering from accidents and the infirmities of old age" (p. xiii).

" It was [...] the most ambitious collection made to that date and the book set the pattern for the first folk revival at the end of the last century. The conventions devised by Baring Gould were to become the standard practice and, in particular, his recognition that the songs were linked to individual singers who were usually identified in the text" (Martin Graebe at Songs Of The West).

Of course many of the songs published in the book were edited by Baring-Gould, but in this case it is no problem. The original version of this variant as sung by Ms. Satcherly - or Satterly - and written down by The Reverend Sheppard can be found in his manuscript collection that is now available online at the Full English Digital Archive (SBG/3/1/476). He simply deleted two more or less redundant verses (4 & 6) and instead wrote a new one himself.

|

|

|

|

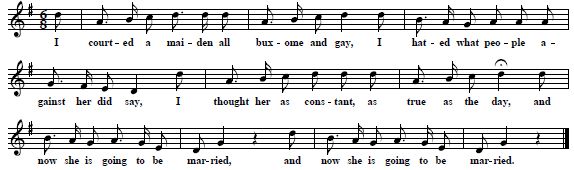

- I courted a maiden all buxome and gay,

I hated what people against her did say,

I thought her as constant, as true as the day,

And now she is going to be married.

O when to the church I my fair love saw go

I followed her up with a heart full of woe

and eyes that with tears and grief did overflow,

To see how my suit has miscarried

O when in the chancel I saw my love stan',

With ring on her finger, and true love in han'

I thought that for certain 't was not the right man,

although 't was the man she had wedded.

O when to her home I did see my love go,

I followed her up with a heart full of woe,

and eyes that with tears and grief did overflow,

To think with another she'd be bedded.

O when I my fair love did see in her seat,

I sat myself by her, but nothing could eat,

Her company, thought I, was better than meat,

although she was tied to another.

O when I my fair love saw to her bed go,

I followed her up with a heart full of woe,

I turned on my heel, I might [?] no [mo'] more

So adieu to my false-hearted lover.

[forgotten verse]

O make me a grave, that is long, wide and deep,

and cover me over with flowers so sweet,

That there I may lie, and take my last sleep,

For that is the way to forget her.

|

|

|

Interestingly in this version all the rhymes are correct, even the final lines of stanzas 1, 3 and 5 rhyme with their counterparts in the following verse. The text is clearly derived from "The False Nymph" and I don't see any influence from the broadside published in Birmingham in 1850. It is not unreasonable to assume that she had learned the the song in her youth from her father, a "famous singer" at Dartmoor (Baring-Gould, Ms. Vol. 1, p. 178, No. 86, pdf from the website Songs Of The West, p. 2).

In 1898 Kate Lee, secretary of the newly founded Folk-Song Society, met the the brothers James and Thomas Copper from Rottingdean, Sussex. One of them was the foreman of a farm, the other the "landlord of the 'Plough Inn,' a very small public-house" (Lee 1899, p. 10). They knew a great number of songs including one called "A Week Before Easter". This variant was published the following year in the very first volume of the Journal Of The Folk-Song Society (p. 23):

|

|

|

|

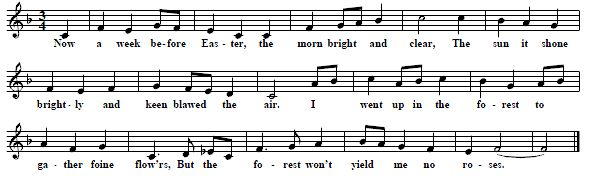

- Now a week before Easter , the morn bright and clear,

The sun it shone brightly and keen blawed the air.

I went up in the forest to gather foine flow'rs,

But the forest won't yield me no roses.

Now the first time I saw my love, she was dressed all in white,

Made my eyes (run and) water, she quite dazzled my sight,

But now she's gone from me, she showed me false play,

Now she's got tied to another.

The roses were red, and the leaves they were green,

And bushes and briars are pleasant to be seen,

Where the small birds were singing and changing their notes

Down amongst the wild beasts in the forest.

Now dig me a grave, both long, wide and deep,

And strow it all over with roses so sweet,

That I might lay down there, and take a long sleep,

And that's the right way to forget her.

|

|

|

This is a fragment of "The Forlorn Lover" with some lines from "The False Nymph". Of course there is not much left of the original song but it is still surprising too see that these verses had survived for so long as the text had been last published 150 years ago. Interestingly the tune is somehow related to the one of "I Loved A Lass". Here we can also find the characteristic stepwise movement from the tonic note to the fifth in the third bar.

The two brothers were made members of the Folk-Song Society. Later the´ Copper Family became a mainstay of English Folk Revival scene and they are still active today. Bob Copper (1915 - 2004), grandson of James, recorded this song a couple of times since the 50s, for example for the BBC in 1952 (Roud ID S194283) and for the LP A Song For Every Season (1971, at the Copper Family Website ).

These three variants published between 1881 and 1899 all have tunes strikingly different from each other. None of them is in any way related to the old "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" and only one of them has some similarities to the melody of "I Loved A Lass". But they also represent different stages of the song's development that existed side by side at the end of the 19th century.

VII.

In the early years of the 20th century English Folk song collectors found some more variants of this song. Alfred Williams noted that it was an "old favourite, formerly widely known" (see Wiltshire Folk Songs). Cecil Sharp wrote down at least seven versions in Somerset and Oxfordshire (now available in Karpeles, Sharp Collection I, No. 59, pp. 268-272). Other collectors like Ralph Vaughan Williams (see Palmer 1979, p. 152-3), Anne Geddes Gilchrist, H. E. D. Hammond, Janet Blunt, George Butterworth and George Gardiner were successful too (see the manuscript collections at the Full English Digital Archive). At that time these kind of songs were long "out of fashion" and "the practice of singing folk songs had very largely gone underground". Most of the informants were old people who still "remembered them [but] were shy of singing them for fear of ridicule by the younger generation" (Karpeles, Sharp Collection I, p. ix).

Sharp published three variants in 1905 in the Journal Of The Folk-Song Society (Vol. 2, p. 12-14), one of them from the singing of Mrs. White from Hambridge, Somerset:

The words of this version are a mutilated fragment of the "False Hearted Lover" from the broadside published ca 1850. For some reason Sharp also included this variant in 1906 in the first volume of his Folk Songs From Somerset (No. XX, p. 40-1), an influential collection that was aimed at bringing Folksongs back to the Folk, especially to the children in school. It later also found its way into The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs (1959) and was then recorded in 1960 by A. L. Lloyd for the LP A Selection From The Penguin Book Of English Folk Songs (Collector JGB 5001).

Interestingly the first verse of "The Forlorn Lover" had survived in a couple of these English variants, for example in this fragment of two verses collected by Janet H. Blunt in Oxfordshire in 1916. She heard it from Mrs. Jem Lines, aged 83 (JHB/1A2 at the Full English Digital Archive). Her tune has some similarities to the one used for "I Loved A Lass":

|

|

|

- The week afore Easter, the day's long and clear,

Bright shine the stars, and cold blows the air.

I went to the forest, not long time to stay there,

Because they wouldn't give me no posies

O! dig me a grave as is long, wide, and deep.

And stroll it with roses so love and so sweet.

I'll lay myself down, and take a long sleep.

And that's the right way to forget her.

|

|

|

The second verse is not from "The Forlorn Lover", it is from either "The False Nymph" or the "False Hearted Lover". So these two verses have different "time stamps". Another fragment consisting of four verses was recorded in Gloucestershire in 1907 from 76 years old Henry Thomas (Sharp Collection No. 59C, p. 271, text also in H. E. D. Hammond's notebook: HAM/3/13/15 at the Full English Digital Archive):

|

|

|

- Three weeks before Easter the day long and clear

Bright shines the sun and cold blows the air.

I went into the forests some flowers to find,

But the forest no posy would behold me.

I courted a bonny lass many a long day,

I hated all others against her did say.

But now she's rewarded me well for my pain,

She's going to be tied to some other.

When I saw mylove to the church go

With her bridesmaids and bridgegrooms she cut a fine show.

And I followed after with my heart full of woe

To see how my false love was guarded.

The I saw my love all in the church stand

With a ring on her finger and love in her hand.

Thinks I to myself you have houses and land

And I that am here have got neither.

|

|

|

Verses 2, 3 and 4 are clearly derived from the "False Hearted Lover" except one line ("To see how my false love was guarded") that can be traced back to "The False Nymph". So this is a variant that includes elements from three different printed versions. Other texts collected at that time show the same mixture of sources (see for example GG/1/12/716, p. 3; AGG/8/72, tune AGG/3/6/23; HAM/5/35/14, p. 5, all 1907, at the Full English Digital Archive).

Another variant from Sussex (AGG/8/22, tune AGG/3/6/3a, at the Full English Digital Archive) doesn't include the "week before Easter" but instead refers to another ancient line:

|

|

|

- Oh, once I loved a pretty girl, and as I do stile;

I hated all people and wished them ill,

And ain't I rewarded for what I have done,

For now she's the bride to another.

The first time I saw my love, to the church she was going,

The bridgegroom, the bridesmaids, cutting a fine show;

I quickly followed after, my heart full of woe,

To see how my false heart regarded.

[3 more verses]

|

|

|

The second line of the first verse looks like a corrupted form of a line from the fifth verse of "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" that was last printed in 1700:

I hated all those that wished her ill

The rest of the song is mostly made up of elements from both "The False Nymph" and the "False Hearted Lover".

A variant from Somerset written down by Cecil Sharp in 1907 (Sharp Collection I, No. 59A, p. 268, from William Tucker, 65) doesn't include any relics from the earliest versions. It's mostly based on the "False Hearted Lover", except the second part of the first verse that had survived from "The False Nymph":

|

|

|

- I courted a bonny lass many long day,

I striked all people against her did say:

I thought her so true as constant as day,

But now she is gone to get married.

O when did I see my love to the church go

With bride and bride maidens what made a fine show

I soon followed after with my heart full of woe,

Saying I am the man ought to had her.

When I did see my love in the church stand

With the ring on her finger and a bride at her hand

I thouight to myself that I should Ha' been the man,

But I had not the heart toforbid her.

The parson that married them aloud he did cry:

Comeall you forbidders, I'll have you draw nigh.

I thought to myself that's a good reason why,

For I had not the heart to forbid her.

When I did see my love sit up to meat

I sat down beside her but nothing could I eat.

I thought her sweet company was better than meat

Although she was tied to some other.

Now you dig me my grave both long, wide and deep;

Strow it all over with lowers so sweet,

That I may lay down and take my long sleep,

and that is the best way to forget her.

|

|

|

Now I don't want to dissect every variant but it helps to understand the song's history and the relationship between oral tradition and the printed versions. All these versions are made up mostly of verses derived directly or indirectly from the published texts. There are only minor additions and variations and in most cases these were only inserted because original lines or phrases had been forgotten.

"The Forlorn Lover" and "The False Nymph" had last been printed in 1750 respectively 1773. But these song must have circulated much longer in oral tradition as can be seen from the few variants and fragments that have survived from the first half of the 19th century. It seems that after the publication of "The False Hearted Lover" by Pratt in Birmingham many of the orally circulating versions were modernized: parts of the old texts were dropped and replaced with new lines and verses while some elements from the older versions were retained.

This was a kind of process of regularly updating and modernizing song texts after the publication of every new printed version. It also strongly suggests that in case of this song the variants from oral tradition were completely dependent upon published texts. It didn't matter much if the people could read or not or if they had access to the broadside itself and it also didn't matter much that "The False Hearted Lover" was only printed once in Birmingham. This new authoritative text must have been quickly available in other parts of the country. All these variants - with only very few exceptions like those collected by Baring-Gould and Kate Lee in 1890 respectively 1898 - were fragments of oral versions of this song from after circa 1850, the possible year of publication of the Birmingham broadside.

VIII.

The song was well-known in Scotland, too. It seems that it was more popular there than in England. As already noted a modernized version with some new verses was published in Dundee some time between 1880 and 1900, maybe even earlier. 17 variants from oral tradition were gathered by Gavin Greig and James Duncan between 1905 and 1914 in a comparatively small geographic area in the Northeast (now available in Greig-Duncan Collection 6, No. 1198, p. 310-327 ).

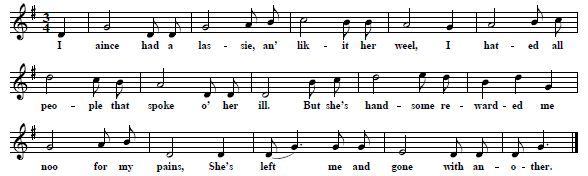

One of the longest and most complete variants was supplied in 1907 by Mrs. Harper, the wife of a schoolteacher from Cluny who had sent the collectors a lot of songs known by members of her family. This one was from the singing of her mother and her aunt. (Greig-Duncan Collection 6, No. 1198C, pp. 314-5 and notes, p. 568; 8, p. 565). The tune is loosely related to the one used for "I Loved A Lass":

|

|

|

|

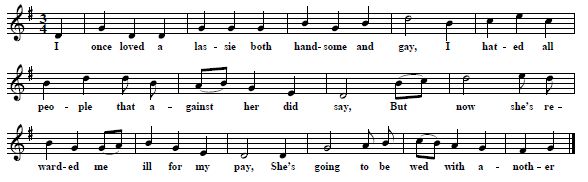

- I once lov'd a lassie both handsome and gay,

I hated all people that against her did say,

But now she's rewarded me ill for my pay,

She's going to be wed to another.

When I saw my bonnie love to the church go,

With bridegrooms and maidens she had a fine show,

And I followed after with a heart full of woe,

'Though it was not my fortune to gain her.

When I saw my bonnie love in the church stile,

I tramped on her gown tails but I did not them soil,

She turned her about and she gave a light smile,

Says "Young man, you are troubled about little."

When I saw my bonnie love in the church stand,

Wi' the ring on her finger and the glove on her hand,

Wished the man that has got her more houses and land,

'Though it was not my fortune to gain her.

The priest of the parish gave out a loud cry,

"If there's any objections l pray bring them nigh."

Thinks I to myself, good objections have I,

Though I had not a will to affront her.

When marriage was over and sat down to dine,

I sat down beside her and served out the wine,

I drank to the bonnie lass that should have been mine,

'Though it was not my fortune to gain her.

When marriage was over and sat down to meat,

I sat down beside her, but little could eat,

l loved her sweet company better than meat,

Though it was not my fortune to gain her.

When supper was over and all bound for bed,

When supper was over and all bound for bed

Wish'd I'd been the man was to lie by her side,

Though it was not my fortune to gain her.

But now she is gone and so let her go,

I'll never give over to sorrow and woe,

But I'll cheer up my heart and aroving I'll go,

For I'm young and I'll soon find another.

Out spake the bridgegroom, "Begone for a coward.

You've given too long on the edge of your sword,

You've widen to long in an unknow ford

So begone, for you'll never enjoy her."

"Hold your tongue, bridgegroom, I'll tell you a guise,

I've lain wi' your bonnie love oftener than thrice,

And she dare not deny it in the bed where she lies,

So you wear my old shoes when you've got her."

|

|

|

This text of this variant is very similar to the one on the broadside from Dundee as it includes all of its nine verses with only minor variations. The first verse is not exactly like the one from the broadside but a compilation of lines from four different printed versions. "I once loved a lass [...]" retains the wording from he oldest versions: "I lov'd a lass [...]" in "Love Is The Cause Of My Mourning" or "I loved a fair lady" in "The Forlorn Lover". The phrase "handsome and gay" is a relic from the "False Nymph". The second line had been used by the last three broadside texts. The third - "now she's rewarded [...]" - is known since "The False Hearted Lover" and the last is exactly as on the Dundee broadside.

There are two additional stanzas. The seventh is the "better than meat" - verse known from both "The False Nymph" and "The False Hearted Lover" but not used in the Scottish broadside text. The other - verse 10 - had never been printed before. Here the bridegroom orders his rival to leave. This is then followed by the verse known from the broadside where he is told that "you wear my old shoes when you've got her". This turns the éclat at the wedding into a heated discussion between the two men and makes it all much more livelier.

Another variant - "learnt from father and mother fifty-five years ago" - was supplied by James Duncan's sister in 1905 (GD 6, No. 1198B, p. 312-3, notes p. 565). It has not only a very similar tune but also the same set of verses with only minor variations. The only difference is that this text still ends with "dig me a grave [...]". But she also includes the new last verse known from the broadside ("[...] I'll soon find a better") and notes that "Father added this instead (his own composition)". This strongly suggests that the version from the Scottish broadside with the new ending already had circulated orally some time before it was printed in Dundee.

Most of the other variants collected by Greig and Duncan are very similar to these two and to the broadside text, although often much shorter and sometimes only fragments because verses had been forgotten (No. 1198, var. A, D, F, G, H, I, N, O, P, R, S, U). A version taken down in 1908 from Robert Reid, a shoemaker from Kemnay, looks like fragment of the Dundee broadside. Mr. Reid was himself very much interested in old songs. He had heard a lecture by James Duncan and in response sent him an article he had written for the Aberdeen Evening Gazette in 1897 about "Song In The Rural Districts of Scotland" where he had first published this text (No. 1198F, p. 318, Notes, p.565-6, Vol.8, p.521):

|

|

|

- I once had a sweatheart, she was handsome and gay,

I hated all people that against her did say;

But she has rewarded me ill for my pay,

For now she is wad to another.

I saw my false lovie unto the church go,

Wi' bridegroom and maidens, and they made a fine show,

While I followed after, with my heart full of woe,

To see how my false love was girded.

I followed my love unto the church stile,

I tramped on her gown tails, but did them no file:

She turned herself round, and wi' a light smile,

Say "You're troubled for nothing."

I saw my false lovie in the church all so grand,

Wi' the ring on her finger a and the glove on her hand;

I should be the man that by her side did stand,

But it wasna' my fortune to get her.

When the marriage was over and all down to dine,

I took up the bottle and I serbved out the wine;

And I drank to the bonny lass that should have been mine,

Tho' my heart it was almost a breaking.

But I'll cheer up my heart and a roving I'll go;

I will not give over to sorrow and woe;

I will not give over to sorrow and woe;

Nor fear but I'll soon find another.

|

|

|

These are six of the nine verses of the broadside text or six of the eleven verses used in the variants B and C with some minor variations and some garbled lines. Reid noted that he had "given them in much the same form as heard them sung between thirty and forty years ago" so this text also seems to predate the Dundee broadside.

But even if these variant had already existed in oral tradition before the publication of the Dundee broadside the published text must have had some influence, either directly or indirectly. It served as some kind of authoritative text that helped to extend the song's life-span and also stabilized the tradition. As in England the texts have also retained some relics from older printed versions. "The Forlorn Lover", "The False Nymph" and "The False Hearted Lover" must have been available in Scotland and they have heavily influenced oral tradition.

IX.

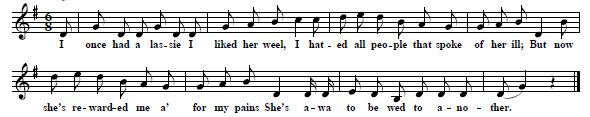

Now is the time - after this long trip through the song's history - to return to "I Loved A Lass" and discuss that particular variant. Ewan MacColl wrote in the liner notes to the Classic Scots Ballads that he had "learned the song from Miscellanea of the Rymour Club, Edinburgh". The Rymour Club was antiquarian society dedicated to the "collection [...] of ballads, lyrics, and other rhymed material, and of ballad and other tunes". Its findings were published in three volumes of Miscellanea between 1906 and 1926 (quote from Vol. 1, p. vi). The song can be found in Part V of Volume 1 (1910, p. 179-80, at Hathi Trust, also reprinted in Buchan 1984, p. 106, at Google Books). It was "noted from [the] singing" of Mr. A Briggs Constable, W. S. who had learned it from "John Henderson (now dead), of the firm of R. & T. Henderson, merchants, farmers, and fish-curers, of Spiggie, Dunrossness, Shetland [...] in 1885".

|

|

|

|

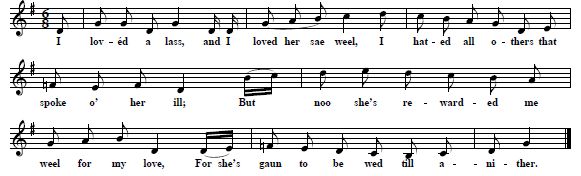

- I lovèd a lass, and I loved her sae weel

I hated all others that spoke o' her ill;

But noo she's rewarded me weel for my love,

For she's gaun to be wed till anither.

When I saw my love to the church go,

Wi'bride an' bride-maidens, they made a fine show;

An' l followed them on wi' a heart fu' o' woe,

For she's gaun to be wed till anither.

When I saw my love sit down to dine,

I sat down beside her and poured out the wine,

An' I drank to the lass that suld ha' been mine,

An' now she is wed till anither.

The men o' yon forest they askit o' me,

Hou many strawbcrries grew in the saut sea?

But I askit them back wi' a tear in my ee',

How many ships sail in the forest?

O dig me a grave and dig it sae deep,

An' cover it over with flowers sae sweet,

An' I'll turn in for to tak' a lang sleep,

An' may be in time I'll forget her.

They dug him a grave an' they dug it sae deep,

An' covered it over with flow'rets säe sweet,

An' he's turned in for to tak' a lang sleep,

An' may-be by this time he's forgot her.

|

|

|

As already noted the first two lines of the first verse are very old. They are very similar to some lines in stanzas 4 and 5 of "The Forlorn Lover".

I lov'd a fair lady [...] and I loved her well

I hated those people that spoke of her ill