Are you going to Scarborough Fair,

II. "Scarborough Fair" belongs to a family of songs that usually depict a dialog between a man and a woman who set each other insolvable tasks. It is more than 300 years old. Francis J. Child has subsumed this group in his English and Scottish Popular Ballads (1882) under No. 2, "The Elfin Knight" (Vol. 1, pp. 6-20). The earliest documented British variant is a long ballad of 20 verses on a black letter broadside that was printed circa 1670:

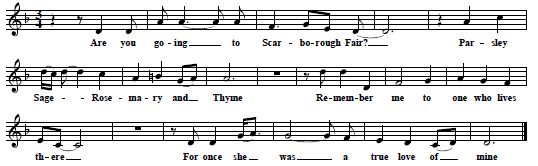

A version called "Cambrick Shirt" was first published in the 1780s in Gammer Gurton's Garland, a book of nursery songs and rhymes. Here we can find for the first time the now common refrain with the list of herbs as well as the "true lover of mine" in the fourth line (see the 1866 reprint of the edition from 1810, pp. 4-5). The messenger first appeared in a Scottish variant collected in the 1820s by ballad scholar William Motherwell (Child I, 2F, pp. 17-8) and in an American songsheet with the title "Love-Letter & Answer" published circa 1830 in Boston (available at America Singing: Nineteenth-Century Song Sheets, LOC, as108140). Here he is not yet going to a fair but shuttling between Berwick and Lyne in Scotland repectively Lynn and Cape Ann in Massachusetts. There is good reason to assume that he was introduced into this song much earlier otherwise this particular motif wouldn't have been spread so far already at that time. Since the 1880 folklorists both in Britain and in North America found numerous variants of songs from this family. The earliest known text of "Scarborough Fair" was published in 1883 in a newspaper, the "Leeds Mercury" (25.8.1883, Local Notes and Queries CCXLI). After an inquiry by Frank Kidson - who soon became one of the most respected authorities for old English songs - one correspondent sent in a more or less complete text and noted he had heard it "some twenty years ago" from a street singer. Kidson later published a slightly edited version of this text together with a melody of unknown origin in his Traditional Tunes (1891, (pp. 42-4). Between 1893 and 1916 three more variants of "Scarborough Fair" - all from a small area in the northeast of Yorkshire - were published in song collections, the last one by Cecil Sharp in his One Hundred English Folk Songs (No.74, p. 167, notes pp. xxxvi-xxxvii). They all had different tunes but none of them resembled the one associated with the modern versions of this song. That particular tune was introduced by Ewan MacColl who recorded his variant in 1957 for the LP Matching Songs For The British Isles And America (Riverside RLP 12-637, also available at YouTube). It was later also included in The Singing Island (1960, p. 26), an influential songbook compiled by MacColl and Peggy Seeger. According to the notes (p. 109) he had collected this version of "Scarborough Fair" in 1947 from "Mark Anderson, retired lead.miner of Middleton-in-Teasdale, Yorkshire" (p. 109). But he can't have collected much more than a tune and a fragmentary text because the greatest part of the words were lifted straight out of Kidson's book. MacColl wasn't the first to record his own version. Already in 1956 young American singer Audrey Coppard included it on her album English Folk Songs (Folkways FW 6917). According to the liner notes (pdf available at Smithsonian Folkways) she was in London in the early 1950s and played at club concerts "organized by A. L. Lloyd and Ewan MacColl, to whom she is indebted for introducing her to several of the songs in this collection". I assume that she learned "Scarborough Fair" from MacColl during that time. In 1959 English singer Shirley Collins also recorded the song for the LP False True Lovers (Folkways FW03564; also available at YouTube). Martin Carthy had learned the "Scarborough Fair" most likely from The Singing Island. He only edited the tune and the text a little bit and dropped three of the eight verses. But his arrangement was then borrowed by Paul Simon who recorded it himself in 1966 with his partner Art Garfunkel for their third LP, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary And Thyme. Their recording was also used in the movie The Graduate and included on the Soundtrack-LP. Since then this song was recorded countless times by all kinds of artists. One may say that it has never been more popular than today although it doesn't have much to do with what the songs from this family were all about. Their defining element always used to be the wit combat between the man and the woman. But this "discourse" has disappeared and what remained was a list of tasks without any inner coherence.

III. Dylan's debt to "Scarborough Fair" is regularly overstated and has been blown out of proportion. The melodies of both songs are very different from each other. Dylan only "retains elements of the 'Scarborough Fair' melodic contour and phrase structure for his new song" (Harvey, p. 33). The harmonic structure is changed, too and instead of the 3/4 or 6/8 meter he uses 4/4. In fact the differences are so great that it can be easily called an original melody. The lyrics are also for the most part Dylan's own. He has deleted nearly all of the motives of "Scarborough Fair" and only used the first verse as a starting point but then turns it into a song about nostalgia for an former love, a major topic in popular music. I wonder if he deliberately tried to write something like Scott Wiseman's "Remember Me (When The Candlelights Are Gleaming)" (1940). He was obviously fond of this song and there is a nice recording from East Orange 1961: Remember me when the candle lights are gleaming, Another closely related song is Jimmie Rodgers' ”My Old Pal” (1928): […] Dylan has retained the messenger. But he is not sent out to give the girl unsolvable tasks as in "Scarborough Fair". Instead he has to remind her of her former love. And that's another common motif in popular song. Examples predating "Girl Of The North Country" are Johnny Cash's "Give My Love To Rose", the Everly Brothers' hit "Take A Message To Mary" (B. & F. Bryant), both songs definitely known to Dylan. Also worth mentioning is "Tell Him I Said Hello" (Hagner/Canning, 1956), a song recorded for example by Betty Carter, that obviously inspired Dylan - as Andrew Muir has noted - when he returned to that topic for "If You See her Say Hello” (1974, Blood On The Tracks): When you see him If he asks you when I come and go The "north country fair" is of course an allusion to "Scarborough Fair", but here the messenger is not traveling to that fair but to the fair North Country. This inversion of noun and adjective makes the language sound somehow old fashioned (or he simply wanted to keep the rhyme fair/there). Surely there is also an autobiographical connotation but more important is the fact that in English songs songs the "North Country" is occasionally referred to as a land of pastoral beauty different and far away from the unpleasant modern towns, as in "The Northern Lasses Lamentation" (see for example Roxburghe 2.367, ca. 1675, at The English Broadside Ballad Archive): A North country lass [...] This contrast, although never explicitly stated in "Girl Of The North Country", is still there. It's a nostalgic juxtaposition of present and past by remembering the girl in the North Country he reconnects to this mythical place - which is obviously very different from the one in Dylan's "North Country Blues” (1963) - and searches for the lost youth. An interesting precursor using a similar set of motives is Dylan's "Ballad For A Friend” (1962). Here the singer is reminiscing about an old, deceased friend and the time he spent with him in a pastoral "North Country”: Sad I'm sittin' on the railroad track, [...] In verses 2 and 3 of "Girl Of The North Country" Dylan then paints an image of the girl. But it's surely not a "real" girl. It's an image of purity and innocence that sounds old fashioned and is based on archetypal male fantasies. In fact this girl is as mythical as the North Country. On the other hand this is the first instance of Dylan creating an image of an idealized woman, a topic he returned to later with more mature and opulent songs like "Love Minus Zero/No Limit" or "Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands". Asking the messenger to see if she "has a coat so warm to keep her from the howling winds" plays with the male instinct for protection. This motif is often either used jokingly, as in "Button Up Your Overcoat" (DaSylva/Brown/Henderson, 1928): Button up your overcoat, when the wind is free, Or else making love is proposed as the best means against the cold. Irving Berlin used this idea in his classic "I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm" (1936): The snow is snowing, the wind is blowing Other examples are Frank Loesser’s "Baby It’s Cold Outside" (1949) and Dylan's own "On A Night Like This" (1973). That song sounds in some way like an ironic return to some motives of "Girl Of The North Country". It reads as if the boy himself has returned to the North Country to keep the girl warm instead of sending someone else to see if she has a coat "so warm". [...] The girl's long hair, rolling and flowing "all over her breast" is another old fashioned, antique image, maybe directly taken from a fairy-tale book and already in use in the 19th century, for example in "Sweetly She Sleeps My Alice Fair" by Stephen Foster & Charles Eastman (1851): Sweetly she sleeps, my Alice fair, The first line in the the fourth verse of "Girl From The North Country" - "I'm wondering if she remembers me at all" - is clearly a paraphrase of line from either Scott Wiseman’s "Remember Me": It would be so sweet […] to know you still remember me or Jimmie Rodger’s "My Old Pal": I`m wondering [...] if you ever think of me But this motif can also be traced back to the 19th century, see for example John Greenleaf Whittier's "My Playmate" (1860). This is a poem about someone who is thinking about his childhood girlfriend, another work thematically related to "Girl Of The North Country": [...] Dylan's next three lines: [...] may have been inspired by line from a 1930 torch ballad, "Something To Remember You By" (Schwartz/Dietz), a song that is thematically related to (and may have been the starting point for the lyrics of) "Boots Of Spanish Leather": [...] Examples from the 19th century in a more florid language are (quoted from Vinson, pp. 31 & 51): I will be true to thee; If to dream by night and muse on thee by day, But all these three songs are about someone praying for the other one's well-being. Dylan's protagonist has only has prayed "many times" that she remembers him, which seems to me a little overblown. Nostalgia for a former love is a major topic of 20th century popular music. One of the most perfect examples is Johnny Mercer`s "I Thought About You" (1939): I took a trip on a train This is mature, grown-up nostalgia, songs about real people in an urban context. But I think that's not what Dylan intended with "Girl Of The North Country" although he freely borrowed from 20th century songs. Instead he made a trip straight back to 19th century nostalgia. If there is something that comes close in mood and in intent then it's a Stephen Foster song like "Voice Of The Bygone Days" (1850): [...] This song contains the major motives Dylan uses in "Girl Of The North Country": the evocation of the lost youth through nostalgia for an early love as well as the images of purity and innocence used to describe that girl. In the first half of the 60s Dylan tried to avoid the language and sentiments of the songs of the generation before and create something different. He used different strategies but in this case – as for example also in the verses of "Tomorrow Is A Long Time" – he circumvented the Berlin tradition by reanimating 19th century sentiments. Instead of becoming a new Johnny Mercer he "fosterisized" himself. But this helps to make the song special and to overcome its inherent sentimentality. Usually in 19th century songs and poetry it is an old man who remembers a dead (or - as in Greenleaf Whittier's "My Playmate" - an otherwise unreachable) girl: "The death of a beautiful woman is the most poetical topic in the world" (Edgar Allan Poe). The "Girl Of The North Country" is not dead. And the singer is no old man – although Dylan has experimented with the old man persona in some of his early songs and performances -, otherwise the messenger would be on the way to meet the granny in the north country. But by alluding to this ancient motif and transferring it into the 20th century he suspends the song from time and creates a air of timelessness and antiquity. This is a complicated process and I don't know if Dylan did it on purpose but the result he achieved is impressive. But the song's sentimentality is still obvious. In fact it is much more sentimental than for example Johnny Mercer's "I Thought About You". Dylan is walking on rather thin ice and only reading the lyrics on page without knowing the song might make some readers cringe. I presume that songwriters from the generation before would have regarded the lyrics as somehow corny and awkward. But Dylan manages to create an aura of authenticity that is essential for the song's effectiveness. Personal authenticity and communication between performer and listener on a personal basis are major assets of 20th century popular song. This was developed by singers, songwriters and musicians at least since the twenties with the rising importance of the new technical innovations like electrical recording, radio, microphone and movies. Singers were forced to create personalized singing styles and innovative songwriters like Irving Berlin quickly responded to this new challenges. Berlin's 20s ballads "imply a solitary listener" , his songs create a "lyrical 'space' [...] that is designed for the self absorbed, plaintative singer who inhabits it. The solitary consumer [...] inhabits the same space" (Philip Furia, p. 58). That is exactly the effect that Dylan achieves with "Girl Of The North Country" and many more of his love ballads. The only difference is that he has created a new – his own – authenticity. Singers like Crosby or Sinatra were as authentic to their audiences as is Dylan to his. One of the reasons for the popularity of Irving Berlin's love ballads in the 1920s was that his audience thought that they had grown out of his personal experiences. Of course he – like Dylan later, for example in his famous comment about "You're A Big Girl Now" not being about his wife – denied any autobiographical connotations. Authenticity is a matter of style, it's in no way universal. It is developed in interaction between the artist and his audiences. It's dynamic and permanently developed anew. Also the authenticity value of genres, performers or writers can change over time, as we can see for example in the history of Blues reception: revivalist listeners of today have completely different values than the original audiences. "Girl Of The North Country" is one of those songs of Dylan that can demonstrate in detail how he managed to build his own brand of personal authenticity and credibility as a singer and writer.

IV. - Authenticity of genre "Girl Of The North Country” is in no way a traditional, it's an original song. But the relationship to the folk ballad "Scarborough Fair" is clearly recognizable and sets his new song in the context of Folk music, a genre that at that time for his listeners had more credibility than the so-called commercial Pop song. But Dylan was never a revivalist, he was and is a popular music songwriter. In this case he was able to make a new song sound old and antique and in that way set it apart from the standard love song of that time. - Authenticity of language Also Dylan's use of language demonstrates his search for a different kind of authenticity. He doesn't try to achieve the refined quality of the best songwriters of the generation before and he obviously didn't want to sound like a professional writer but more like someone who tries to express something without knowing exactly how. This is characteristic for a lot of his early songs ("Tomorrow Is A Long Time" is another striking example). The "antique lyric quality" (Todd Harvey) of "Girl Of The North Country" was somehow outdated at that time, the inversion of adjective and noun in "north country fair" and the second line of verse 4 ("many time I have often prayed" ) would have been regarded as corny and unprofessional by songwriters with a different background. Not at least the rhyme scheme isn't that perfect. Stylistical traits like these have led fundamentalist writers of the older generation like Gene Lees to regard Dylan and the new wave of songwriters as illiterate amateurs. But that misses the point. It was a change in style: the refined language and the artful composition of the lyrics is replaced by a "new authenticity". Credibility, sincerity and naturalness is achieved here by imperfection. Dylan has often been a master in using language, or better: different sets of languages, in his songs - for example antique Folk ballad speech, Blues lyrics, his different amalgams of poetic or quasi-poetic languages and the vernacular - to create an air of authenticity. "Girl Of The North Country" is one of the best early examples for this approach. - Authenticity of performance Important for Dylan was also a new set of performance values that he developed as a contrast and counterpoint to the music of the parents' generation. This older set of values were regarded as inauthentic and untrustworthy by a part of the new generation. Dylan's new "authenticity", derived from Folk, Blues, Rock'n Roll, television and poetry and reflected by his image, his singing style and his music was a result of the generational gap of the 50s and 60s. He surely didn't look and sound like Father Bing and this completely different performance style could even make an old fashioned and rather sentimental love song like "Girl Of The North Country” sound credible again. I think Dylan in fact reanimated and reestablished the love song for a new generation that was extremely skeptical of the older generation's way of writing and singing about love. But it should be noted that he was working on the same basic premises developed since the 20s. Dylan as a singer is still part of the Crosby school in his use of technical means (microphone, the record) to create a sense of intimacy with his listeners, to communicate with them "on a personal basis". His direct role models may have been Guthrie, the "Singing Cowboys” from television like Gene Autry (surely the first "hero with guitar” he encountered in his youth) and maybe Buddy Holly, but he was still walking the same road that had been built by Crosby & Co. His new authenticity in performance and image was in no way a revolutionary change but a set of new clothes for a new generation. - Autobiographical authenticity Though a new kind of personal authenticity was very important for artists at least since the 20s, this romantic concept had much more impact on the audiences since the 60s. A new confessional quality of songs led in extreme to a tendency to regard personal or even autobiographical authenticity as the "hallmark of a 'good' song" (Jeness/Velsey, p. 277). In Dylan's case we are still confronted with endless discussion like: who is the "Girl Of The North Country"? Who is Johanna? He of course often enough alluded to an autobiographical context, not only with songs like "Sara" or "Ballad In Plain D". But at times he obviously seemed to feel plagued by this approach, as in his comment about "You're A Big Girl Now" in 1985: "'You're A Big Girl Now' well, I read this was supposed to be about my wife [...] Stupid and misleading jerks sometimes this interpreters are [...]". Or he joked about it, as in 1975, when he introduced "It Takes A Lot To Laugh” as "an autobiographical song for ya". I don’t know how important biographical interpretations were in the early 60s. But at least since Anthony Scaduto's biography the reception of "Girl Of The North Country" has been dominated by the question if it was Ms H. or maybe Ms. B. For a lot of listeners this shaped a special context for understanding this song: by obviously singing about a real girl the singer shares his personal life with the audience and makes the song more "real", more authentic. But: is "Girl Of The North Country” really about "someone”? Todd Harvey correctly notes that "the lyrics do not, however, contain enough specific information to suggest that Dylan was leaving clues about his personal life". I agree. But in fact this question is not that important! "Girl Of The North Country” is a song, it's in no way autobiography. It's an expertly crafted song - where even possible lingual and stylistic lapses sound appropriate - , drawing from a set of wide-ranging sources and recreating the sentimental, nostalgic love song in a new historical and cultural context for a new audience.

Literature & Links:

Lyrics are quoted from different online resources.

Comments: Please send a mail to info[at]justanothertune.comWritten by Jürgen Kloss

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||