|

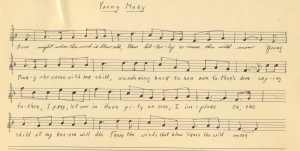

The Adventurous Story Of Poor

"Mary Of The Wild Moor"

I. "One Of Them Old Southern Mountain Ballads..."

"Mary Of The Wild Moor" is a popular song from the 19th century that is known today as an "old Folk ballad".

|

|

|

More Song Histories

|

|

|

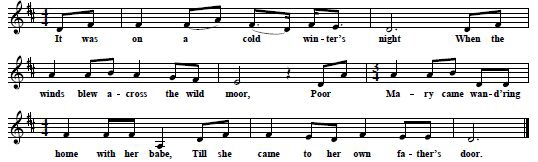

It was first recorded and released by the Blue Sky Boys, - a popular and influential duo from North Carolina - in 1940 for Bluebird (B-8522, see Russell, p. 114; available at YouTube at the moment):'Twas on one cold wint'ry night,

And the wind blew across the wild moor,

When poor Mary came wandering home with her child.

'Till she came to her own father's door.

"Oh Father, dear father" she cried,

"Come down and open the door,

Or the child in my arms it will perish and die,

By the winds that blows across the wild moor.

Oh why did I leave this fair spot,

Where once I was happy and free,

I'm now doomed to roam without friends or a home,

And no one to take pity on me."

But her father was deaf to her cries,

Not a sound of her voice did he hear,

So the watch dog did howl and the village bell tolled,

And the wind blew across the wild moor.

Oh how the old man must have felt,

When he came to the door in the morn,

And found Mary dead but the child still alive,

Closely pressed in its dead mother's arms;

In anguish he tore his gray hair,

While the tears down his cheeks they did pour;

When he saw how that night, she had perished and died

From the winds that blew across the wild moor.

The old man with grief pined away,

And the child to its mother went soon,

And no one, they say, has been there since this day,

And the cottage to ruin has gone;

But the villagers point out the spot,

Where the willow droops over the door,

Saying there Mary died, once a gay village bride,

From the winds that blew across the wild moor.

The allmusic guide lists versions ranging from the classic recording by the Louvin Brothers (1956) to contemporary attempts by David Pajo (2005) and Sara Evans (2001), the latter from the soundtrack to Songcatcher (see IMDB), a movie based very loosely on the life of Folk song collector Dorothy Scarborough. I first heard "Mary Of The Wild Moor" from Bob Dylan who performed it - with Regina Havis singing harmony and playing the autoharp - at 16 shows in 1980 and 1981. It was the time when began to overcome the fervent musical evangelism of his so-called "religious period" and started to reinstate some of his 60s and 70s classics into his concert repertoire. This "old southern mountain ballad" was an ironic answer to the people asking him to play his "old songs" and he used to introduce his fine performances with comments like these:

"All right, we're gonna try something new tonight. Don't know how it's gonna come off, but we'll try it anyway. A lot of people ask me, they want to know about old songs, and new songs and stuff like that. This is a song I used to sing before I even wrote any songs. But this is a real old song, as old as I know. This here is called an autoharp. So this is how I guess you call one of them old folk songs, I used to sing. I used to sing a lot of these things. Well, I hope it brings you back, I know it brings me back. This is Mary And The Wild Moor. I guess it's about 200 years old" (San Francisco, 12.11.1980)

"People are always asking me about old songs and new songs. Anyway, this is a real old song. I used to sing this before I even wrote any songs. One of them old Southern Mountain ballads [...] about somebody dyin' in the snowstorm. Anyway, it's called Mary And The Wild Moor". (San Diego, 26.11.1980)

II. "This Is A Real Old Song..."

"Mary Of The Wild Moor" is in fact an "old" song, but not as old as other so-called "folk songs". The text first appeared on broadside sheets in England in the early 19th century. By all accounts it was a very popular broadside ballad. At least 36 printers not only from London but from all over Britain have published the song. Besides these we also have some more - at least 10 - without imprint and in these cases it is impossible to say where or when they were printed. These numbers are based on the extant copies available in the two massive collections, the Bodleian Libraries' Broadside Ballads Online (BBO) and the Madden Ballads (MB) as well as the references in the Roud Index (No. 155). There is no doubt that there have been more. What has survived is surely only a part of what was printed at that time.

It is important to distinguish between two kinds of popular songs common at that time. First there were those written and produced for the more educated people. They were usually performed by the great singing stars of that era and published as sheet music as well as in more expensive song books. The target group were those who could afford these publications and were able to read music. Typical examples are hits like "Robin Adair" - introduced by the great John Braham in 1811 - and the works of composers John Whitaker and Joseph Augustine Wade, to name only two of the successful songwriters of this era.

Then there were the broadside ballads, cheaply produced and cheaply sold, the "literature of the poor people" (Shepard 1969, p. 14). The friends of more sophisticated music used to look down on these kind of songs. The editor of a Book of Modern Songs (London 1858, p. iii) complained about "those questionable productions [...] popular enough in the streets and at the lower-class theatres and concert-rooms". Of course the texts of many of the most popular hits were also reprinted - illegally and unauthorized - by the broadside publishers. The poor people also loved Braham & co. and they also knew these kind of songs and their tunes. But this was a one-way street. Only very few of those songs originating as broadsides were promoted to higher class popular music. In England "Mary Of The Wild Moor" was not among them. It was never published as sheet music and it never appeared in any of the popular song collections like Bingley's Select Vocalist (1842, available at the Internet Archive) or Davidson's Universal Melodist (1853, available at the Internet Archive). This song remained p art of the "lower" stratum of popular music.

When was this song first published? This question is not easy to answer. The printers never included the year of publication on these sheets, they were not registered for copyright and of course they were never announced or reviewed in newspapers and magazines. In fact I know of no single reference to this song in contemporary publications. In the library catalogs and the broadside collections we only find very rough and imprecise datings that usually reflect the business years of the respective printers.

It is a good idea to start with the two most important British broadside publishers of the first half of the 19th century, John Pitts and James Catnach. Both have published this song in several editions and it looks as if these are among the earliest of the surviving prints. Pitts and Catnach, very successful businessmen in Seven Dials - "the largest and most squalid slum in London" (Shepard 1969, p. 39) - dominated the broadside market during this era. According to an article about "Street Ballads" in the National Review in 1861 (p. 400) even Catnach's successors still had "on stock half a million of ballads, more than 900 reams of them". They both supplied pedlars, hawkers and patterers with broadsides that these middlemen sold not only in London but all over England (see f. ex. Shepard 1973, pp. 99-101; Shepard 1969, pp. 45-6). Not at least they also furnished provincial printers with material. For example Joseph Russell in Birmingham - he was busy between 1814 and 1839 - made a "'little fortune' by 'printing and selling Catnach songs'" (quoted by Palmer, Birmingham Ballad Printers 3, available at mustrad.org).

John Pitts started his business in 1802 at No. 14, Great St.Andrews Street. In 1819 he moved to No. 6. Three extant prints can be found in the Bodleian’s collections (Harding B 25(1538), Harding B 11(2789), Harding B 17(243b), here at Broadside Ballads Online) and one in Madden Ballads (MB 04-2908). The imprint on these four editions is "Pitts, Printer, Wholesale Toy and Marble Warehouse, 6, Great St. Andrew-street, Seven Dials". This means that they were all published since 1819. There is no evidence that he had printed this song at his first address.

Most interesting is one print, Harding B 25(1538) (BBO). This is the only one of all extant British versions of this text where a tune - "Robin's Petition" - is indicated. That melody was composed by John Whitaker and published in 1814. I will discuss this song later but at least it should be noted that it was not uncommon for the broadside printers to borrow the tunes of popular hits for new pieces. A single sheet with a slightly different text (Harding B 17(243b), BBO) doesn't name the tune but it is simply impossible to know which one was published earlier. Nor is there any external evidence that would help to determine more exact publication dates.

On another sheet (Harding B 11(2789), BBO) "Poor Mary Of The Moor" was combined with a song called "Old England For Ever Shall Weather The Storm" as well as a parody of that piece. The tune of "Old England" was written by composer Thomas E. Williams (d. 1854, see Brown/Stratton 1897, p. 449 & Grattan Flood 1915). By all accounts this popular patriotic song was a product of the 1820s. We find it for example in Vol. 3 of the Universal Songster (1826, p. 251, at Google Books). Pitts only published the text from his new address (MB 04-2908). The earliest available broadside seems to be one by Catnach (reprinted in Goldstein 1964, p. 56, at Google Books). Thankfully we can read on this sheet that it was also "sold by [...] Hook, Brighton". Richard Hook was apparently only busy during the first half of the 1820s (see British Book Trade Index and also Hepburn 2000, p. 201). But of course this is in no way conclusive evidence for a definitive publication date of "Poor Mary Of The Moor". The only thing we know at this point is that Pitts' sheet with "Poor Mary" and "Old England" can't have been published before 1820. But on the other hand it is not unreasonable to assume that both songs belong to the same time period, the early 20s.

Some more information can be derived from the broadsides published by James Catnach, Pitts' great rival (see Hindley 1878, a fascinating biography, available at the Internet Archive). He started his business in 1813 at 2, Monmouth Court and remained there until he retired in 1838 (see Shepard 1969, pp. 46 & 74). Therefore his publications are usually dated in catalogs as from "1813-1838". That's of course not very helpful. But thankfully Catnach's catalog from 1832 has survived and here this song is listed. He called it "Mary Of The Moor" (MB 05-1832, p. 4; also reprinted in Shepard 1973, pp. 216-23, here p. 219). At least we know now that it was available before that year. This is confirmed by another edition by London printer T. Batchelor, "14 Hackney Road, Crescent", one of Catnach's "agents" who was busy between 1828 and 1832 (see Madden Ballads, Publisher's Introduction).

Catnach also combined "Mary" with other pieces. There is one sheet where it is printed together with "The Waterman" (see Copac) and another one with not only "The Waterman" but also "All's Well" (see Copac). These are both older songs. "All's Well" was written by John Braham and Thomas Dibdin and first published around 1803 (see Copac) while "The Waterman" was known at least since the 1810s. Pitts had printed this song both at his first address before 1819 and at his new location after that year (see MB 03-2323 & 04-2791). But there is no evidence that "Mary" is as old as these two pieces. It was not uncommon to print new songs with popular oldies and these two sheets look like a typical example for this practice.

Much more helpful is a so-called "Long song-sheet" with the title St. James's Looking Glass that is available in two versions. These kind of collections of songs on a big sheet of paper tha t were sold very cheaply on the streets were an innovation either by Catnach or Pitts (see Shepard 1963, p. 81; Shepard 1969, p. 55): t were sold very cheaply on the streets were an innovation either by Catnach or Pitts (see Shepard 1963, p. 81; Shepard 1969, p. 55):

"The long-song sellers did depend on the veritable cheapness and novel form in which they vended popular songs, printed on paper, three songs abreast, and the paper was about a yard long, which constituted the three yards of song. Sometimes three slips were pasted together. The vendors paraded the streets with their three yards of new and popular songs for a penny. The songs are, or were, generally fixed to the top of a long pole, and the vendor cried the different titles as he went along". (Henry Mayhew, London Labour And The London Poor, Vol. 1, 1861, p. 221)

One version of this "Long song-sheet" has 12 songs ((Harding B36(15), not available online at the moment; also MB 05-3556) and one only nine texts (Johnson Ballads, fol. 27, BBO). Nearly all of the songs printed here besides "Mary Of The Moor" can be found in Catnach's 1832 catalog. Most of them seem to be from the 20s but some are a little bit older. Thomas Campbell's "Poor Dog Tray" and "The Mariners Of England" were written at the turn of the century and "Robin Hood" was first published in 1751 as part of a "New Musical Entertainment" about this famous outlaw (ESTC T212637, available at ECCO). In fact this is a typical compilation of old hits and new songs, both broadside ballads and works by popular poets. I have no idea why this sheet was called "St. James's Looking Glass". Perhaps this was a performance venue or maybe an attempt at a periodical. There was another one with that title, also printed by Catnach, that includes a "series of cuts, followed by a song and monologue written by David Roach, all satirizing various personalities of the time" (see Copac).

In the catalog of the British Library these broadsides are dated as from "1829?" (see Copac). This is not an unreasonable assumption. On the shorter version with nine songs we can find the note that it was also "Sold by Simmons [sic!], Reading". According to the British Book Trade Index John Simons in Reading was busy between 1826 and 1830. In fact this is the earliest reasonably dateable print of "Mary Of The Moor" and we can at least safely assume that this song was already available in the second half of the 1820s. But it can't have been the first published version. We can find "Poor Mary Of The Moor" listed in one catalog from the first half of the 1820s. Richard Hook from Brighton sold a broadside with this text (see Roud Index S158250, MB 11-7526) and - as already mentioned - he apparently was busy only between 1820 and 1824. This is the earliest datable reference to the song. But it is very unlikely that Hook was the one who had published it first. Some more of of his broadsides can be found in the Madden Ballads (MB 11-7511 - 7526). An considerable part of these are standards from that era that were also sold by Catnach and Pitts. It is not unreasonable to assume that he had also received "Mary" from one of the London publishers. Mr. Hook had business connections with James Catnach (see Hindley 1878, p. 90) but in this case Pitts may have been his supplier. His text had the same title as the latter's version: "Poor Mary Of The Moor".

But of course this is more speculation than proof and here we can see how scarce the documentation is. Hook's broadside with this song hasn't survived and we only know of it because it is listed in his catalog. Otherwise there is no further conclusive evidence that "Mary" was already available in the early 1820s. This in in fact the only thing we know at the moment. It is not possible to find out which printer had been the first to publish this text on a broadside. Even if Hook had used Pitts' version it doesn't exclude the possibility that Catnach was the song's originator. There was a "powerful rivalry" (Hindley, p. 49) between these two businessmen and they always took great pains to outdo each other. According to Hindley (p. 49) "each printer accused the other of obtaining an early sold copy, and then reprinting it with the utmost speed, and which was in reality often the case, as 'Both Houses' had emissaries on the constant look-out for any new production suitable for street-sale".

The text of "(Poor) Mary Of The (Wild) Moor" on the British broadsides remained very stable. The words used by Catnach on all of his broadsides and by Pitts on all except one were reprinted by most of the other publishers:

'Twas one cold night when the wind

It blew bitter across the wild moor,

When poor Mary she came with her child,

Wandering home to her own fathers's door,

She cry'd, father, oh pray let me in,

Do come down and open your door,

Or the child at my bosom will die,

With the wind that blows 'cross the wild moor.

Why did I ever leave this dear cot,

Where once I was happy and free,

Doom'd now to roam without friend or home,

Oh, dear father, take pity on me.

But her father was deaf to her cries.

Not a voice, not a sound reach'd the door,

But the watch-dog's bark, and the wind

That blew loudly 'cross the wild Moor.

But now think what the father he felt,

When he came to the door in the morn,

And found Mary dead, the child still alive,

Fondly clasped in its dead mother's arms.

Wild and frantic he tore his grey hairs,

As on his Mary he gaz'd at the door,

'Who in the cold night had perish'd and died

With the wind that blew 'cross the wild Moor.

Now the father in grief pined away,

The poor child to its mother went soon,

And no one they say has liv'd there 'till this day,

And the cottage to ruin is gone.

And villagers point out his cot,

Where a willow droops over the door,

Cries there Mary died once our village pride,

With the wind that blew 'cross the wild Moor.

One of Pitts' editions, the one where "The Robin's Petition" is named as the tune (Harding B 25(1538), BBO) offers some minor variations. The first line reads "'Twas one cold winter night [...]" instead of "'Twas one cold night when [...]" and in verse 2 it is a "fair cot" instead of a "dear cot". This text was reprinted occasionally by other publishers (see f. ex. Harding B 11(4232), by J. Harkness, Preston, between 1840 and 1866, BBO). But these are really no earth-shattering changes.

The original melody of "Mary Of The Wild Moor" is not definitely known but there is good r eason to assume that it was in fact "The Robin's Petition". That song was one of the great popular hits of this era. The words were originally a children's poem from Maria Edgeworth's Continuation of Early Lessons (1814). It is part of the story "The Bee And The Cow" from her series of tales about "Rosamond" (here in a complete edition of the Early Lessons [18??], p. 139/40). But the poem itself is possibly older. A version with some more verses had already been published in 1802 in the Scots Magazine (p. 921). eason to assume that it was in fact "The Robin's Petition". That song was one of the great popular hits of this era. The words were originally a children's poem from Maria Edgeworth's Continuation of Early Lessons (1814). It is part of the story "The Bee And The Cow" from her series of tales about "Rosamond" (here in a complete edition of the Early Lessons [18??], p. 139/40). But the poem itself is possibly older. A version with some more verses had already been published in 1802 in the Scots Magazine (p. 921).

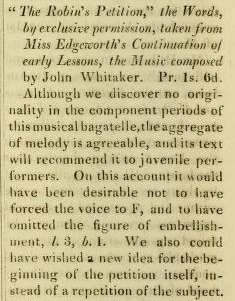

In 1814 John Whitaker added a melody and published it as a song. Whitaker (1776-1848; see Brown/Stratton 1897, pp. 443-4) was a very popular composer of that time and also one of the owners of the music publishing firm Button & Whitaker in London (Kidson 1900, p. 21). He was involved in the writing of Guy Mannering, a very successful opera (1816, with Henry R. Bishop) and also composed the tunes for songs like "My Poor Dog Tray" (words by Thomas Campbell), "Emigrant's Farewell" (see Copac), "Indian Maid" (see Copac), "Oh Rest Thee Babe" (see Copac) and "Mary's Love" (see Copac). Apparently the quality of his melodies was especially noteworthy. For example an ad in The Harmonicon. A Journal of Music in December 1824 (p. 270) pointed out the "sweet fancy and poetic elegance" of his compositions:

"Their simplicity recommend them to the lovers of melody, and their graceful arrangements will ensure them a good reception with the scientific".

The reviews of  "The Robin's Petition" were mostly positive. The British Lady's Magazine & Monthly Miscellany (Vol. 2, No. 11, November 1815, p. 334) noted that this "little ballad is remarkable for its simplicity and neatness". The Monthly Magazine And British Register (Vol. 39, No. 265, February 1815, p. 61) called it "one of the pleasing novelties of the day" and 10 months later the same publication (Vol. 40, No. 276, December 1815, p. 451) recommended this song once again: "The Robin's Petition" were mostly positive. The British Lady's Magazine & Monthly Miscellany (Vol. 2, No. 11, November 1815, p. 334) noted that this "little ballad is remarkable for its simplicity and neatness". The Monthly Magazine And British Register (Vol. 39, No. 265, February 1815, p. 61) called it "one of the pleasing novelties of the day" and 10 months later the same publication (Vol. 40, No. 276, December 1815, p. 451) recommended this song once again:

"The melody of this little ballad is natural, appropriate, and attractive. We do not mean to say, that there is much in it; but that the little it possesses is good. With the introductory and concluding symphonies, we are much pleased"

A second edition of "The Robin's Petition" was published by Whitaker & Co. in 1819 and the song was regularly reprinted (see Copac) during the next decades. An American version in a collection for children called Little Songs For Little Singers (New York 1854, at Music For The Nation, LOC) had a different melody and was credited to one Max Braun.

"The Robin's Petition" must have been very popular in Britain. I found 23 broadsides in the Bodleian's collections (see Broadside Ballads Online). On Catnach's Windsor Songster (Harding B35(18), between 1813 and 1838) it's called a "favourite song". It was also included in song collections like The Universal Songster, or: The Museum of Mirth (London 1834, p. 43/44)) and in Davidson's Universal Melodist (London 1854, p. 276), here with melody:

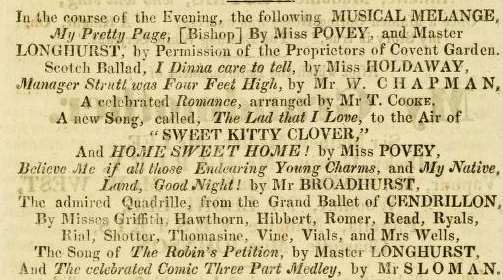

The song was also performed on stage and is for example listed on a playbill for the Royal English Opera House in London from 1823. The people used to sing it, too. Reader W. W. Strugnell reported in Notes &  Queries in December 1875 (Ser. 5, Vol. 4, p. 504) that "The Robin's Petition" "is sung at the door of every house" in Cheltenham "at Christmas-tide". Queries in December 1875 (Ser. 5, Vol. 4, p. 504) that "The Robin's Petition" "is sung at the door of every house" in Cheltenham "at Christmas-tide".

The lyrics of this song are thematically related to "Mary Of The Moor". It is about a robin searching for shelter from the cold winter and a couple of ideas obviously have found their way into the lyrics of "Mary". Besides that it is no problem to sing the words of "Mary Of The Moor" to this tune.

III. Broadsides And Popular Songs

At this point we only know that the words of "Mary Of The (Wild) Moor" were most likely first published on broadsides during the first half of the 1820 and that the original melody was apparently borrowed from a popular hit written by composer John Whitaker. That's not much and in fact there is much more we don't know than what we know. A lot of questions remain: who has written this text and who has performed the song?

There was a wealth of professional public entertainment in 19th century London: from the poor or not so poor street singer to theaters like the Adelphi, from the pub houses to the pleasure gardens. The theater wasn't yet an exclusive domain of the higher and more educated classes. Performers of the highest ranks like Luzia Vestris, John Braham, John Liston or Maria Theresa Bland were popular among all Londoners and they used to perform all kinds of songs. The major function of broadside song sheets was to offer the lyrics of those songs popular at the moment to the prospective customers who had heard these songs in performance. "Three yards a penny! Three yards a penny! Beautiful songs! Newest songs! Popular Songs! Three yards a penny! Song, song, songs!" (Mayhew 1861, p. 221) the sellers used to shout to advertise their long song sheets.

The terms "broadside ballad" or "street literature" are a little misleading. They are surely appropriate for the topical broadsides, the "Ballads on a Subject" like the gallows literature that was the very lucrative main business of printers like Catnach. These "murder sheets" (see Shepard 1962, p. 80) were sold in great amounts, some of them even in a million copies. But songs on broadsides usually didn't originate on the streets but from professional entertainment. "[...] whatever was popular singing material was also very soon appropriated and sold on the streets" (Joy, p. 9).

This was in no way a new phenomena of the 19th century. Already "in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries [...] many [songs that were later called 'Folk Songs'] came from professional entertainers and writers for special occasions". And it should not be forgotten that Samuel Pepys in 1666 heard 'Barbara Allen's Cruelty from a stage actress, his beloved Mrs. Knipp, "and it may have made its debut on that occasion" (Pound, Nebraska Folklore, pp. 236/7). Since the late 18th century with "the institution of Pleasure Gardens, like Vauxhall, Marylebone and Ranelagh, where music was a regular attraction" street broadsides show an "increased preoccupation with professional performers and shows" (Shepard 1962, pp. 71/73).

Now printers like Catnach and Pitts were busy bringing "all the standard and popular works of the day [...] within the reach of all" (Brown, quoted from Hindley 1886, p. 222). In the 1840s Henry Mayhew (p. 280) was told that "all those sort of songs come now to the streets [...] from the concert rooms". For the printers it was an easy job. They could simply "steal" the songs and sell them cheaply on the streets. "They come to the printer, for nothing, from the concert-room" (Mayhew, p. 278) or they could be copied from popular songbooks by the major song publishers. Catnach published "all sorts of songs and ballads, for he had a most catholic taste, and introduced the custom of taking, from any writer living or dead, what ever he fancied, and printing it side by side with the productions of his own clients" (Anon., Street Ballads, 1861, pp. 415-6).

"Long song-sheets" from the this time period offer interesting collections of popular songs that were sometimes dedicated to a performer or a venue. Titles of these broadsides as found in the Bodleian's collections were for example: The Rural Songster; Liston's Drolleries; The Vocal Braham; The Musical Museum. A collection of excellent songs or the Vauxhall Songster (at BBO). Performers were mentioned not that often, only if they were very popular "stars" like Braham, Liston, Mme. Vestris, Ms. Bland or Catherine Stephens. Their names surely helped selling the song sheets.

But unfortunately there is no evidence that "Mary" was ever performed by one of these or other notable singers of that era. In fact it is not known who sang this song. By all accounts it was - to quote again the editor of the Book of Modern Songs (Carpenter 1858, p. iii) - one of "those questionable productions [...] popular enough in the streets and at the lower-class theatres and concert-rooms" and the names of the performers are forever lost.

The writer of "Mary Of The Moor" has also remained anonymous, he wasn't credited. But that was standard practice of all printers and happened even to songwriters of the higher ranks like Joseph A. Wade. His "Meet Me By The Moonlight Alone" (1826) was among the most popular songs of the 19th century and widely reprinted on broadsides in Britain. This song can also be found on "Long song-sheets" from the 20s like Catnach's Life In London Songster (Harding B 36(9)) and Pitts' The Harvest Concert ( Johnson Ballad fol. 121) but his name is never mentioned. Usually only well known poets and writers dead or alive like Burns, Clare, Campbell - responsible for two songs on The St. James's Looking Glass -, White or John Howard Payne, the author of the great hit "Home Sweet Home", were credited. But that may have helped more selling the broadsides than supporting the poets themselves or their heirs who surely weren't paid anything.

So for the most part of the 19th century we don't know who actually wrote the songs. Occasionally it may have been the performers and musicians themselves. But often enough the singers and concert halls as well as the broadside printers bought the lyrics from the street and tavern poets. But at least some information about these writers is available.

In a book called Real Life In London (Egan 1821, pp. 512-3, at Gutenberg.org; also in Hindley 1878, pp. 176-7) we can find an interesting report about one Mr. Goosequill, an up-and-coming playwright who had some problems selling his theatrical works. But he had "made an agreement with a printer of ballads in Seven Dials, who, finding his inclinations led to poetry, expressed his satisfaction, telling him that one of his poets had lost his senses, and was confined to Bedlam, and another was dazed with drinking drams". This work brought him some income but not much. He only "earned five-pence-three-farthings per week".

Pitts and Catnach had a "stuff of bards" (Hindley, p. 49) and the latter "was a bit of the poet" (Hindley, pp. 156-7) and even wrote new song lyrics himself. The author of an article about "Street Ballads" in the National Review (1861, pp.415-6) reports that he had often heard that Mr. Catnach "kept a fiddler day and night in a backroom, where he used to sit, like Old King Cole, with a pot of ale and a long clay, receiving ballad-writers and singers, and judging of the merits of any production which was brought to him by having it sung then and there to some popular air played by his fiddler" (pp. 415-6). Hindley (p. 157) gives an interesting description of a typical songwriting session:

One of his friends "had a fine voice [and] used to sing the tune over while Jemmy composed. Many a ballad was thus produced: the elaboration of the ideas, the length of the lines, and the setting of the type all going on simultaneously, 'Sing it over again, Tom,' was a frequent request, and when the verse and music did not satisfy Jemmy's ear, and after repeated efforts, it was pronounced fit for the national taste, and then printed off for immediate sale".

Later Hen ry Mayhew (p. 279f) was even able to interview one of these poets who had to work on both sides of the tracks to make a living, for the printers and for the concert-venues and whose songs had been very successful. They can be found in the broadside archives and some of them were even published in the USA: : ry Mayhew (p. 279f) was even able to interview one of these poets who had to work on both sides of the tracks to make a living, for the printers and for the concert-venues and whose songs had been very successful. They can be found in the broadside archives and some of them were even published in the USA: :

"The first song I ever sold was to a concert-room manager. The next I sold had great success. It was called the `Demon of the Sea,' and was to the tune of `The Brave Old Oak.' [...] That song was written for a concert-room, but it was soon in the streets, and ran a whole winter. I got only 1s. for it. Then I wrote the `Pirate of the Isles,' [New York ca. 1860s] and other ballads of that sort. The concert-rooms pay no better than the printers for the streets. Perhaps the best thing I ever wrote was the 'Husband's Dream.' [New York ca 1860] [...] I dare say I've written a thousand in my time, and most of them were printed. I believe 10,000 were sold of the `Husband's Dream.' [...]"

It seems that songwriter wasn't a well-respected job at that time nor was it a profession to get rich with. These anonymous street poets surely were educated and very experienced professionals but of course they were never reviewed in the British Ladies Magazine or in the Monthly Magazine And British Register.

IV. Sad Tales Of Betrayed Mothers And Poor Orphans

"Mary Of The Moor" treats a topic well known from literature and song: the girl with child - sometimes illegitimate - is betrayed and left by her husband or lover, she wants to return home but her father despises her and in the end she and the child will die. German readers may be aware for example of Gottfried August Bürger's Des Pfarrers Tochter von Taubenhain (1778), where this topic is combined with that of the desperate mother murdering the child.

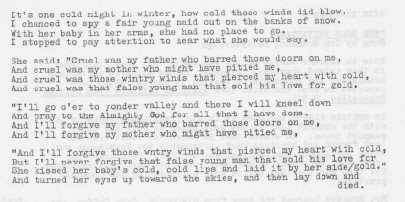

But it isn't necessary to go that far, British songs from the broadside collections offers enough possible precursors and parallels. There is for example a ballad called "Winter's Evening, or: The deploring damsel", printed in London between 1780 and 1812 (Harding B 17 (342a), BBO), also in Newcastle between 1774 and 1825 as "The Winter's Night" (Harding B 25(2058),BBO), and then reprinted in Britain at least until the 1850s. In the 20th century it was collected by Folklorists in Britain, Ireland, Canada and the USA as "The Fatal Snowstorm" or "The Forsaken Mother And Child" (Roud # 175):

Twas one winter's evening when first came down the snow,

And bleak o'er the wild heath a bitter blast did blow.

I saw a damsel all alone and weeping on the way

She p[r]est her baby to her breast, and sadly then did say -

How cruel was my father to shut the door on me,

And cruel was my mother such a sight to see;

How cruel is the winter wind that chill my heart with cold,

How cruel also then was he that left his love for gold.

Hush, hush my dearest baby, I'll warm you at my breast,

How little does your father think how sadly we're distrest;

As wretched as he is, did he but know how we fare,

He'd shield us in his arms, from the bitter piercing air.

Hush, hush, my little baby, thy little life's gone."

Let these tears revive you that trickle fast down,

So fast the tears flow they as they fall.

O wretched, wretched mother, was our downfall.

Down she sun despairing on the drifted snow,

And filled with anguish, lamenting her woe;

She kiss'd her baby's lips, & laid it by her side,

She cast her eyes to heav'n, bow'd her head and died.

This song alone could easily have served as a model and inspiration for the writer of the lyrics of "Mary Of The Moor". It is surely one of the saddest songs I've ever seen and it has an obvious theatrical quality. I can actually imagine it performed by an actress on stage. But there is one major difference in motives: this song has the cruel father who had "shut the door" on the girl while in "Mary" he was only "deaf to her cries" because he wasn't able to hear her voice: the wind "blew loudly 'cross the wild moor". The different dramaturgy allows the sorrowful father's death at the end of the song and makes the whole story even more tragic than "Winter's Evening".

The other major difference is that "Mary" lacks most of the background of the girl's story. It is never explained - as in "Winter's Evening" - why she returns home with her child in a dark and stormy night, except for a short allusion at the end that she once had been "our village pride". Maybe the song was originally only a part of a stage play that had offered Mary's story, or maybe it had been introduced with a narrative describing the background.

But the listeners and readers of that era surely didn't have any problems understanding this ballad. There were enough songs around that offered versions of this very popular topic. One example from the same is "Wandering Girl", here from a London broadside dated 1817 - 1828 (Firth c. 18(104), BBO), also reprinted in later years. Here the girl with her child, left by her true love and despised by her father, "must wander like one that is poor". The grim ending is missing, instead she warns all "pretty fair maids [...] never trust a young man in any degree":

I lov'd a young man as dear as my life,

He often told me he'd make me his wife,

But now to some other fair girl he is gone,

Left me and my baby in sorrow to mourn.

Chorus:

My truelove has left me I know not why,

Left me and my baby in sorrow to cry,

My father and mother forget I ne'er shall,

How they've turned their backs on the Wandering Girl.

My father despises me because I did so,

Now I'm despis'd by the girls that I know,

My father and mother turn'd me from the door,

Now I must wander like one that is poor.

Once I was fair as the bud of the rose,

Now I'm pale as the lily that grows,

Like a flower in the garden my beauty is gone,

See what I come to by loving a man.

Come ye pretty fair maids wherever ye be,

Never trust a young man in any degree,

They'll kiss you, and court you, and swear they'll be true,

And the very next moment they'll bid you adieu.

Another Mary's story is told in "Blue-Eyed Mary Or: The Victim Of Seduction" (Harding B 11(346), BBO), also printed by Catnach, but not dateable, so it may also postdate "Mary Of The Moor". This girl from a "cottage embosom'd within a deep shade", at first also the pride of the village, is seduced by a squire, follows him to the town and in the end dies as a prostitute:

In a cottage embosom'd within a deep shade,

Like a rose in the desert ah, view the meek maid,

Her aspect a' sweetness, al plaintive her eye,

And a bosom for which e'en a monarch might sigh.

Then in neat Sunday gown see her met by the squire,

All attraction her countenance, his all desire:

He accosts her by blushes - he flatters, she smiles -

And soon Blue-Ey'd Mary's seduced by his wiles.

[...]

Now with eyes dim & languid, the once blooming maid,

In a garret on straw faint and helpless is laid;

Oh! mark her pale cheeks,she scarce draws her last breath,

And lo! her blue eyes are now sealed up in death.

Even printer James Catnach himself tried his hand at a song about this extremely popular topic. His "Home", first published in 1823 in The May-flower. New songs (Johnson Ballads fol. 17), was written to the melody of "Sweet Home" by John Howard Payne, one of the great hits of that time and is a good example for a typical answer-song. Later it was even printed by Catnach's rival Pitts side by side with the original and another parody (Harding B 11(3711), BBO) :

I was courted by a young man who did me betray,

From the cot of my childhood he led me away;

But now he has left me in sorrow to roam,

Far, far from my parents, and far from my home.

Home! home! sweet, sweet home!

There's no place like home.

[...]

Farewell, peaceful cottage, farewell happy home,

For ever I'm doom'd a poor exile to roam;

But this poor aching heart must be laid in the tomb,

Ere it can forget the endearments of home. -Home! home! &c

Wandering girls were usually betrayed mothers with a little child, the wandering boys used to be poor orphans. A well known example is Henry Kirke White's (1785 - 1806) poem "The Wandering Boy" where the "winter wind whistles along the wild moor". It circulated widely on broadsides and was performed by singers. Liston's Drolleries (Catnach 1822, Johnson Ballads fol. 14, BBO) includes the original version as "sung by Master Hyde at the London concerts":

When the winter wind whistles along the wild moor,

And the cottager shuts on the beggar his door;

When the chilling tear stands in my comfortless eye,

Oh, how hard is the lot of the Wandering Boy.

The winter is cold, and I have no vest,

And my heart it is cold as it beats in my breast;

No father, no mother, no kindred have I,

For I am a parentless Wandering Boy.

Yet I had a home, and I once had a sire,

A mother who granted each infant desire;

Our cottage it stood in a wood-embower'd vale,

Where the ringdove would warble its sorrowful tale.

But my father and mother were summoned away,

And they left me to hard-hearted strangers a prey;

I fled from their rigour with many a sigh,

And now I'm a poor little Wandering Boy.

The wind it is keen, and the snow loads the gale,

And no one will list to my innocent tale;

I'll go to the grave where my parents both lie,

And death shall befriend the poor Wandering Boy.

But there were also versions circulating with two additional verses at the end that hadn't been part of White's original (Johnson Ballads 2961, ca. 1824):

I'll lay my self down I'm denumbed with could [sic!],

My cry is no hard [sic!] by the yound [sic!] nor the old,

All the days of my life have been clouded from joy,

There's nether friends nor a home for the wandering boy.

The door which he lay at belonged to a squire,

Whose house might have sheltered his limbs by the fire,

But when the door open'd they beheld with their eyes,

Lying lifeless and pale, the poor wandering boy.

Here the poor boy is suffering the same fate as Mary and is found dead the next morning. Another related song is "The Soldier's Boy" (Roud # 258) that describes a similar scene (Catnach, ca. 1828/29?, Harding B 17(291a) and more often):

The snow was fast descending,

and loud the wind did roar,

When a little boy friendless,

came up to a Lady's door.

as the Lady sat at the window,

He raised his eyes with joy,

Lady gay, take pity pray,

Cried the poor soldier's boy.

[...]

Now the snow is fast descending

and night is coming on,

Unless you are befriending,

I'll perish before morn.

Then how it will grieve your heart,

And your peace of mind destroy,

To find me dead at your door in the morn.

The poor Soldier's Boy

But in this case the poor boy is saved:

The lady rushed from her window,

and opened her mansion door,

Come in she cried misfortune's child

You shall never wander more.

For my only son in battle fel

Who was my only joy.

And while I live I'll shelter give to a poor

Soldier's Boy.

A similar story about an orphan wandering through the "dreary moor", also with a positive ending, can be found in The "Farmer's Boy" (Roud # 408), a song printed by Catnach in some of his Long song-sheets like Cupid's Bower and The Jessamine and reprinted throughout the century, here quoted from Harding B 11(1152):

The sun went down beyond your hill

Across your dreary moor,

Wary and lame, a boy there came,

Up to a farmer's door

[...]

One favour I have to ask

Will shelter me till break of day,

From this cold winter's blast

Another song touching this topic is "Poor Little Sailor Boy", also very popular at that time (for example with "Poor Mary Of The Moor" on Harding B 17 (243b) by Pitts). "The Robin's Petition", the song that may have furnished "Mary" with its melody may have been an inspiration too, it belongs to the same family (Johnson Ballads 260, all BBO).

"Mary Of The Moor" is for the most part a combination of motives and ideas from songs about the "wandering girl" and the "wandering boy". Nearly all elements of "Mary" can be found in the lyrics quoted and the writer surely was aware of them. Even songs with different topics may have offered some inspiration. The St. James's Looking Glass also includes "The Blue-Eyed Stranger" - the first print of this one is from the early 20s (Harding B28 (58)) - that opens with a similar scenery and also uses the image of the father with "frantic" hair gazing upon a girl:

One night the north wind loud did blow,

The rain was fast descending,

The bitter of heartfelt woe,

The darken'd sky was rending

[...]

My father stood with frantic air [sic!],

And gazed upon the maiden,

Whose heart was broke in sad despair,

And mind with sorrow laden

The author of "Mary Of The Moor" only needed to grab into the big bag of motives available at that time to create another song about a topic popular at that time.

V. How To Write An "Old" Song

Though most likely derived from contemporary popular songs the style is different. The lyrics read like a pastiche of older ballads like "Barbara Allen" with some additional melodramatic effects. "Mary" has all ingredients of a "fabricated Folk-Song". This is not meant as a pejorative value judgment but as a description of style. The language sounds stilted and is approaching fairy-tale style, the rural scenery is stylized and artificial like a setting on a stage. The melody used by the writer had originally been created for a children's poem, "The Robin's Petition". The narrative is constructed like an historical legend, opening with the classic introductory formula:

and ending with the villagers pointing out the old cottage that "to ruin" has gone:

Only the willow "over the door" remains as a memento of that drama and indicates the place where Mary had died.

Maybe the writer had "Barbara Allen" - a song still or again very popular at that time - in mind when he conceived "Mary Of the Moor". Both songs share the tragic ending with the father "pining away in grief" after finding Mary in the morning just like Barbara Allen died of sorrow after her young man's death. Also the refrain lines are constructed similarly and the real culprits, Barbara Allen respectively the "winds that blew 'cross the wild moor", are placed at the end of the verses. Comparing these two songs makes me wonder if "Mary" was originally intended as some kind of parody of an "old" Folk ballad.

It should be noted that it was - in the context of European romanticism - the time of the very first "Folk Revival", the blueprint for all later revivals. Since the 18th century urban intellectuals in Europe had "turned their attention as never before to the vernacular culture of their country's peasants, farmers and craftspeople [...] Once scorned as ignorant and illiterate, ordinary people began to be glorified as the creators of cultural expression with a richness and depth lacking in elite creations" (Filene, p. 9). The fascination with the "Folk" and with a rural past more imagined than real was in Britain as important as in all other European countries and a lot of writers - from antiquarians to poets - were busy researching and recreating ballads and songs from the olden times.

These ideas have tremendous reverberations until today. There is first and foremost the fascination with anything that's "old", especially if it seems to have rural origins. The search for "authenticity" also "implies the existence of its opposite, the fake [...] identifying some cultural expressions or artifacts as authentic, genuine, trustworthy, or legitimate simultaneously implies that other manifestations are fake, spurious, and even illegitimate" (Bendix, p. 9). Since that time we also have a class of mostly urban intellectuals that claims to know much better than the "Folk" how to define this term and what is supposed to be "old" and "authentic". A didactic element has also been a part of this ideology: the desire to refresh and revitalize the whole culture or at least one's own work with the help of the products of the authentic "Folk". And not at least the idea of creating the "old" anew started in this era with the heavy-handed editing of sources by antiquarians and folklorists and with poets writing in the "old" style. These ideas have tremendous reverberations until today. There is first and foremost the fascination with anything that's "old", especially if it seems to have rural origins. The search for "authenticity" also "implies the existence of its opposite, the fake [...] identifying some cultural expressions or artifacts as authentic, genuine, trustworthy, or legitimate simultaneously implies that other manifestations are fake, spurious, and even illegitimate" (Bendix, p. 9). Since that time we also have a class of mostly urban intellectuals that claims to know much better than the "Folk" how to define this term and what is supposed to be "old" and "authentic". A didactic element has also been a part of this ideology: the desire to refresh and revitalize the whole culture or at least one's own work with the help of the products of the authentic "Folk". And not at least the idea of creating the "old" anew started in this era with the heavy-handed editing of sources by antiquarians and folklorists and with poets writing in the "old" style.

The idea of the special value of something that is "old" and of rural origin quickly found its way to the common folks, both the "Folk" on the countryside and the "rabble on the streets" in the towns, the latter watched by ideologists with suspicion and disgust. Old and new "old" songs were part of the popular music scene of that day. For example Allan Ramsay's songs had been "warbled, to raptorous applause, by the favourite vocalists at the London 'gardens', and other places of popular resort. Familiar with the old popular songs of both countries [England and Scotland] he utilized them for his own purposes [...] His manner was exactly that which the masses could thoroughly appreciate [...]" (Henderson 1910, p. 404) and they were still reprinted and performed in the 1820s.

There was a market for "old traditional songs" and rural nostalgia, not at least because the Britons were experiencing massive economic and social changes while the country was developing from a basically rural, agrarian society to an urbanized and industrialized state. Performers and printers revived "real old songs" and classics like "Barbara Allen" (see f. ex. Johnson Ballads 266) or "The Gipsy Laddie" (see f. ex. Harding B25(731), at BBO) were reprinted on broadsides and performed for "Folk" of all kind. Professional songwriters were able to fulfill these demands, too. Rural songs were written in town and old ballads were created anew.

"Mary Of The Moor" is a product of these times, it was in no way originally a "Folksong" or a song from the countryside imported to London. Most likely it was the work of a London writer, a seasoned professional who knew what he wanted and what the people wished to hear and I doubt if it has ever seen any rural part of England before it was printed. Bob Dylan in his "Bob Dylan's Blues" (1963) mocked about "all the folk songs [...] written these days, up in Tin Pan Alley". It seems that "Mary Of The Wild Moor" is a Folksong written in 1820s London's "Tin Pan Alley".

VI. From Popular Song To Nostalgia Favourite

I have no idea what the intention of the author was when he wrote this song. Maybe it was originally a parody on "old Folk ballads", maybe he simply tried to cash in on the fad for old time music with a melodramatic tearjerker disguised as a folksong. It may have even been conceived as an ironic pastiche of moralizing fables á la "Winter's Evening". But the "folk" in the towns and on the countryside obviously loved it and I presume they didn't regard it as a "mawkish popular song" (Carl Sandburg).

"Mary Of The (Wild) Moor" remained popular for the several decades and was regularly reprinted. We know for example editions published in London by Pitts' successor Hodges (between 1844 and 1855, MB 05-3700), by H. Such (after 1848, Harding B 11(2364) at BBO), Fortey (between 1855 and 1885, MB 06-3985) and Disley (between 1860 and 1883, Firth b.25(147) at BBO). Provincial printers also offered the song to their customers. Some examples: Sefton in Worcester (Firth b.34(229), BBO) and Fordyce in Newcastle (MB 08-5425), both during the '30s; John Ross, also in Newcastle, in the late '30 or early '40s (MB 08-5663); Harkness in Preston (between 1835 and 1860, Harding B 11(4232), BBO); Barr in Leeds in the 1840s (Harding B 11(3), BBO, also Kidson Broadside Collection, FK/10/94/3 at The Full English). This broadside was also available in Ireland (see MB 12-8393, by the Bairds, Cork; Harding B 26(600), BBO, by Moore Belfast) and Scotland (2806 c.14(78), at BBO, McIntosh, Glasgow). By all accounts the song was in circulation on broadsides at least until the 1870s or even 1880s. But it is important to note that the British versions were never published with a tune, neither as sheet music or in a songbook. "Mary" remained confined to the "lower" stratum of popular music.

Like many other British songs "Mary Of The Wild Moor" migrated to North America where it became even more popular. In fact it was apparently one of the most popular songs of the second half of the 19th century. It is not possible to reconstruct the exact path of transmission. Country music historian Bill Malone notes that the song "came to America with professional British entertainers who toured the United States" (Singing Cowboys and Musical Mountaineers, p. 23). This is not an unreasonable assumption but I found no evidence for this claim. By all accounts it appeared first - with a slightly modified text - on a songsheet published in Boston in the 1830s (quoted from the catalog of the American Antiquarian Association):

- Mary, of the wild moor,: and the Waterman. Sold, wholesale and retail, by L. Deming, no. 62, Hanover St. Boston, and at Middlebury, Vt.[Mary of the wild moor; first line: One night the wind it blew cold. The Waterman, "as sung by Mr. Walton, at the Boston Theatre; " first line: Bound 'prentice to a waterman, I learn'd a bit to row.]

Mr. Deming was busy as a printer from 1829 until 1840 but published from this address only between 1832 and 1837 (see also Goldstein Collection, Broadside Publishers, [not available at the moment]). Interestingly here "Mary" was once again combined with "The Waterman" as on the above-mentioned broadside published by Catnach in London during the previous decade (see Copac) but it was not a reprint as can be seen from the modified opening line. The reference to "Mr. Walton" is intriguing but may lead on a false path. Thomas Walton was an English singer who came to Boston in 1827 where he sang at the Boston Theatre for some years before he moved on to Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York (see Wemyss, pp. 149-50, at Google Books). But it is clear from the text on the songsheet that he was only associated with "The Waterman" and there is no evidence that he was the one who introduced "Mary Of The Wild Moor" to American audiences. In fact the source for this modified text is not known. Was it derived from the performance of a singer? Who has edited the text? But it is not possible to answer these questions. The only thing we know is that during the 1830s the first American variant of the song became available.

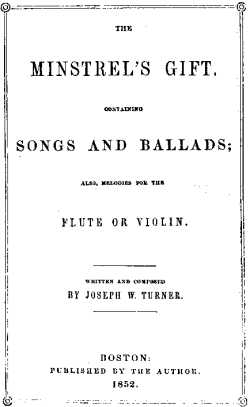

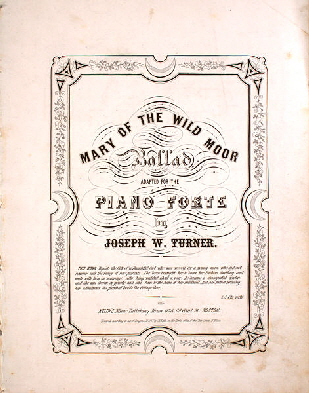

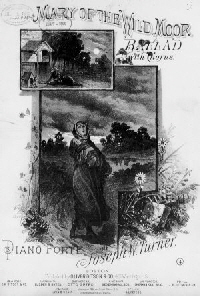

Much more important for the subsequent history of "Mary Of The Wild Moor" was a piano arrangement by composer Joseph W. Turner that was brought out by Keith's Music Publishing House in Boston in 1845 (available at the Levy  Sheet Music collection). This was the first time the song was published with music and thus aimed at a more "sophisticated" audience. Turner was a very popular and very busy American songwriter and arranger and just like his British colleague John Whitaker he is more or less forgotten today. I couldn't even find any biographical details about him. But more than 50 of his compositions since the mid-40s can be found in the sheet music collections of the Library Of Congress. In 1852 he published a book called The Minstrel's Gift, Containing Songs And Ballads; Also, Melodies For The Flute Or Violin including a collection of some his works and a list of the songs and instrumental pieces he had published so far (p. 120, available at Google Books). During the Civil War he seems to have been a supporter of Lincoln and the Union and in 1865 he wrote for example "A Nation Weeps: On The Death Of Abraham Lincoln" (available at Stern Collection, American Memory, LOC). Sheet Music collection). This was the first time the song was published with music and thus aimed at a more "sophisticated" audience. Turner was a very popular and very busy American songwriter and arranger and just like his British colleague John Whitaker he is more or less forgotten today. I couldn't even find any biographical details about him. But more than 50 of his compositions since the mid-40s can be found in the sheet music collections of the Library Of Congress. In 1852 he published a book called The Minstrel's Gift, Containing Songs And Ballads; Also, Melodies For The Flute Or Violin including a collection of some his works and a list of the songs and instrumental pieces he had published so far (p. 120, available at Google Books). During the Civil War he seems to have been a supporter of Lincoln and the Union and in 1865 he wrote for example "A Nation Weeps: On The Death Of Abraham Lincoln" (available at Stern Collection, American Memory, LOC).

The lyrics of this version leave the storyline intact. There are only some minor variations that don't look like improvements but make it sound even more stilted than the original British text:

One night when the wind it blew cold,

Blew bitter across the wild moor;

Young Mary she came with her child,

Wand'ring home to her own father's door;

Crying father, O pray let me in,

Take pity on me I implore,

Or the child at my bosom will die,

From the winds that blow 'cross the wild moor.

0, why did I leave this fair cot,

Where once I was happy and free;

Doom'd to roam without friends or a home,

0, father, take pity on me.

But her father was deaf to her cries,

Not a voice or a sound reach'd the door;

But the watch-dogs did bark, and the winds

Blew bitter across the wild moor.

0, how must her father have felt,

When he came to the door in the morn;

There he found Mary dead, and the child

Fondly clasped in its dead mother's arms.

While in frenzy he tore his gray hairs,

As on Mary he gazed at the door;

For that night she had perished and died,

From the winds that blew 'cross the wild moor.

The father in grief pined away,

The child to the grave was soon borne;

And no one lives there to this day,

For the cottage to ruin has gone.

The villagers point out the spot

Where a willow droops over the door;

Saying, there Mary perished and died,

From the winds that blew 'cross the wild moor.

There is a note on the cover of the sheet music that explains why Mary had to return home and even reinstates the motif of the cruel father who doesn't let her into the house:

"This song depicts the fate of a beautiful girl who was wooed by a young man who did not however suit the fancy of her parents. The lover besought her to leave her father's dwelling and unite with him in marriage. After being wedded about a year, he became a dissipated wretch, and she was driven by poverty and [cold?] back to the home of her childhood. But her father refusing her admittance she perished beside the cottage door"

Maybe Turner or his publisher made it up themselves because the song was lacking any information about what had happened to the girl before she tried to make it back to her father and their "fair cot" and Turner had even deleted the line where Mary was described as the former "village pride".

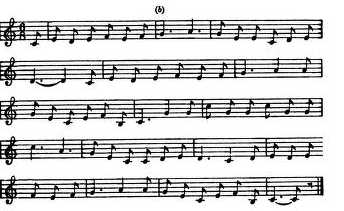

Turner is only credited as the arranger of this version of "Mary Of The Wild Moor". According to Helen K. Johnson in Our Familiar Songs (1889, p. 303) he had combined the lyrics with another melody that "had never been linked" to this song until he "united them, added a few lines, and adapted them with a piano arrangement". But in fact his tune it is not so different from the one Whitaker had written for "The Robin's Petition". Here is the melody used by Turner. The original key is Eb and I have transposed it to D:

Another look at the Whitaker's melody shows that Turner has retained some parts of the original, especially the simple but effective melodic motif in the fifth bar:

It's easy to see that Turner's melody is only a variant of Whitaker's. He must have seen a performance of the British version of "Mary Of The Wild Moor" because that song had up to that point never been published with music but only on broadsides. It would be interesting to know if Turner himself was responsible for the variations or if he had heard it that way.

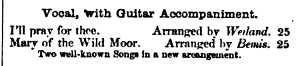

Turner's arrangement was apparently immensely popular during the next decades. An interesting version for guitar players was included in a book called Guitar Without A Master (pp. 52-3, Ditson, Boston, n. d., ca. 1851 according the the catalog of the LOC). "Mary Of The Wild Moor" with guitar accompaniment was also published as sheet music by Ditson in 1858 (see  Dwight's Journal of Music, 14.8.1858, p. 160, at Google Books) but I can't say if it was the piece from that book. The text can also be found in songsters, cheap, Dwight's Journal of Music, 14.8.1858, p. 160, at Google Books) but I can't say if it was the piece from that book. The text can also be found in songsters, cheap, pocket-sized books with only the lyrics but not the music of popular and traditional songs well known among the people. One example is The Shilling Song Book. A Collection Of 175 Of The Most Favorite National, Patriotic, Sentimental, And Comic Ballads Of The Day (W. E. Tunis, Niagara Falls 1860, p. 41, at Google Books). Turner's version was even exported back to Britain and published as sheet music in Leeds in 1872 (see Copac). This was in fact the very first time the song was available with music in England and thus brought to the attention of more educated music lovers. pocket-sized books with only the lyrics but not the music of popular and traditional songs well known among the people. One example is The Shilling Song Book. A Collection Of 175 Of The Most Favorite National, Patriotic, Sentimental, And Comic Ballads Of The Day (W. E. Tunis, Niagara Falls 1860, p. 41, at Google Books). Turner's version was even exported back to Britain and published as sheet music in Leeds in 1872 (see Copac). This was in fact the very first time the song was available with music in England and thus brought to the attention of more educated music lovers.

Another American variant with a different set of revisions was published first on a couple of songsheets in the 1850s. It's not Turner's text and I don't think it was derived from his version. This adaption seems to be based on an original British broadside. It is not known which melody was used for this variant nor who the reviser was. Maybe it was an editor at the publisher's office or a performer who used to sing it on stage. One gets the impression that the reviser tried to modernize the lyrics a little bit and repair some inconsistencies of the original. Mary is now described as a former "gay village bride" and the tolling of the village bells may be a nod to the death bells in "Barbara Allen".

It was on one cold winters night,

As the wind blew across the wild moor,

When Mary came wandering home with her babe,

'Till she came to her own father's door;

"Oh father, dear father" she cried,

"Come down and open the door,

Or the child in my arms will perish and die,

By the wind that blows across the wild moor.

Oh why did I leave this dear spot,

Where once I was happy and free,

But now doomed to roam without friends or home,

And no one to take pity on me."

The old man was deaf to her cries,

Not a sound of her voice reached his ear,

But the watch dog did howl and the village bell toll'd,

And the wind blew across the wild moor.

But how must the old man have felt,

When he came to the door in the morn,--

Poor Mary was dead but the child was alive,

Closely pressed in its dead mother's arms;

Half frantic he tore his gray hair,

And the tears down his cheeks they did pour;

Saying "this cold winters night, she perished and died

By the wind that blew across the wild moor.

The old man in grief pined away,

And the child to its mother went soon,

And no one, they say, has lived there to this day,

And the cottage to ruin has gone;

The villagers point out the spot,

Where the willow droops over the door,

Saying there Mary died, once a gay village bride,

'By the winds that blew across the wild moor.

This is from a songsheet published in New York by "Andrews', Printer, 38 Chatham St." (available at the Goldstein Collection, 000090-BROAD). John Andrews worked at this address between 1853 and 1858 (see Charosh, p. 469). We can find this text also on a broadside printed by A. W. Auner from Philadelphia in 1853/4 (see the catalog of the New York Historical Society). I don't know who was the first to publish this set of lyrics but it is safe to assume that it was available at least since the first half of the 1850s. This variant was also regularly reprinted and remained on the market for considerable time. For example New York publisher Beadle included the lyrics to "Mary" four times in his popular songsters, more often than a lot of other songs (see Johannsen). They could be found in the Dime Songbook No. 2 (1859, p. 28), the Songbook For The People (1865), the Pocket Songster No. 4 (1866) and in the Half Dime Singer's Library No. 3 (1878). This is from a songsheet published in New York by "Andrews', Printer, 38 Chatham St." (available at the Goldstein Collection, 000090-BROAD). John Andrews worked at this address between 1853 and 1858 (see Charosh, p. 469). We can find this text also on a broadside printed by A. W. Auner from Philadelphia in 1853/4 (see the catalog of the New York Historical Society). I don't know who was the first to publish this set of lyrics but it is safe to assume that it was available at least since the first half of the 1850s. This variant was also regularly reprinted and remained on the market for considerable time. For example New York publisher Beadle included the lyrics to "Mary" four times in his popular songsters, more often than a lot of other songs (see Johannsen). They could be found in the Dime Songbook No. 2 (1859, p. 28), the Songbook For The People (1865), the Pocket Songster No. 4 (1866) and in the Half Dime Singer's Library No. 3 (1878).

Other broadside printers also didn't hesitate to recycle this popular piece. J. H. Johnson in Philadelphia published a couple of editions since the late '50s (see f. ex. Levy Collection). The copy in the library of the American Antiquarian Society even has an additional note: "By sending Johnson 35 cts., he will send you the music for this song." (see Catalog, AAS). Unfortunately it is not known which tune he offered here to his customers. Other copies of the text were for example printed by Horace Partridge in Boston "between 1860 and 1870", see the entry in the catalog of New York Historical Society), Thomas G. Doyle in Baltimore (see America Singing, LOC) and de Marsan - Andrews' successor - in New York (see America Singing, LOC, between 1861 and 1864, see Charosh, p. 469).

These song sheets were sold in great numbers in shops and on the streets all over the country. The fact that this  version of "Mary" was available from printers in different towns is a sign for the song's consistent popularity. F. G. Fairfield, researching popular songs in New York in 1870, found "Mary Of The Wild Moor" still among the sheets offered by sellers on the streets : version of "Mary" was available from printers in different towns is a sign for the song's consistent popularity. F. G. Fairfield, researching popular songs in New York in 1870, found "Mary Of The Wild Moor" still among the sheets offered by sellers on the streets :

"The vendor is often a ragged urchin, but sometimes we find a young girl patiently displaying and offering her wares. Scan the titles closely, and you will meet here and there the face of an old acquaintance-" Mary of the Wild Moor," perhaps, or Watson's pathetic little ballad, "And she sent as she went Sunshine to and fro." If you happen to be familiar with London -street and concert-hall ballads, you will stumble over many a scrap you have heard before-for not less than one-third of the whole collection is of transatlantic origin" (quoted from Fairfield, Appleton's Journal 3, 1870, pp. 68-70, available at Making of America, Journal Articles & The Internet Archive).

At this point "Mary Of The Wild Moor" was a song popular from the parlors to the streets and it was known all over North America, both in urban and rural areas. There are even a couple of interesting sources available where we can learn a little bit about the performance context. For example Adolphus Gaetz from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia reports in his diary about a concert on January 1st, 1856 with 350 people in attendance where "Mary" was part of the program (Ferguson 1965, pp. 22-3, online available at Simon Fraser University Library, Digital Collections):

|

|

|

Tuesday, 1st, - This year commenced with a mild day. This evening the Concert, got up for Miss Jane Bolman (the blind Girl), went off exceedingly well. Doors were open at 7 O'clock, but long before that time the Street leading to the 'Temperance Hall", was thronged with people; it became necessary therefore to open the doors before the time appointed. Upwards of 350 persons were congregated in the Hall [...] The performers were, -

W. B. Lawson, bass singer.

Jasper Metzler, do.

Wm. Townshind, Clarionett.

A. Gaetz, do.

James Dowling, Bass Viol.

Wm. Smith, do., & bass singer

Miss Jane Bolman, piano Forte, & Guitar

Miss Cossman, piano Forte.

[...]

The following pieces were performed: -

1. Anthem from luke 2 chap. There were shepherds, etc

2. He doeth all things well. Solo by Miss Bolman.

3. Sanctus, by Fallon.

4. Mortals Awake, (christmas piece)

5. The little Sghroud. Solo by Miss Bolman.

6. Haec Dies, by Webbe.

7. Great is the lord.

Part 2nd.

1. Home, sweet Home, with Variations, piano solo by Miss Bolman.

2. The mountain Maid's Invitation.

3. Billy Grimes, Guitar accompaniment by Miss Bolman

4. Lilly Bell

5. The welcome me again, by Miss Bolman.

6. Mary Of The Wild Moor.

7. Give me a cot. Solo by Miss Bolman.

8. The Grave of Napoleon.

9. The little Maid. Guitar accompaniment by Miss Bolman.

10. God save the Queen.

|

|

|

This looks like a typical local concert with mostly amateur performers. The first part of the program consisted of religious pieces while the second part offered popular songs of that time. Unfortunately it is not known which version of "Mary" was performed here: the English original or one of the American variants.

According to A. N. Somers' History of Lancaster, New Hampshire - published in 1899 - "Mary Of The Wild Moor" was amongst the songs performed at corn huskings "half a century ago" (pp. 358f):

[...] singing was always in order . There were well-known and popular singers in each community whose presence was much sought on these occasions, and who prided themselves upon their accomplishments and their popularity [...] A strong voice and a collection of popular songs were the chief requisites [...] a favorite was the ballad of 'Mary of the Wild Moor'" (pp. 359, 362).

The same was reported from Massachusetts (see Butterworth 1895, p. 235). The song can also be found in the so-called Steven-Douglass Manuscript from Western New York. The pieces collected here were mostly part of the repertoire of a local singer by the name of Artemas Stevens and according to the editor they "were used in social gatherings from 1840-1860 or later" (see Thompson 1958, pp. ix-x & 184-6). Stuart Frank (2010, pp. 236-7) found the the text of "Mary" - "evidently copied from printed sources" - in two notebooks of American sailors from the late 1860s. In all these cases the lyrics quoted are clearly derived from Turner's sheet music and not from the later songsheet version.

Both American variants of "Mary Of The Wild Moor" remained on the popular music  market until the turn of the century and beyond. The text from the songsheet was reprinted for example by Schmidt in Baltimore (see Goldstein Collection, 002278-BROAD) and Wehman in New York (dto, 001940-BROAD) during the '80s.It also appeared in songsters like Song And Joke Book No. 3 by the Wehman Bros. (ca. 1900, [p. 7], available at the Internet Archive). Turner's "Mary" was even published in a new edition by Ditson in Boston in 1882 (available at Music for the Nation: American Sheet Music, LOC), this time with much more vivid illustrations on the cover. Strangely the original piano arrangement of the original version was replaced by a new one although I can't say if it was really written by Mr. Turner. At least he is still credited on the cover. Additionally a new chorus for a vocal quartet has been included. Interestingly the copyright for this piece was renewed in 1910 (see Catalog of Copyright Entries, 1910, 17742 (17), p. 1016) and as late as 1913 it was still listed in Ditson's Catalog of Vocal Music (p. 113). In the introduction the publisher notes that this catalog "includes only the issues of earlier years that have stood the test of time and proved their permanence" (p. 3). market until the turn of the century and beyond. The text from the songsheet was reprinted for example by Schmidt in Baltimore (see Goldstein Collection, 002278-BROAD) and Wehman in New York (dto, 001940-BROAD) during the '80s.It also appeared in songsters like Song And Joke Book No. 3 by the Wehman Bros. (ca. 1900, [p. 7], available at the Internet Archive). Turner's "Mary" was even published in a new edition by Ditson in Boston in 1882 (available at Music for the Nation: American Sheet Music, LOC), this time with much more vivid illustrations on the cover. Strangely the original piano arrangement of the original version was replaced by a new one although I can't say if it was really written by Mr. Turner. At least he is still credited on the cover. Additionally a new chorus for a vocal quartet has been included. Interestingly the copyright for this piece was renewed in 1910 (see Catalog of Copyright Entries, 1910, 17742 (17), p. 1016) and as late as 1913 it was still listed in Ditson's Catalog of Vocal Music (p. 113). In the introduction the publisher notes that this catalog "includes only the issues of earlier years that have stood the test of time and proved their permanence" (p. 3).

But during these years "Mary Of The Wild Moor" also mutated into something different. It was not only a simple popular song but became an "old ballad". Already in 1874 this designation was used when the text from Turner's version was reprinted - together with a romantic illustration by one John N. Davies - in The Aldine, an ambitious art journal for sophisticated readers (Vol. 7, Nr. 12, p. 234, available at jstor & The Internet Archive).

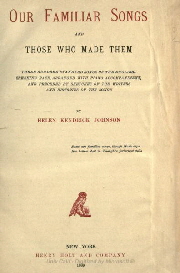

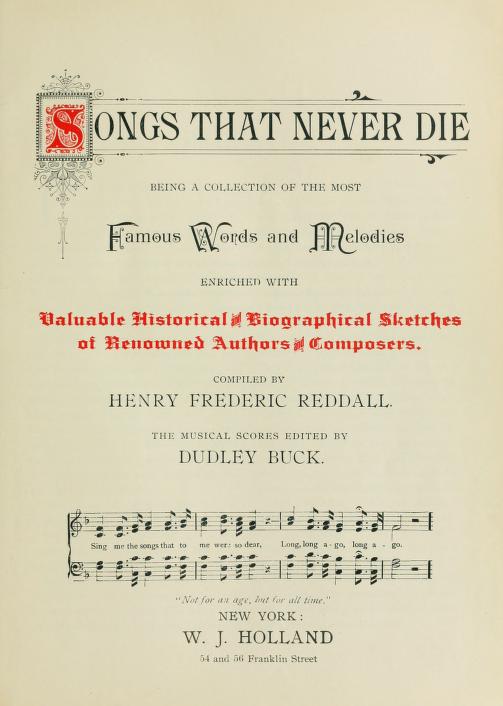

In 1889 Helen K. Johnson included Turner's "Mary" in her influential Our Familiar Songs (p. 303). Here she used the original piano arrangement from the original edition of the sheet music. She even claimed that words and music were "very old", something that surely would have pleased and amused the anonymous writer from circa 65 years ago.  Interestingly she also noted that the "song is so poor as poetry, that it has depended for its popularity solely upon the plaintive beauty of" the melody. I have some doubts about that and I don't think only Turner's music was important. This judgment seems to be more a reflection of her highbrow tastes. Ms. Johnson's book deserves special note as it was an impressive compendium, nearly a canon of the most popular songs of the 19th century of British origin, "Three Hundred Standard Songs of The English Speaking Race, Arranged With Piano Accompaniment, And Preceded By Sketches Of The Writers And The Histories Of The Songs". She had caught them at a moment when they were in the process of being transformed from current popular songs to old favorites of nostalgic value: "They need no introduction; they come with a latch-string assurance of old and valued friends [...] They are not popular songs merely, nor old songs exclusively, but well-known songs, of various times [...] " (p. v). Interestingly she also noted that the "song is so poor as poetry, that it has depended for its popularity solely upon the plaintive beauty of" the melody. I have some doubts about that and I don't think only Turner's music was important. This judgment seems to be more a reflection of her highbrow tastes. Ms. Johnson's book deserves special note as it was an impressive compendium, nearly a canon of the most popular songs of the 19th century of British origin, "Three Hundred Standard Songs of The English Speaking Race, Arranged With Piano Accompaniment, And Preceded By Sketches Of The Writers And The Histories Of The Songs". She had caught them at a moment when they were in the process of being transformed from current popular songs to old favorites of nostalgic value: "They need no introduction; they come with a latch-string assurance of old and valued friends [...] They are not popular songs merely, nor old songs exclusively, but well-known songs, of various times [...] " (p. v).